F. Jos Van den Branden

Deputy-Archivist of the City of Antwerp

Drukkerij J.-E. Buschmann, Rijnpoortvest, Antwerp, 1883

Translated by Michael Lomax, 2018

© Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project.

JVDPPP Note: Van den Branden’s biographical notice on Van Dyck is often cited. It remains important owing to the extensive documentation he found in the Antwerp archives. Until now it has never been published in English, only Dutch, so has not received the wide audience it deserves. It should be noted that Van den Branden refers to Van Dyck as ‘Antoon’ throughout. This is a 19th century Dutch version of his name, Antonio, which he did not use nor was he called in the 17th century. It is recommended that readers also consult more recent literature where some amendments are made where necessary. On the whole, however, this comprehensive notice, though infused with a late 19th century art historical slant, has successfully stood the test of time.

Rubens was required to make small-scale drawings himself of all these creations but was permitted to “have them worked up full size and completed by Van Dyck, as well as certain other disciples of his, as the pieces and their placing demanded”. In addition, Rubens was to promise “on his honour and conscience” to complete in his own hand all the paintings in which there was any defect. For one of the four side altars, the Master would deliver a painting free of charge, failing which he would be required to relinquish the thirty-nine drawings of the ceiling pieces to the fathers (of the Jesuit church). All the works were to be delivered by the end of the year (1620), thus in under nine months, at which time Rubens would receive 7,000 guilders for them. The contract closed with the declaration that if a new painting were also needed for the high altar, no one else than Rubens would paint it. It was promised to Antoon van Dyck that he “in due time” would also similarly be able to produce a painting for one of the four side altars.

ANTOON VAN DYCK

Antoon van Dyck remained working with Rubens for only a short time. His was such an independent talent that we consider ourselves obliged to give him a place of honour. The grandfather of this world-famous painter, also named Antoon van Dyck, was likewise born in Antwerp in 1529. He was a “hawker, travelling around and feeding himself with silk and little penny-ware[1]“. On 4 September 1568, when living in the Maanstrate[2] in the little house named “den Hercules”, he petitioned our Magistraat (city government) to be released from the duty of lodging Alva’s rough soldiers, arguing that his dwelling was too small to set up a bed for them. The hawker Antoon van Dyck also opened a shop in this house in which he is mentioned. Later, on 30 December 1579 he purchased, as a merchant, premises of his own, “Den Berendans” on the Groote Markt, opposite the Hoogstraat, at what is now number 4. There, he significantly expanded his business. Unfortunately, the hard-working man died on 3 March 1580. His widow, Cornelia Pruystinck, was left with three children, Frans, Ferdinand and Catherina, with whom she continued her business.

Her elder son Frans concluded a marriage contract on 8 September 1587 with Maria Comperis, the daughter of Jan and Anna Viruli. The marriage ceremony took place on 4 October in our main church. Although the newlywed now had his own family, he continued to live in “Den Berendans” with his mother. On 27 January 1588, he concluded an agreement with her and with his brother-in-law Sebastiaan de Smit, to trade as partners in sagathy silk, baize, finished linen and woollen goods, double-thread canvas, braid, fringes, cords, aiguillettes, yarns and ribbons. His mother brought 6,000 guilders into the business and each of her two partners 4,800 guilders. Business was excellent. The business expanded further, not only at home, but also abroad. Goods were dispatched to Amsterdam, Paris, Cologne and London. However, the well-being of the partnership was suddenly cut short by the death of his mother, who departed to the next life on 10 December 1591, in her house, “Den Berendans”. Frans van Dyck also lost his wife on 28 July 1589 in giving birth to a son, who was buried along with his mother.

However, on 6 February 1590, our young widower remarried, in our main church, a new life companion, Maria Cupers[3], daughter of Dirk and Catharina Concincx. As this second spouse of Frans van Dyck was particularly fertile and brought a child into the world nearly every year, the happy father saw himself forced, with his family, to live in Den Berendans alone. He rented this house from his brother and brother-in-law on 8 January 1596, for four years, starting at Christmas 1595.

Before the lease had ended, Van Dyck’s young mother had given birth to her seventh child, Antoon, who would become our famous painter. She was very adept with a needle, and during her pregnancy designed and embroidered in coloured silk a beautiful chimney cover, presenting the Story of the Chaste Suzanna. Her expected child, her favourite, was born on 22 March 1599 and baptized the following day in the main church.

