by Justin Davies[1]

Introduction

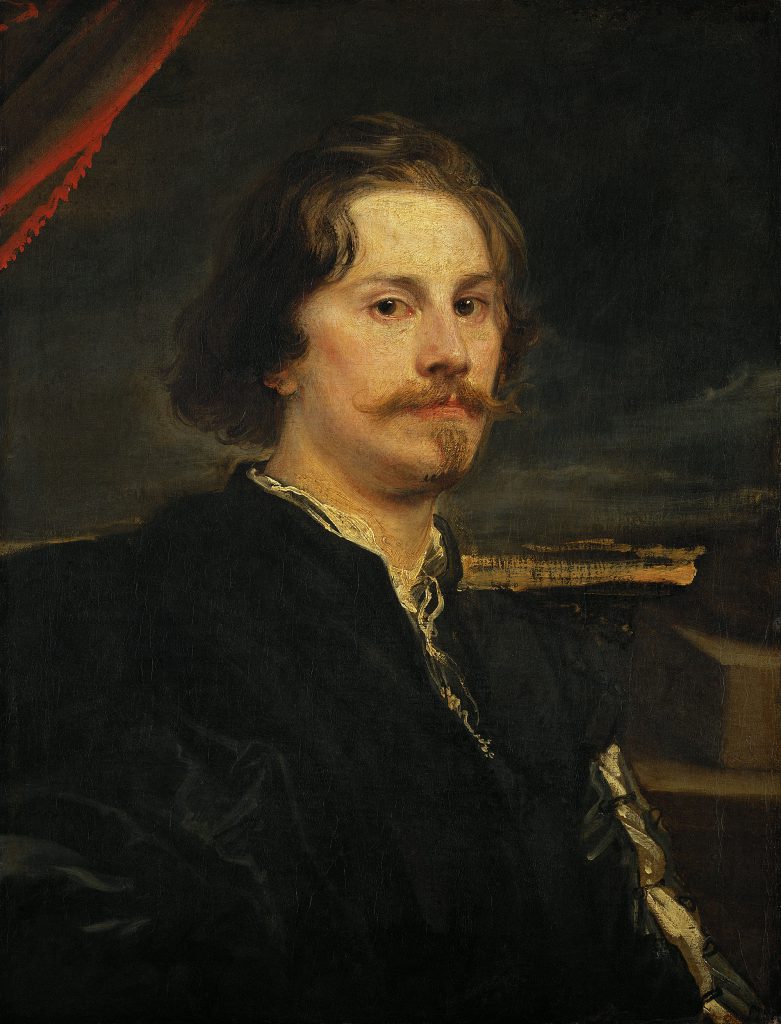

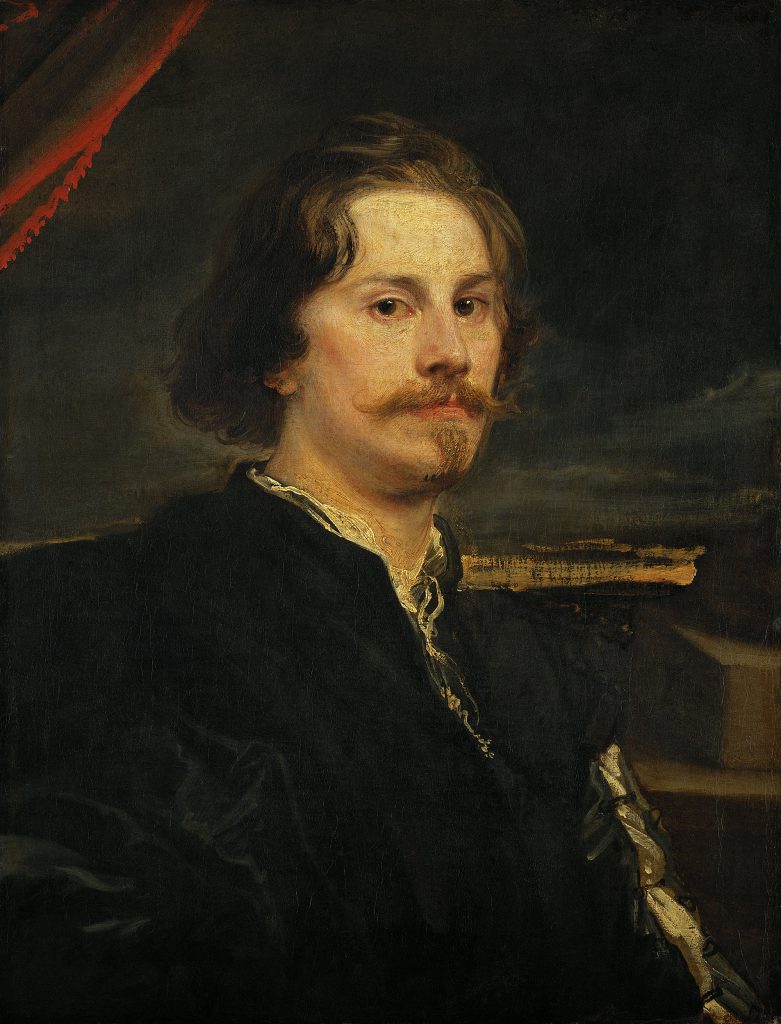

Portraiture remains the most popular and best studied part of Anthony Van Dyck’s oeuvre. Despite the fame of the artist, his paintings and many of his sitters, some of his subjects still evade identification or their identification was recorded centuries ago and then lost. This is the case with Van Dyck’s vivid ‘portrait of a man’ in the Kunsthistorisches Museum (fig. 1), the identification of which is the focus of this study. Following a recent re-examination of primary sources and a new archival discovery, it is proposed that the unidentified man has now been identified. And that Van Dyck’s handsome model is the Dutch Golden Age painter and engraver Pieter Soutman (1593/1601-1657).

The picture

The painting (fig. 1), oil on canvas, 75.5 x 58 cm, depicts the head and shoulders of a young man with slightly shorter than shoulder-length hair, moustaches and a tuft of beard on the chin, next to a partial column on one side and a curtain on the other. It is painted with great confidence and an economy of means that is so typical of Van Dyck’s autograph works. Strokes of rapidly painted impasto conjure up the curtain (fig. 2), collar (fig. 3) and sleeve (fig. 4). The imprimatura on the canvas is visible on the sleeve. Van Dyck used it as part of the clothing, as he had done with paintings on panel in his first Antwerp period up to 1621.[2]

The painting has been cut down. The original format might possibly be reflected in a more finished three-quarter version of the portrait in the Louvre, with which it has been associated (fig. 5).[3] There, the subject stands beside a column with a curtain behind him. His right hand rests elegantly on his hip and the other on the hilt of a sword. The Louvre painting is more finished than that of Vienna and contains differences throughout. Further research is required to determine the exact relation between the two.

The provenance of the Vienna painting

A Van Dyck portrait of a man, called ‘long Peter’, the King of Poland’s painter, in a black mantle with blue sleeves, the right hand on his sword, is listed in the inventory of the Archduke Leopold-Wilhelm (1614-1662) compiled in 1659:

Ein Contrafait von Öhlfarb auf Leinwaeth des langen Peter, Könings in Pohlen Mahlers, in einem schwartzen Klaidt vnndt Mantel mit bläwen Ärmblen vnd hatt die rechte Handt auff seinem Degel; In einer Schwartz ebenen Ramen, das innere Leistel verguldt, 7 Spann 4 Finger hoch vnndt 6 Spann braith. Original von Anthonio von Deyckh.[4]

