14 March 2017

Panels, Palazzos and Discoveries in Italy

JVDPPP recently undertook a whistlestop tour of Genoa, Cremona and Vicenza. In Genoa, we followed in the footsteps of Van Dyck himself to the Palazzo Rozzo, where his magnificent portraits of the Brignole-Sale family painted in 1627 still hang. In 1739, it is recorded that Don Giovanni Francesco III Brignole-Sale, who was the Genoese Ambassador to the court of Louis XIV in France, owned a Christ and twelve Apostles by Van Dyck. The Christ remains in the Palazzo as it was given to the city of Genoa in 1874. The twelve apostles were sold in 1914 to the Munich based art dealer Julius Böhler. They are now spread around the world. JVDPPP is travelling to study them one by one – if anyone knows the whereabouts of Matthias, last seen at Christie’s in 1929 please let us know!

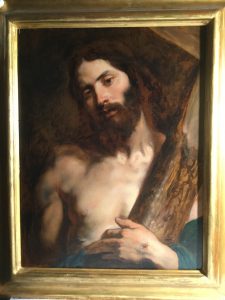

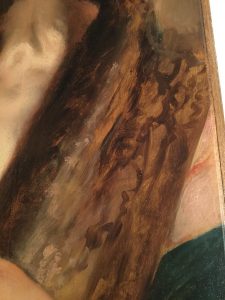

The Christ is beautifully painted by a young Van Dyck, still in his teens or very early twenties. A clear mark of his genius is the sheer economy of effort used to create the bark on Christ’s cross. It is achieved by a few swift strokes of paint on the brown under layer (imprimatura) of the panel.

We examined the painting and its oak panel in the atmospheric surroundings of the mezzanine level, the former winter quarters, of the Palazzo. There are plans to open it to the public in the future. Joost spotted that there is probably under drawing in black crayon on the edge of the muscle on Christ’s right arm. This is an interesting discovery. Given that Van Dyck copied the Christ from a painting by Rubens (now lost, the accompanying twelve Apostles are in the Prado, Madrid), did he do a full drawing in black crayon before painting? Rafaella and Elisa, the curators at the Palazzo Rosso have kindly agreed to infra-red the painting and share the results with us.

Johannes found the tree growth rings on the edge of the panel. The three planks of Christ come from three different Baltic oak trees. The possible horror of dendrochronology would be to discover that the oak trees, that started growing in the Middle Ages, might have been cut down after Van Dyck died in 1641. However, in the case of Christ Johannes has calculated a felling date between 1600 and 1620. More excitingly, and a unique feature of our project, is that Johannes can determine whether the planks on the Christ are from the same or neighbouring trees as other Van Dyck panel paintings we have examined across the world. Initial indications are that this is indeed the case. Watch this space…

From Genoa, we drove to Cremona and La Pinacoteca Ala Ponzone of the Museo Civico, housed in the 16th century Palazzo Affaitati. We went to see a copy on canvas of Van Dyck’s panel painting of The Crucifixion with Saint Francis, now in the Courtauld Institute Gallery, London (oil on panel, 50 x 36 cm, inv. no. 303). The tightness and exactness of the drawing reminded us of the style of an Antwerp based artist who knew Van Dyck and his paintings well, Abraham van Diepenbeeck (c. 1596 – 1675). This copy proves the contemporary popularity of Van Dyck’s compositions. Given that this Crucifixion only entered the museum’s collection in 1960, we will be looking for mentions of this copy in old inventories and sales catalogues.

After Anthony Van Dyck, ‘The Crucifixion with Saint Francis of Assisi’, oil on canvas, 59 x 44 cm, Museo Civico Cremona, inv. no. 794

From Cremona to the Musei Civici di Vicenza and the Palazzo Bianco. We were searching for a little-known panel in the museum storage – The Adoration of the Shepherds. It is described in the most recent museum catalogue (2009) as a copy after Jacques Jordaens. It had entered the museum’s collections in 1902 as being a painting in the style of Erasmus II Quellinus (1607 – 1678). We were eager to see it. The museum catalogue records that the art historian Michael Jaffé had been consulted by the museum in 1957 and declared the painting to be a copy after Jordaens. However, we had also discovered that another Jordaens scholar, Roger d’Hulst thought differently and considered that the Vicenza Adoration was an original by Jordaens. This opinion was buried as footnote 49 on p. 331 on the notes to Chapter III in his 1982 monograph on the artist.

Jacques Jordaens, ‘Adoration of the Shepherds/Adorazione dei Pastori’, oil on panel, 66 x 51 cm, Musei Civici di Vicenza, inv. no. A 291

The 20th Century backing panel was removed. The reverse of the original oak panel revealed both a panel maker’s mark and the Antwerp brand mark of the Guild of Saint Luke. The panel maker’s mark is that presently ascribed to Guilliam Aertsens, who was active as a panel maker from 1612 (when he became a Master in the Guild of St Luke) to 1626 and possibly beyond.

The panel maker’s mark, top left, with the Antwerp brand of the Guild of St Luke, the Castle, lower centre, and the hands, top right

Johannes has determined that the panel is made from Lithuanian oak trees that we have found before on our travels. The trees would likely have been felled after 1611 and probably between around 1615 to 1625.

The front of the painting was also revealing. The eagle-eyed Frances Hargreaves, an intern at the museum in Vicenza, was the first to spot a ghostly head of a woman on the right of the painting. When and why was this head overpainted? By Jordaens or someone else? We are looking forward to receiving x-rays and infrareds from Chiara.

As the visits continue, we are gathering more and more material for our research on Jordaens, Van Dyck and panel marks. We will soon combine these object orientated findings with new archival research in the Antwerp and other archives when our Archival Research Fellows are appointed.

Thank you to Raffaella in Genoa, Mario in Cremona and Chiara in Vicenza for their kind facilitation to the paintings in their collections and the stimulating discussions that followed.

How to cite: Davies, Justin. “Panels, Palazzos and Discoveries in Italy.” In Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project.

jordaensvandyck.org/palazzos-panels-and-discoveries-in-italy/ (accessed 3 March 2026)