On 17 February 1599, our future painter’s parents had purchased a house named “Het Kasteel van Rijsel” at 42 Korte Nieuwstraat but moved in only on 25 December once it had been refurbished and the lease on “Den Berendans” had expired. Nor did they remain long in this new dwelling. On 3 March 1607, they purchased another four properties in the Korte Nieuwstraat, including the house “De Stad Gent” at number 46, with a coach gate, yard, stalls and storehouses; plus, a gallery, superb rooms with permanent paintings, a bathroom and a large office. After bringing her twelfth child into the world, Van Dyck’s mother lay exhausted on her deathbed in the new house “De Stad Gent”. With her husband she made a codicil to their will of 17 February 1595, bequeathing 900 guilders to each of her nine surviving children.

The next day, her weeping children saw their beloved mother close her eyes forever. For the eight-year-old Antoon it was a double loss to be deprived of his art-loving mother, from whom he had received his skills, at so early an age. But father van Dyck did not lose courage with the departure of the mother of his household. For the good of his nine minor children he did not enter into a third marriage. Fortune would have it that, despite the bad times, his business held up pretty well. This enabled him to live comfortably and provide an attentive upbringing for his children. He even had them take music lessons. In his gilded leather-lined room stood “a beautiful double harpsicord, made by Master Jan Ruckers”, on which the daughters and little sons accompanied one another, as they rejoiced their hearts with the excellent Flemish songs of their day.

But as, however, all happiness is short-lived, this domestic happiness was disturbed to such an extent that it became a matter for the city and even the courts. On 4 December 1610, a certain Jacomijne de Kueck, born at Hondschoten, was publicly punished and banished for life from Antwerp “for continuing to compose, sing and disseminate certain defamatory songs, insulting and denigrating Franchoys van Dyck, citizen and merchant of this city, together with his daughters and household; and for having, on several occasions, at ungodly hours, broken the windows of the same Franchoys van Dyck, having further, during her imprisonment, made various threats to murder him, Van Dyck.” Antoon van Dyck was then no more than a child; but his tender heart must have been deeply shocked by the public shame brought upon his family. Notwithstanding, the gifted young man’s powers of mind developed early. His artistic bent had already revealed itself appropriately.

Aged just eleven, he entered into the studio of Hendrik van Balen in 1610. Barely an adolescent, he was already a skilled painter. At the age of just fourteen he painted, with neat and true colours, the telling Portrait of an Old Man, signing the canvas; Anno 1613 A.V.D. F. AETA. SUAE 14.

This remarkable young man’s bosom friend and fellow painter was Jan Breughel II, who was just one year younger than our Antoon. Later, this Jan Breughel was to testify in front of a public notary that “he truly had, from his young years, a great knowledge of and familiarity with the very famous artist Van Dyck, now deceased, with whom, being of almost the same age, he was brought up, and that when they had reached an appropriate age, they were together in Italy, having and maintaining there the same familiarity and friendship, always communicating to each other the business and art of the one and the other. The deponent had the same communication and communion with the same Van Dyck when, returning from Italy, he resided in this city[4], always seeing and being present when the same Van Dyck was working on new pieces and special works.”

In giving this testimony, which Breughel stated that he was ready to confirm on oath, he declared that, in 1615, before Van Dyck travelled to Italy, he, Breughel had been daily in the house of his friend and art companion Antoon. The young Van Dyck, who considered himself to have fully learned his profession, had already left his master Van Balen and was working for his own account in the house “Den Dom van Keulen” in the Langer Minderbroedersstraat, today named the Mutsaertstraat.

One day of that year, Jan Breughel came into Antoon’s studio and saw his uncle there, the old engraver Pieter de Jode, sitting as a model for the youthful painter. Breughel was surprised and at once asked Van Dyck: “What are you doing there?” Antoon answered unabashed: “I’ll make an attractive apostle of him.” And indeed, the brilliant young man painted not one, but all twelve apostles, along with Christ, on thirteen separate panels. This major order had been placed by Willem Verhagen, dean of the Guild of the Young Longbowmen, who was also an art dealer. This Verhagen also declared in an official deposition, that when he had exhibited the Twelve Apostles with the Saviour in his house, “the very famous artists Rubens, Zegers, Rijckaert, the art dealer Moermans and many others had visited him, for the sole purpose of seeing and visiting the aforesaid paintings, the which were amazed at the art of the same, which they always praised and acclaimed, as being made and completed by said artist Van Dyck in his own hand”.

Thus, at the age of sixteen, Antoon van Dyck was delivering works that were visited and admired by our most renowned painters. The fact that the great Rubens went to visit Van Dyck’s Christ and the Apostles at the buyer’s house and praised them proves that Van Dyck, who was already gaining a name, was at the time not yet the apprentice of the great master of our school of painting. Had the excellent young man already been under Rubens’ direction, then the latter would definitely not have needed to view the Apostles elsewhere than in his own “painting house”.