It should be noted that it is the right hand, rather than the left as in the Louvre painting, which is described as being on the sword. This may be how the compiler viewed the painting rather than referring to the hand of the subject. The description also mentions blue on the sleeves. Whilst the Vienna painting has been cut down and the remaining canvas does not contain blue, the Louvre version shows the subject with blue cuffs, though the smalt has faded somewhat. ‘7 Spann 4 Finger hoch vnndt 6 Spann braith’ equates to 153.9 x 124.8 cm. Taking a sturdy frame into consideration in these measurements, the original measurements of the Vienna painting may have been close to the Louvre version, 113.7 x 92 cm.

The collection of the art loving Archduke, governor of the Spanish Netherlands (1648-1656), returned with him to Vienna in 1656. He had added significantly to his collection while living in Brussels, notably through the acquisitions made by his court painter and curator, David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690), from 1651 onwards. Leopold-Wilhelm’s collection was inherited in 1662 by his nephew, the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I (1640-1705).

Previous identifications

The possible identification as a self-portrait of Van Dyck was rejected in 1884 by Eduard von Engerth, director of the Belvedere Gallery.[5] In 1931, the director of the Gemäldegalerie of Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gustav Glück, proposed the animal painter Paul de Vos (1590-1678), on the basis of a perceived likeness to an engraving by Van Dyck (fig. 6).[6]

More recently, since 1998, the painter Jan Boeckhorst (1604-1688) has been proposed.[7] On the reverse of a drawing in the Stadelmuseum Münster of the head in the Vienna and Louvre paintings, is a label, written after 1662 when Emperor Leopold had inherited Archduke Leopold –Wilhelm’s collection, which reads:

“A. v. dipenbeke deliniavit secundum A. V. Dyck/effigies Joannes Bouchorst Lange ian apellatus Leop. I imp habet originale/Rome doctor faustus apellatus.”[8]

Which can be translated as:

“Drawn by Abraham Van Diepenbeeck (1596-1675) after Anthony Van Dyck/likeness of Jan Boeckhorst called ‘Lange Jan’, Leopold I has the original/he was called Doctor Faustus in Rome.”