The fact that this young artist was working separately also bears witness to his early striving for independence. It tells us clearly that, in his view, he needed no other lessons after those of his Master, van Balen. Antoon then already had apprentices, including Herman Servaes who, according to his own testimony, was to copy one of the above-mentioned Apostles, after which Van Dyck retouched and completed it, like the great masters did when overloaded with commissions. The same apprentice testified also “that he, in the twelve-year truce between his Royal Majesty of Spain and the States of Holland”, thus between 1609 and 1621, saw his master, Antoon van Dyck, paint a Drunken Silenus, which is still exhibited in the Brussels museum. This is again proof that our Antoon had still not placed himself under the direction of the celebrated head of the Antwerp painters. It was as if Van Dyck was fully conscious of his own inborn talent and therefore avoided the direct influence that the all-dominant Rubens would exercise on him. It was also in the young man’s nature to strive for freedom and to provide, at an early age, for his independent existence.

On 3 December 1616, not yet eighteen, he sent already, in his own name, a petition to the magistrates of his city, complaining bitterly about his guardian brothers-in-law, who were refusing to pay out to him his inheritance from his grandmother. Despite his being a minor, Antwerp’s Magistraat gave him leave to force his guardians to give account in front of the city commissioners. Not yet satisfied with the same, he also presented himself on 13 September 1617 as the protector and defender of his “brothers and sisters, being also minors and very young”. Armed with the written power of attorney of his father, who entrusted to him the settlement of the family matters, he requested this time to be allowed to force the guardians to settle with his brothers and sisters, and this was granted to him.

On 15 February (1618), his father Frans van Dyck gave power of attorney to public prosecutor Cornelis de Brouwer “to appear in the Higher Court of our Gracious Lord the Duke of Brabant, and there, with all solemnity, and according to the law of the same Higher Court, to emancipate and remove him from his duty and bread; thus he emancipates and removes from his duty and bread, herewith, Antonis van Dyck, his son, painter, in his nineteenth year, proving and assigning herewith, two old large or Brabant stuivers at his house called De Stadt van Gendt, in the Corte Nieuwstraat of this city.” The day thereafter we see Antoon van Dijck declared independent in our court, and from now on he appeared as a freeman in Antwerp.

At this point he painted his own portrait, writing at the back on the panel his name with the declaration that he had depicted himself in 1618 at the age of nineteen. He presents himself extremely simply, as a beardless young man, with friendly eyes, finely-cut and regularly shaped face, his already broad forehead still partly hidden under masses of slightly curling hair, falling down in waves onto his neck.[5]

Van Dyck who, also still so young, had already become famous, could not continue to paint longer without purchasing his free mastership from our St Luke’s Guild. On 11 February 1618, he paid there 23 guilders and 4 stuivers for this. His acceptance as a member of the Painters’ Chamber must have been festive, with the imbibing of large quantities of drink, as on 17 July he paid a further 15 guilders wine money. This purchasing of his free mastership is again proof that Van Dyck had not yet any intention to follow so many other talents and enter into Rubens’ service.

The first definite written evidence of Antoon’s entering into Rubens’ orbit is the contract signed by the great master with Jesuits, wherein on 29 March 1620 the latter commissioned, for their new church, thirty-nine paintings, to be completed within nine months. As mentioned above, Rubens was required to produce himself the small-scale drawings of the works, but was permitted to “have them worked up full size and completed by Van Dyck, as well as certain other disciples of his, as the pieces and their placing demanded”. Van Dyck is the only one of Rubens’ co-workers to be mentioned by name. This means that from the start he must have been viewed as the most noteworthy and his services particularly valued. A fact that confirms even more our Antoon’s fame is the fact that, in the same agreement, the praepositus of the Jesuits undertakes to allow him, Van Dyck, “in due time” to design and execute a painting for one of the side altars of the church. Van Dyck does not appear, however, to have availed of this particular favour. On the contrary, he painted for the church of our Dominicans a Christ Bearing his Cross, which is still exhibited there.

At the same time, he painted six superb pictures based on the tapestry cartoons for Rubens’ History of the Death of Decius Mus.[6] While our young painter was producing these works and was helping complete the paintings for the Antwerp Jesuits, he had also taken up residence in Rubens’ palace, as appears in a letter from 17 June 1620 to the English Earl of Arundel. This letter, in Italian, and sent from Antwerp to London, contains these sentences: “Van Dyck lives permanently at Mr Rubens’ house and his works begin to be esteemed almost as highly as those of this master. He is a young man of twenty-one, of a very rich father and mother of this city. This will make it difficult to get him to move from here, the more so as he sees the fortune that Rubens is making here.”