In the 2004 Van Dyck. A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, Nora de Poorter rejected both identifications. Paul de Vos was rejected owing to the lack of similarity between the engraving and the painted portrait. Jan Boeckhorst because the painting was placed in Van Dyck’s first Antwerp period (up to 1621) in the 2004 catalogue. Boeckhorst was born in 1604 and did not move from Münster to Antwerp until 1626. In addition, it was noted that a sword was an unlikely attribute for a painter and ‘an even more unlikely attribute for Boeckhorst, who as a canon with prebends, was an (unordained) clergyman.’[9] Comparative portraits of Boeckhorst do not exist.

If the Louvre portrait ever possessed a contemporary identification it was lost when its last owner, Catherine Françoise Charlotte de Cossé-Brissac, the widowed Duchesse de Noailles (1724-1794), was guillotined during the ‘Terror’, aged 70. The painting was subsequently seized by the French state, her son having understandably fled France.[10]

The date of the painting

The painting is undated. The 2004 Van Dyck catalogue placed it in the first Antwerp period (up to October 1621) but Nora de Poorter noted that, ‘The disfigurement of this Italianising portrait complicates its evaluation. Both the medium-length hair and the costume with the ‘open’ sleeves argue for a dating after 1621. Cust [1900] and Schaeffer [1909], moreover, situated the work in the Italian period (1621-7).’[11]

The proposal – Pieter Soutman (1593/1601-1657) painted in 1628

Archduke Leopold-Wilhelm’s 1659 inventory lists the painting as portraying ‘long Peter, the King of Poland’s painter.’ Pieter Soutman, born in Haarlem between 1593 and 1601 according to his most recent biographers, became the painter to the King of Poland Sigismund III Vasa (1587-1632) around 1624.[12] He is thought to have lived in Warsaw from 1624 to 1628 before returning to Haarlem, where he was a successful painter and engraver until he died in 1657.[13]

Although he was based in Haarlem, he continued to paint for the Kings of Poland, first Sigismund, then after his death in 1632, his son King Ladislaus IV Vasa (1595-1648). He painted a portrait of King Ladislaus in 1643.[14] In the letter below, dated 8 February 1645, to the art dealer Matthijs Musson in Antwerp, Soutman styles himself, ‘Pittore di Sua maesta de Polonia’ – Painter to his Majesty the King of Poland’.

This letter also reveals the existence of a portrait of Soutman by Van Dyck. At the time of writing, Soutman was trying to sell four Van Dyck’s he owned to a client of Musson, the Canon of Antwerp Cathedral, Antonio Tassis:

Mr. Musson

…

The Van Dyck portrait of me is estimated as high as anyone has seen anything by Van Dyck. It will not leave my hands, even for 300 guilders in cash. This, my dear friend, is for the sweet story. And if by chance [the sale of the four paintings] goes through thanks to the bringer of this letter, be amicably greeted with your entire family and recommended to the grace of almighty God.

Your obedient and very devoted friend,

Petr Soutman, Pittore di Sua maesta de Polonia (Painter to His majesty the King of Poland)

Harlem, 8 February 1645[15]

The sale evidently fell through as a newly discovered and previously unpublished letter reveals that Soutman sold his portrait by Van Dyck to Archduke Leopold-Wilhelm six years later. In this letter to Musson dated April 1651, Soutman wrote:

Mr. Musson,

…

I would have visited you already, were it not that recently my father-in-law passed away and my love gave birth to a daughter at Easter, if my situation permits I’ll be with you in 2 or 3 weeks, if you have received money in the meantime, please keep it at yours up till my arrival. I will apparently talk with His Highness, because that my portrait is there has its reason. And if payment is not available by then, I will ask His Highness about this personally, this Dear Friend is at your discretion, And recommend myself that I may remain your humble eternal servant

P.S.

In April, Haarlem 1651[16]

The reason why the painting was sold is lost. Archduke Leopold-Wilhelm would have known Soutman’s paintings. Soutman’s portraits of Leopold-Wilhelm’s Polish relations, including the 1643 portrait of King Ladislas mentioned above, hung in the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels where he lived.[17]

Corroboration that the portrait was sold to Archduke Leopold-Wilhelm can be found in Musson’s daybook for February 1651. It records that 100 guilders were received for Soutman from David Teniers, the Archduke’s curator in Brussels. It is not known why Soutman accepted 200 guilders less than the value he had placed on the portrait in 1644 but it may be linked to the unknown reason for the sale referred to above.

Paid to Mr Adriaasen on 4 February 1651 in de Peter Pot Street the

amount of Guilders (Fl) 78-19 (stuyvers)[18]

As a promise of 3 stuyvers in coins, on the account of Mr. Peeter

Soutmans in Haarlem and he owes me 9 and a half prints at 48

stuyvers a piece Guilders (Fl) 22-16 (stuyvers)

Deduced in current money makes together 101 guilders 15 stuyvers

which I received on behalf of Mr. Peeter Soutmans from Mr. David

Teniers in Brussels 100 guilders as promise 3 stuyvers in coins.[19]

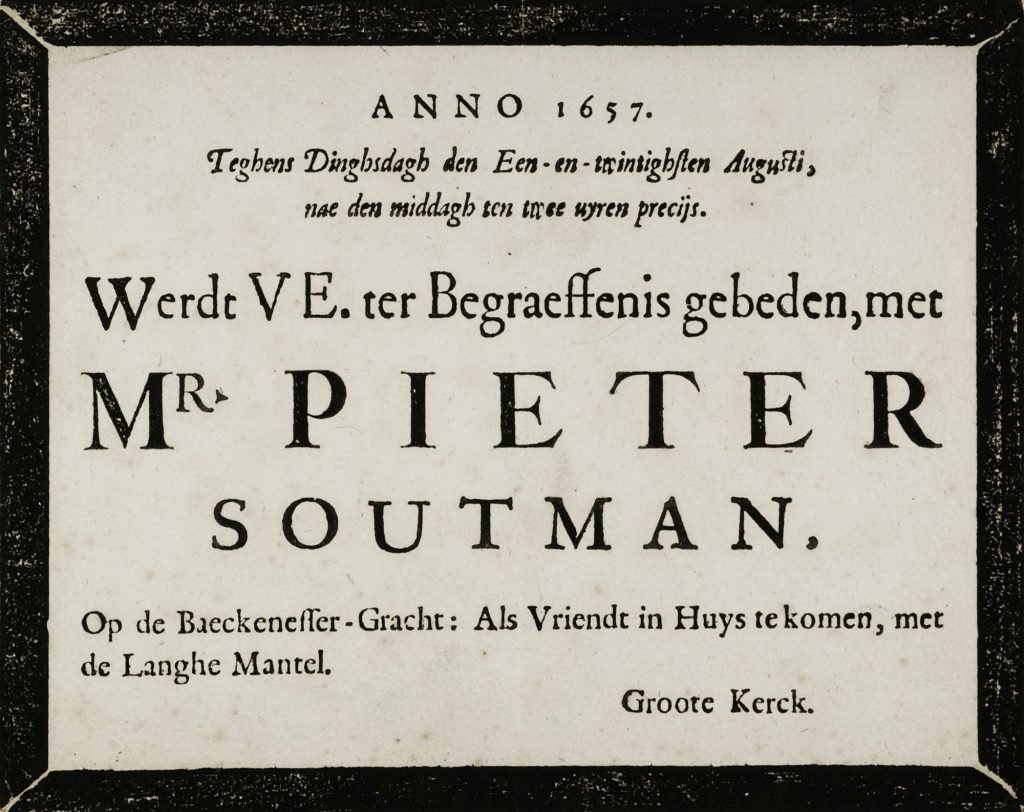

Contemporary archival sources mentioning Pieter Soutman, apart from those involving formal legal business, are sadly lacking. Therefore, it has not been possible to find references to his being called by the nickname ‘Langhen Peter’. The only intimation of his height linked nickname is that his house in Haarlem in which he died in 1657 was called ‘de langhe Mantel’ – the long cloak (fig. 7).[20]