This tells us that the high and mighty Earl of Arundel, whom Rubens called the evangelist of the art world, was already making attempts to lure our famous painter Van Dyck to London. Even before the ceiling paintings for the Jesuit church were completed, he apparently succeeded. On 25 November of the same year, another Englishman, Toby Matthew, wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton, ‘Your Lordship will no doubt have learned that Van Dyck, Rubens’ famous allievo, has moved to England, and that the King has granted him a pension of 100 pounds sterling a year.’ Our twenty-one-year-old must have given a superb account of his talent at the English court, being permitted to depict the image of the reigning monarch James I, life size and after nature, on canvas.

On 16 February 1621, the King had 100 pounds sterling paid to him for a special service done for His Majesty. On the 28th of the same month, Antoon van Dyck is referred to as the King’s servant; yet already he receives a letter of safe conduct to travel for eight months. This travel was something of a farewell to the English Court, to which Van Dyck would not return for ten years. In which regions Antoon spent his time after leaving London is not known with certainty.

While still absent from Antwerp, he received the sad tidings that his father was mortally sick in bed. Like the loving son that he was, he hurried to the parental home to offer the sick man comfort and support. The sufferer was extremely well looked after by the Dominicans, and Antoon’s childlike love could not prevail against unrelenting death, which came and took the beloved father. When Van Dyck the elder died on 1 December 1622, Antoon was at his deathbed. In this heart-rending moment, the dying man had his son promise to paint a painting for the Dominicans, who had shown him “certain friendship and loyalty” during his sickness. The loss of his father affected the sensitive young man so deeply that he had neither the courage nor the strength to fulfil his promise to the dying man at that time.

No doubt the afflicted young man went to seek comfort from the open-hearted and noble Rubens; because it is said that the great master advised Van Dyck at this time to make an art journey. Our young painter was at that time still a welcome guest in the Rubens palace, even being allowed to set up his easel there. Alexander Voet, the seventeenth century Antwerp engraver, owned a valuable painting “The Portal at the Place of Rubens’ House”, painted by Van Dyck. Before setting out on his journey, Antoon also painted Rubens’ portrait, and that of his worthy wife, which excellent works he gifted to the Lord and Master in memory of himself, with another of his paintings, the Seizure of Christ in the Garden of Olives. In exchange for these gifts the prince of painters offered his young art friend the best horse in his stable to bear him to Italy.

Although young in years, Antoon was now a robustly grown and attractive man. His self-portrait, now exhibited in Florence, shows us him, at about this time, with large amounts of blond, half curled hair, his small mouth decorated with a light moustache and a little beard on his underlip. His face is dignified, with an almost maiden-like finesse. He has a high, flat forehead, an attractive, strongly-cut nose and a short, round chin. A soft bloom gives a pinkish hue to his jaws, and his lively brown eyes radiate joie de vie, friendship and affection. It was Van Dyck’s custom to express people’s graciousness and good standing by means of rich and tasteful adornment. Here he wears a proud feathered hat, a wide turned-down lace collar, a doublet and breeches of coloured slashed velvet and satin, while his silk hose is half hidden in his fine leather boots, with gleaming spurs at their high heels. When now, seated on Rubens’ superb steed, he rode with proud step out of Antwerp’s gate, many a pretty maid must have regretted that such a pretty Signor had escaped her.

One of these pretty women must have watched him depart with a broken heart and reproachful eyes. On her mother’s breast lay the poor bastard child, Maria Theresia, whose father he was[7]. The disloyal lover appears to have been little disturbed by his youthful faux pas, as he was not in a hurry to reach the other side of the Alps. Instead of taking the shortest route and remaining on a straight road, he turned aside to the very picturesque Brabant village of Zaventem, where he met a highly appealing maiden. However, as the story goes, this was no simple and gentle farmer’s daughter, but rather a slim, richly adorned and high-born maid. As the spry wooer was not at his first affair, nor was it his manner ever to dampen the glow of his easily inflamed love, he betook himself without hesitation to the house of the beautiful maiden, introducing himself as a painter.

The father of his lady love, Marten van Ophem, bailiff of the Zaventem Baanderij, was a noble art lover, and the elegant painter was very welcome in his house. He immediately proposed to him to paint an altarpiece for Zaventem church. As the love-struck Antoon was permitted to design and complete this work of art in the very house of the angel of his dreams, it is easy to imagine how eagerly he accepted the proposal. The panel was to portray Saint Martin sharing his cloak with the beggar, the saint being the patron of both the commissioner and of Zaventem church. [8] As long as Van Dyck was working on the painting, he enjoyed board and lodging in the house of his beloved, but as the painted neared completion, he could not bring himself to deliver it and take his leave. Then, in order to lengthen his stay and to attain his final goal, the enamoured artist declared himself ready to donate a painting from his own hand to Zaventem church. This second altarpiece that he painted there was a Holy Family[9], with the woman he venerated, the graceful lady Isabella van Ophem, depicted in it as the Holy Maid.