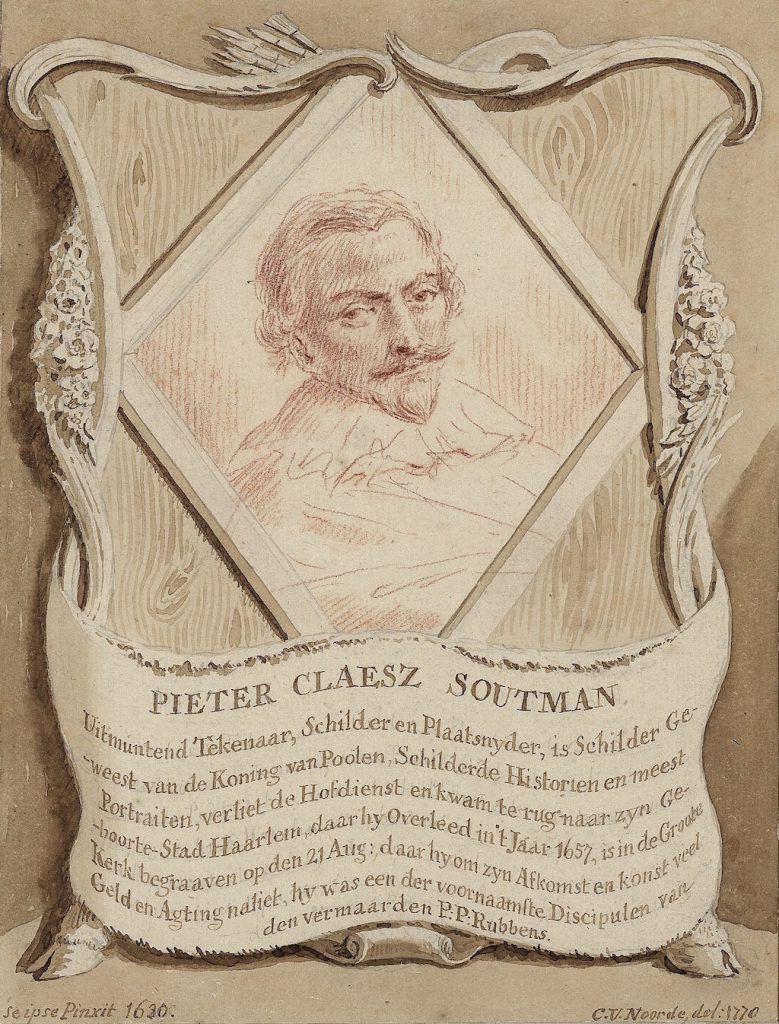

Corroborated, comparative images of Pieter Soutman are also lacking. He does not feature in the engraved portraits known as Van Dyck’s Iconography, neither in Jan Meyssens’ Image de divers hommes d’esprit sublime, Antwerp, 1649, nor Cornelis de Bie’s Het Gulden Cabinet vande edele vry Schilder-Const, 1662. In the Haarlem Noord-Holland Archives, there is a 1770 drawing by Cornelis van Noorde (1731-1795), with a legend that purports that it is a copy from an unknown Soutman self-portrait of 1630 (fig. 8).[21] It shows an elegant, thinner-faced man, looking older than Soutman would have been in 1630. The one hundred and forty years’ time lapse renders the likeness unreliable.

As noted above, art historians have placed the Vienna painting in both Van Dyck’s first Antwerp (up to October 1621) and Italian (1621-7) periods. Soutman and Van Dyck certainly knew each other before Van Dyck’s departure for Italy in October 1621, as they both worked together for Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) from around 1616.[22] Rubens’s nephew Philip (1611-1678) mentioned them together in his memoir of his uncle, Vita Petri Pauli Rubenii:

‘In arte pictoriâ plurimos habuit discipulos, inter quos excellerunt Petrus Soutmans, pictor Sigismundi, regis Poloniæ, Justus van Egmond, Erasmus Quellinus, Joannes Brouchorst, Joannes vanden Hoecke, pictor archiducis Leopoldi, et præcipuè Antonius van Dyck, cujus ingenium advertens, eum in familiam recepit, et unicum alumnum habuit, qui talem progressum fecit, ut in eâ arte nemini cesserit.’[23]

‘In the art of painting he had many pupils, among whom excelled Peter Soutmans, the painter of Sigismund, King of Poland, Justus van Egmond, Erasmus Quellinus, Johannes Brouchorst, Johannes van den Hoecke, painter of the Archduke Leopold, and especially Anthony Van Dyck, whose talent Rubens recognised. He (Rubens) received Van Dyck into his household and regarded him as a unique pupil; the latter (Van Dyke) made such progress in his art that he yielded first place to no one.’[24]

As noted previously, Nora de Poorter wrote that the sword is an unusual attribute for a painter. It raises the question as to whether Soutman was portrayed with a sword to signify that he was a member of a royal court as the painter to a King? While certainly unusual in portraits of artists (royally gifted gold chains are more prevalent), it would not be unique. A portrait of Deodate Del Mont, the court painter to the Duke of Neuberg and later the Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella in the Spanish Netherlands, engraved by Lucas Vorsterman after Van Dyck, shows him with both a sword and chain (fig. 9).

In which case, Soutman’s portrait may date from 1624, when he was appointed the King of Poland’s painter, or after. Nora de Poorter also noted that the clothes and hairstyle indicate a date for the painting after 1621. King Sigismund’s son, Prince Ladislas, visited Antwerp and Rubens’s studio in September 1624, where he met Soutman. He returned to Brussels and left for a tour of Italy.[25] Did Soutman accompany Ladislas to Italy and did they encounter Van Dyck?

Ladislas’s itinerary incorporated Milan, Genoa, Pisa, Parma, Bologna, Loreto, Assisi and Rome in November and December 1624. From Rome in January 1625 he proceeded to Naples, Siena, Florence, back to Bologna, Mantua, Padua and Venice, before appearing in Villach in March 1625 and wending his way back to Warsaw.[26]

Van Dyck was in Sicily throughout this time. He had arrived in Palermo in the spring of 1624 and was soon embroiled in a virulent outbreak of the plague. Previously, it had been thought that Van Dyck might have escaped back to the mainland to avoid its worst but it now appears that he remained on the island until September 1625.[27] Even if Soutman had accompanied Ladislas to Italy, it appears unlikely that he would have met Van Dyck. In which case, the portrait could not have been painted in Italy.

There is a strong possibility that Soutman and Van Dyck met in the Spanish Netherlands in 1628. Soutman left Antwerp around 1624 and lived in Haarlem from 1628 until his death. On 22 November 1628, he was granted a passport to travel to Brussels to deliver three portraits painted by him, gifted by the King of Poland to the Archduchess Isabella:[28]

‘To all our Clerks, we have given and give by this leave and license to Peter Soutermans to travel from the Provinces of Holland to those of ours, with a case of paintings coming from Poland for us. We order and command on behalf of Her Majesty to allow him and the said case to go freely, travel and return, without hindrance, for the duration of this passport … months. Done in Brussels, under our name and secret seal, the twentieth of November, 1628.’[29]

Van Dyck returned from Italy in 1627. He could certainly have met Soutman at this time, either in Antwerp or Brussels. In April 1628, he had received a large commission to paint the Brussels City Council.[30]

Conclusion

The 1659 inventory identifies a portrait in Archduke Leopold-Wilhelm’s collection as that of the painter of the King of Poland called Peter. This was the title used by Pieter Soutman from 1624 until at least 1645, if not until the end of his life in 1657. Both he and Van Dyck were in the Spanish Netherlands in 1628, at the start of Van Dyck’s second Antwerp period. The painting has previously bounced between the first Antwerp and Italian periods and a 1628 date would account for its vivid painting style and the post-1621 clothing. It is a rapidly executed portrait, which appears almost unfinished. It is not a finely rendered formal commission but perhaps a portrait for a friend. It is recorded that Pieter Soutman had known Van Dyck well for more than 10 years by 1628 and that he owned a portrait by him. And now known that the portrait was sold in 1651 to Archduke Leopold-Wilhem. Therefore, there is compelling evidence to identify Van Dyck’s striking portrait in Vienna as that of the Dutch Golden Age painter, Pieter Soutman from Haarlem.

[1] Co-founder, coordination and research fellow, Jordaens & Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project www.jordaensvandyck.org. I would like to thank Gerlinde Gruber, Karin Zeleny, Joost Vander Auwera, Blaise Ducos, Jeremy Wood and Michael Lomax for their kind assistance with this article, also JVDPPP Archival Research Fellow Piet Bakker for his discovery of the 1651 Soutman to Musson letter and its translation. This text was first published in German, in Ansichtssache 20, Ein Maler also Modell: Van Dycks Porträt von Pieter Soutman, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March 2018 (available through this link)

[2] An example of this can be seen on the Portrait of a Man Drawing on his Glove, oil on panel, 107 x 74 cm, Gemâldegalerie Alte Meister der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen, Dresden, inv. no. 1023 C.

[3] Jacques Foucart, Catalogue des peintures flamandes et hollandaises du musée du Louvre, Paris, 2009, p. 132.

[4] A. Berger, ‘Inventar der Kunstsammlung des Erzherzogs Leopold Wilhelm von Österreich’, Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Ah. Kaisershaus, Bd. 1, Wien, 1883, p. CXLIX, no. 722. The 1659 manuscript original is housed in the Fürstlich Schwarzenberg’sche Familienstiftung Vaduz, Murau. The connection between the painting under discussion and Leopold-Wilhelm’s inventory was first made and published by Clara Garas in 1968. Clara Garas, ‘Das Schicksal der Sammlung des Erzherzogs Leopold Wilhelm.’, Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien, Wien LXIV. NF XXVIII 1968, pp. 181-278. p. 62 ill., p. 268.