With the second masterpiece now exhibited in the village church, Van Dyck judged that the favourable moment had come to ask for the hand of the lovely high-born lady van Ophem in marriage. Unfortunately, her proud family found this request unacceptable. Under the pretext that the noble Isabella was still too young to enter into marriage, our tender-hearted painter was ungracefully put out of the house. The noble-minded Rubens makes an appearance again in this prickly moment as the saviour and comforter of his young artist companion. Popular narration has it that the great master went and found the distraught lover and encouraged him a second time to undertake the art journey that would heal his wounded heart. A sound talking-to was sufficient to get him to understand his real condition, suppress the sickly pains of his heart and raise his pretty and gifted head. With a thankful handshake he took leave of the wise counsellor, and immediately sprang into the saddle. He spurred the proud stallion and this time trotted directly in the direction of Italy.

The first place where our traveller settled was the rich trading city of Venice, where so many a famous painter had left his masterpieces. Here, Van Dyck studied Paolo Veronese and Tiziano Vecellio in particular, of the latter of whom he copied various natural and richly-coloured portraits to take back with him to his fatherland. Once our painter had admired the series of excellent works in this city, he moved to the no less proud Genoa. There he received an excellent welcome and was permitted to paint several of the foremost persons from life. In a masterly manner he painted portraits of Giovanni Paolo Balbi, Guilio Brignole and the Marquis of Spinola, all on horseback with shining steel harnesses, as well as the Doge Pallavicino in the dress of ambassador to the Holy See.

At the same time, our young master painted an Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi and the Resurrection of Christ. In the eternal city, Van Dyck also painted the portrait of Sir Robert Shirley, in eastern attire, as the ambassador of the Kingdom of Persia in Rome, along with this statesman’s wife, the famous Brussels sculptor Frans Duquesnoy and many of the highest nobility, with whom our painter was in daily contact. The fact that Van Dyck spent his time in Rome in the highest circles of society ignited the jealousy of his fellow-countrymen and artists. The Netherlandish painters visiting Rome had founded there an association, the kunstenaarsbent. All fellow-countrymen arriving in the Eternal City were required to register in this association, after which they received a special nickname, making reference to their particular artistic direction, their descent, their relations or their defects. Newcomers were expected to stand their colleagues a feast, and on these and other occasions they generally ate and drank so immoderately that the association’s members forfeited either their fortune or their health. Our Antoon, who behaved in Italy in so distinguished a manner and dressed so distinctively that he was named il pittore cavalleresco (the knight-painter), considered it beneath his dignity to be accepted into the dissipated kunstenaarsbent. The members of the despised association took this badly, calling their exceptional fellow-countryman a proud-neck; they bad mouthed him and persecuted their brother artist so much that, in 1624, with regret, he left Rome and returned to Genoa.

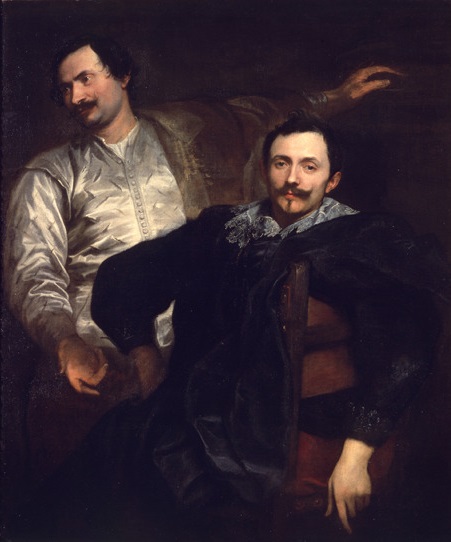

A certain number of church paintings were also ordered from him in Genoa, including a Pietà and an Ecce Homo. In the same city, Antoon visited his city and art comrades, the brothers Cornelis and Lucas de Wael, whom he depicted so masterfully on a single canvas.

At the De Wael brothers’ house, Van Dyck also met their cousin Jan Breughel II, who must have received his bosom friend Antoon with no little joy. With this latter Antwerp artist Van Dyck travelled on in summer 1623 to Rome, where they remained on the most intimate terms. Our famous portrait painter was lodged in the papal city in the palace of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio, former Nuncio at the court of Brussels. This lord of the church, praised by Cornelis Hooft as the most excellent non-native writer on the history of the Low Countries, held Van Dyck in high esteem. He had him paint his portrait sitting and also commissioned from him a scene from the Sufferings of Christ.

At the same time, our young master painted an Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi and the Resurrection of Christ. In the eternal city, Van Dyck also painted the portrait of Sir Robert Shirley, in eastern attire, as the ambassador of the Kingdom of Persia in Rome, along with this statesman’s wife, the famous Brussels sculptor Frans Duquesnoy and many of the highest nobility, with whom our painter was in daily contact. The fact that Van Dyck spent his time in Rome in the highest circles of society ignited the jealousy of his fellow-countrymen and artists. The Netherlandish painters visiting Rome had founded there an association, the kunstenaarsbent. All fellow-countrymen arriving in the Eternal City were required to register in this association, after which they received a special nickname, making reference to their particular artistic direction, their descent, their relations or their defects. Newcomers were expected to stand their colleagues a feast, and on these and other occasions they generally ate and drank so immoderately that the association’s members forfeited either their fortune or their health. Our Antoon, who behaved in Italy in so distinguished a manner and dressed so distinctively that he was named il pittore cavalleresco (the knight-painter), considered it beneath his dignity to be accepted into the dissipated kunstenaarsbent. The members of the despised association took this badly, calling their exceptional fellow-countryman a proud-neck; they bad mouthed him and persecuted their brother artist so much that, in 1624, with regret, he left Rome and returned to Genoa.

Meanwhile, Antoon’s family were hoping for his return, his departure from the fatherland having appeared over hasty. His brother-in-law, Antwerp notary Adriaan Diericx, wrote on 27 September 1624 to the city’s Magistracy that “Antoni van Dyck, having now reached his majority, has removed himself abroad without leaving anyone to look after his affairs”. The famous painter concerned himself little at the time with the management of his money and his family matters. Whilst he was being sought for this reason, he travelled to Sicily. There he received the distinction of being allowed to paint the portrait of the Viceroy Philibert Emmanuel of Savoy. The Brotherhood of the Holy Rosary also commissioned an altarpiece from him, but together with this already-commenced work Van Dyck had to flee from the plague, which burst out in a terrible manner, taking the Viceroy to the grave. The Antwerp artist’s place of flight was once again Genoa, where he completed the painting he had started and from where he sent it to its intended location. On a visit to Milan, Van Dyck copied the famous Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci.[10]

On his return journey via Turin, our painter came into the company of the wife of his former protector, the Earl of Arundel, who was on an art tour with her two sons. This meeting was a source of mutual pleasure. The illustrious English noblewoman pressed strongly to have the pleasant and talented painter decide to travel with her to London. Van Dyck thanked her politely for the distinction and returned to Genoa, where he was the house guest of his beloved friend Cornelis de Wael. On a new art tour in Florence, Van Dyck painted the portrait of his famous fellow-citizen Joost Sustermans, court painter to the Duke of Tuscany.

After visiting various other art cities, he turned his steps to his fatherland. On 12 December 1625, his brothers and sisters declared in front of the Antwerp Aldermen that Antoon was still outside the country. Older writers have it that he returned to his birthplace in 1626, but of this we find not the slightest trace. Before returning the Antwerp, he may well have visited Holland, because resplendent in the museum of The Hague is the Portrait of Sir Sheffield, governor of Briel, signed as follows: aet.svæs: 37. 1627. Ant.° van Dijck fecit.

The first certain proof of Antoon’s return to Antwerp is dated 6 March 1628. On this day, Antoon van Dyck made his last will and testament in our city. The notary confirmed that the painter was unmarried and in good health. The twenty-nine year old master commended his immortal soul to his creator, ordered that his mortal body be placed in consecrated earth, and chose his place of burial in the choir of the church of the Antwerp beguinage, where his sister Cornelia had been laid to rest on 18 September of the previous year. He appointed his other sister-beguines, Suzanna and Isabella, as his general testators, on condition nonetheless that, after his death, they take “Tanneken van Nijen, the old serving maid of himself and his late father”, and feed and clothe her for her remaining life. Should this be too difficult for them, they could pay Tanneken 100 guilders a year. The legacies which they were required to pay also after his death were 6 guilders to the Sint Jakobskerk and 24 guilders to the poor of our city. Following his sisters’ death, his entire fortune was to pass three-quarters to Antwerp’s “home poor”[11] and the remainder to St Michael’s monastery.[12] Nine days later, the Van Dyck beguines similarly enacted a mutual will which determined that, after the death of both of them, their property would pass to their brother Antoon or his legal successors. We take this as evidence that it was only at the start of 1628 that Van Dyck clearly took up residence in Antwerp. From that year also dates his registration with the fraternity of the Bachelors.