[5] Eduard von Engerth, Kunsthistorische Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, Gemälde, Beschreibendes Verzeichnis, vol. 2, 1884, Vienna, 1892, p. 124.

[6] Gustav Glück, Van Dyck, des Meisters Gemälde, Klassiker der Kunst, no. 13, 2nd rev. ed, Stuttgart, 1931, p. 123-left.

[7] Hans Galen, cat. exp. Der Maler aus Münster zur Zeit des Westfählischen Friedens, Johann Bockhorst, Münster, 1998; Maria Galen, Johann Boeckhorst, Gemälde und Zeichnungen, Hamburg, 2012, pp. 464-9.

[8] Red and black chalk with white highlights, 30.1 x 21.0 cm, unsigned and undated, Stadelmuseum, Münster, inv. nr. ZE-0986-1

[9] Susan Barnes, Nora de Poorter, Oliver Millar, Horst Vey, Van Dyck. A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, Yale, 2004, p. 128, Portrait of a Man, I. 146.

[10] Jacques Foucart, Catalogue des peintures flamandes et hollandaises du musée du Louvre, Paris, 2009, p. 132.

[11] Barnes et al. p. 128

[12] Irene van Thiel-Stroman, ‘Pieter Claesz Soutman’, in Painting in Haarlem 1500-1850: The collection of the Frans Hals Museum, Neeltje Köhler (ed.), Ghent, 2006, pp. 305-11; Kerry Barrett, Pieter Soutman: Life and Oeuvre, Amsterdam, 2012.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ryszard Szmydki, ‘Czy holenderski portrecista Pieter Claez. Soutman (1580-1657) byl w Polsce?/Was the Dutch portrait painter Pieter Claez. Soutman (1580-1657) ever in Poland?’, Kronika zamkowa/The castle chronicle, 2003, p. 38. The portrait was destroyed in the Coudenberg Palace fire in 1731.

[15] J. Denucé, Na Peter Pauwel Rubens, Documenten uit den Kunsthandel te Antwerpen in de XVII eeuw van Matthijs Musson, Antwerp, 1949, pp. 27-28, translated by Michael Lomax:

Monsieur Musson,

…

Het konterfyt van Van Dyck na my, wort soo hooch gheestimeert, als imant ietz van Van Dyck, gesien heeft, t’welck oock wt myn handen niet sal gaen ofte moet 300.guld.gelden. Dit, beminde vrient, is tot soet verhael, ende per occasion door den brengher deses gheschiedt, syt minnelicke mitt Ul gansse familje gegroet ende Godt almachtich in gnade bevolen, van

Ul. dw.en veel toeghedane vrient

Petr Soutman

Pittore di Sua maesta de Polonia

8. february In Harlem

A° 1645

16] Antwerp, Stadsarchief/FelixArchief (FA), Insolvente Boedels, IB 304, letter discovered by Piet Bakker, Archival Research Fellow, Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project and translated by him and Joost Vander Auwera from the original.

Monsieur Musson,

Ul. 2: Briefen ontfangen, den Inhoud verstaan, Tis Immers Al verleeden 4: a 5: maanten, of meer, Ick wegens Cortosij Ul. hebbe geschreeffen, t’ sij Een huijs Burgundia offe iets diergelijcks, t’welck bij sigr Moermans, te vinden is, (Ul. geven soud) Tis seeker Een onnosele saack een 2: Jaar na sijn Gelt te wachtten, En dan noch &c, Doed daar in naart’ Jenijghe sood weesen moed, Ick waar Al bij Ul. geweest, dan mit het sterffen van mijn schoonvadr Ende het Bevallen op Paasdach mit mijn liefste Int kinder bed van Een Jongedochter, is sulcx beled dan verhoop in 2: a 3: weeken bij Ul. te sijn, Ul. het gelt ondertuschen ontfangen hebbende wilt dat tot mijn komst behouden, Ick sal Apparentelijk mit sijn Hoocheijt spreecken, want dat mijn konterfaijt daar is, heeft sijn Bedietsel, En soo die Betaling voor die tijt dan nogh niet er is, sal Ick sijn hoogheijt daar self van aanspreeken, dit Beminde vrient tot Ul. governe, Ende Blijve nederen gebiede moghe hr. monsieur Ul Dienaar

P[ieter] S[outman]

Aprilis, Haarlem 1651

[17] Smyzdki 2003, p. 37. They were all destroyed in the Coudenberg fire 1731.