In that year too, he painted for the left side altar of our Augustijnenkerk the superb scene: Saint Augustine in ecstasy before the Holy Trinity, considered to be his first church work following his return from the south. He was paid 600 guilders for the masterpiece, still resplendent today in its initial location. The fame Van Dyck had now acquired led to his being invited to the Northern Netherlands. There, he painted the portraits of Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange, and his wife, Amalia van Solms and of their children and of various statesmen and artists. The following year, our celebrated portrait painter was back in his home city. Then he remembered the promise he had made to his dying father, and painted for the Predikheerinnenkerk (church of the Dominican sisters) the impressive painting: Christ on the Cross. At the same time, he painted for his above-mentioned fraternity, for 300 guilders: Saint Rosalia kneeling before the Infant Jesus and Mary, accompanied by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, together with another masterpiece, The Mystical Marriage of blessed Hermanus Josephus, for which he was paid a mere 150 guilders.

After that, our fertile painter painted for the Antwerp Minderbroederskerk (Franciscan church) the poetic small Pietà[13], and for our beguinage church the large Pietà[14], both of which are today in the Antwerp museum (Nos. 404 and 403), along with the little panel Christ on the Cross[15], also in the same collection (No. 406), and which comes from the Antwerp Augustinians. To the Kapucienenkerk (Capuchin church) in Dendermonde, Van Dyck delivered a superb Calvary, which is today admired in the main church of the same city. He also painted other beautiful and touching Calvaries, for the Minderbroederskerk (Franciscan church) in Mechelen[16], for the Sint Michielskerk (St. Michael’s church) in Ghent, and for the Minderbroederskerk (Franciscan church) in Lille, the which latter painting is now in that city’s museum. At the same time, he produced for the Kapucienenkerk (Capuchin church) in Brussels a Saint Antony with the Infant Jesus and a Saint Francis in ecstasy before the Crucifix, both of which works are now conserved in the Brussels museum.

The industrious artist must have illuminated other of our temples with his superb altarpieces. Today there still exist, from his hand, in the Brussels museum, a Martyrdom of Saint Peter; in the Louvre Our Lady with the Christ Child, between a kneeling Man and Woman, Saint Sebastian assisted by Angels and the Holy Maid with the Infant; in Valenciennes the Martyrdom of Saint James; in Lille the Miracle of Saint Antony of Toulouse; in Munich the Burial of Christ, the Holy Family, the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, Christ on the Cross and a Pietà; at Dresden Saint Jerome, Mary with the Christ Child and Jesus on the Globe; in Braunschweig Mary with her Divine Child; in Vienna, in the Lichtenstein gallery, The Burial of Christ; and in the Belvedere, Christ on the Cross, the Holy Family, and Saint Francis in ecstasy; in Berlin the Crowning with Thorns, the Flagellation of Christ, a Pietà and Our Lady with Jesus in her Lap; in Saint Petersburg the Holy Family, the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, the Flight into Egypt and Saint Thomas; in Florence Christ being mocked by the Soldiers and Christ on his Mother’s lap; in Madrid the Crowning with Thorns, a Pietà and Saint Francis of Assisi in ecstasy.

For the Antwerp kunstkamers (private art collections), Van Dyck also painted a number of superb works. Apart from the already mentioned Seizure of Christ, Rubens owned his: Antiope and Jupiter transformed into a Satyr, three Saint Jeromes[17], Saint Ambrose, Saint Martin, the Crowning with Thorns[18], the Head of Saint George, and The Head of an Armed Man. Other 17th Century Antwerp art lovers collected more than one hundred paintings by Antoon Van Dyck. To list all these works would demand too much space. However, we will list the Van Dycks from one kunstkamer, together with the prices at which the painters-art valuers Jan Erasmus Quellinus and Peter van de Willighen valued them:[19]