[18] 1 guilder = 20 stuyvers.

[19] Erik Duverger, Nieuwe Gegevens Betreffende De Kunsthandel Van Matthijs Musson En Maria Fourmenois Te Antwerpen Tussen 1633 En 1681, Gent, 1969, p. 73, translated by Joost Vander Auwera:

f° 42v°

Betaelt aen Sieur Adriaasen den 4 febriwary 1651 in de Peter Potsstraet de

somme van Fl. 78-19

In promesie 3 stuyvers penninghe, voor rekening van Sieur Peeter Soutmans

tot Harlem ende ick moet van hem hebbe 9 printen en half tot 48 stuyvers

stuck Fl. 22-16

Afgetrocken in courant gelt macken seamen 101 guldens 15 stuyvers, dat ick

voor Sieur Peeters Soutmans ontfanghen hebbe van Menheer David Teniers tot Brussel

100 guldens promise 3 stuyvers penninghe

[20] Haarlem Archives, inv. no. NL-HlmNHA_53014144_1; published in Geschiedkundige Aanteekeningen over Haarlemsche Schilders en andere Beofenaren Van De Beeldende Kunsten, voorafgegan door kene Korte Geschiedenis van het Schilders-Of St. Lucas Gild Aldaar, A. van der Willigen, Haarlem, 1866, p. 190.

[21] Haarlem Archives, inv. no. NL-HlmNHA_53014144_M.

[22] Arnout Balis, ‘Rubens and His Studio: Defining the Problem’, in exh. cat. Rubens. A Genius at Work., Brussels, 2007, pp. 30-51; Arnout Balis, Rubens Hunting Scenes, Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, Vol. 18, no. 2, Oxford, 1986, pp. 38-41.

[23] Philip Rubens, Via Petri Pauli Rubenii, undated manuscript transcribed by the Baron De Reiffenberg, ’Nouvelles Recherches sur Pierre-Paul Rubens, contenant une vie inédite de ce grand peintre, par Philippe Rubens, son neveu, avec des notes et des éclaircissemens recuellis’, Nouveaux Mémoires de L’Acadèmie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Bruxelles, Volume 10, Brussels, 1837, pp. 10-11.

[24] Translation by Karin Zeleny, amending the English translation of L. R. Lind, ‘The Latin Life of Peter Paul Rubens by his Nephew Philip A Translation’, The Art Quarterly, Vol. IX, No. 1, 1946, p. 41.

[25] E. Duverger, “Soutman, Pieter Claesz”, in: Nationaal Biografisch Woordenboek (Koninklijke Academie van België), Brussels, 2002, Vol. XVIII, pp. 715-718.

[26] Wojciech Tygielski, exh. cat., De prinselijke pelgrimstocht. De “Grand Tour” van Prins Ladislas van Polen 1624-1625. Antwerp, 1997.

[27] Xavier F. Salomon, ’Van Dyck in Sicily’, in the exh. cat. Van Dyck In Sicily 1624-1625 Painting and the Plague, Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2012, pp. 15-51

[28] Ryszard Szmydki, ‘Czy holenderski portrecista Pieter Claez. Soutman (1580-1657) byl w Polsce?/Was the Dutch portrait painter Pieter Claez. Soutman (1580-1657) ever in Poland?’, Kronika zamkowa/The castle chronicle, 2003, p. 37. They were portraits of Sigismund, his second wife, Constance of Austria, Queen of Poland (1588-1631), and her nephew and step-son Prince Ladislaus.

[29] ibid p. 36, copied from Brussels, Archives générales du Royaume, Audience nr 1057 (Passeports pour marchandises 1627-1631), fol. 162. The duration of the pass was left blank:

Isabel etc,

A tous nos Commis, nous avons donné et donnons par ceste, congé et licence à Pierre Soutermans de se pouvoir transporter des Provinces d’Hollande en celles de pardeça, avec une casse de pointures venue de Pouloigne pour nous. Nous vous mandons et commandons au nom de la part de Sa Majesté de la laisser avec ladite casse par tout librement et franchement aller, passer et retourner, sans rien, à durer de présent passeport le temps et terme de…mois. Faict à Bruxelles, soubz notre nom et cachet secret, le vingtième de novembre, 1628

[30] This painting of 23 life size personages, his largest group portrait, was destroyed in the French bombardment of the Grand Place, Brussels in 1695. Barnes et al. 2004, p. 4 & p. 396.