Two Angels, on panel Fl. 400

A Face with naked shoulders, on panel 60

St Francis at our Lord’s feet 350

A head of Christ 72

A sketch of the Magdalene’s Face, pasted onto panel 60

The portrait of Brussels City Pensioner Karel Schotte, on canvas 125

A sketched Face, on panel 50

A sketched Old Man’s Face, with green dress 50

A Portrait of a Man, with lace-cuffed hand on his breast 200

Woman’s Face, with hanging hair, paper pasted onto panel 80

Portrait of a Man with a white beard 60

A sketch of Hermida and Renaldo 300

A sketched Nativity 72

A Portrait with coat and hand 200

A Woman’s Face with white and black ‘coove’ 100

Two portraits of Cornelis and Lucas de Wael, on a single canvas 600

Two portraits of Jode Father and Son, on a single canvas 700

A Portrait with two hands with hanging lace cuffs, on panel 100

Our Lady at the Crib with the Ass 250

Two knee-length portraits “Rabat with his Wife” 300

Saint Peter and Saint Paul, canvas pasted onto panel 400

Saint Jerome, on panel 350

A Woman in an armchair 450

A Man in a wooden chair 72

The Sick Man taking up his bed 800

Saint Jerome, in a landscape, on canvas 250

“Charles Stuart, King of England, and the Queen” – two items 1,200

Saint Xavier with Our Lady, canvas on panel 800

Christ on the Cross, on canvas 800

Saint Jerome, on canvas 1,000

Saint Sebastian, large canvas painting 1,000

A Woman with Infant “presenting a pair of gloves”, on canvas 800

Van Dyck also painted a number of superb works taken from fables and bible stories. Those still preserved today are, at the Belvedere in Vienna, Venus at Vulcan’s forge seeking weapons for Aeneas, and Samson and Delilah; in the Dresden Museum, Jupiter casting himself as golden rain on Danae; at Hampton Court outside London, Cupid slumbering with the nymph, and in the royal country residence of Het Loo, Prince Willem III once owned theses sumptuous paintings by the master Van Dyck: Time Clipping Love’s Wings, Achilles among the Maidens, The Four Images of Love , and the School of Love, which were sold together for 12,825 guilders.

By delivering so many expensive paintings, Antoon van Dyck rapidly became one of our wealthiest citizens. When the city of Antwerp issued a loan of 100,000 guilders by royal grant of 20 March of 1630, the artist Antoon van Dyck subscribed 4,800 guilders, earning him 300 guilders in interest.

The young furore-making master was then summoned to court, where he painted the portrait of Archduchess Isabella, while also depicting on canvas her counsellor, the Marquis of Aytona, commander-in-chief of the Spanish armies in the Low Countries, bare-headed, in armour and with his staff in his hand, sitting on his magnificent white horse, life-size and majestic. Our art-loving ruler valued Van Dyck’s talent so highly that she appointed him her court painter, with an annual salary of 250 guilders. When, on 27 May 1630, our painter lent power of attorney in Antwerp to his fellow artist Peter Snayers, resident in Brussels, he fashioned himself “Antonio van Dyck, painter to Her Majesty”, an honorary title that was lost to later generations. This power of attorney served to demand payment for art work from “various persons” in Antoon’s name, “and specially to collect and receive in his name the annual pension of 250 guilders a year, which Her Majesty had granted to him, Antony van Dyck”.

Although Van Dyck was the court painter, he continued to reside in his city of birth, where in June 1630 he instigated court proceedings for the non-payment of his paintings. At the end of this same year the famous Erection of the Cross of the Saint-Martenskerk in Kortrijk was also commissioned from him. For this creation our master made a preliminary sketch. As this pleased the sponsors, he wrote on 8 November 1630 to the Kortrijk canon Rogier Braye, asking 800 guilders for the execution of the altarpiece which he had designed. The canon found this sum excessive, and the following day sent the following reply in verse:

“I wish to write and scrape no more;

Thus this is the final resolution of the matter:

One hundred pounds and no more will I give Signor Antonio,

So that his fame may live in Kortrijk and his art in our church.

And if he is not ready to accept and rejects the offer

He will be very unwise and badly advised,

And will lose much profit from others.”

Van Dyck accepted these poetic terms. He set to work, and along other works, the altar painting was ready in five months. On 8 May 1631 it was rolled up and sent by freight cart to Kortrijk. With the altarpiece resplendent on the altar, they also asked for the sketch; but in Van Dyck’s absence his servant said “this was no way of doing things”. Master Antoon himself was not so fussy. On receiving the specified payment for this work, plus, by way of satisfaction, twelve of Kortrijk’s famous sugar waffles, he wrote:

“Mr Braye,

Your pleasant missive of 13 of this month has been handed to me, together with a box of waffles, and I have also received, via Mr Marcus van Woonsel, the sum of one hundred Flemish pounds as payment for the painting commissioned by yourself, for which I have given the appropriate receipt to the said gentleman, thanking you for both the payment and the waffles. I had tried hard, in this work, to give you satisfaction, which (as pleases me) you have you fully had, as have the Reverend Deacon and the other Canons. The request to receive, pro memoriam, the sketch of the above item, I will not refuse, although I allow this to no others. To this end I have sent the same to Monsieur van Woomsel, to send to you. With which, offering to serve you where possible, I send you my best wishes and wish you a long and happy life.

Sir,

Your humble servant

ANT.° VAN DYCK

Antwerp, 20 May 1631”

In the meantime, our master had also been busy in the Northern Netherlands. On 12 February 1631 he sent from Antwerp a power of attorney for painter Lenaard van Winde in The Hague, to demand payment there from Adriaan Rottemont for paintings delivered. On 10 May following, Van Dyck, as godfather, held a daughter of the famous engraver Lucas Emilius Vosterman over the baptism font, with this little girl receiving the name Antonia. Later that year our master had to appear several times in front of the court of Antwerp, in order to demand payment for a painting that Boudewijn van Eck had commissioned from him.

After the French Queen Mother, Marie de Medicis, had been led into Antwerp by our governess Isabella, she visited not only Rubens’ palace, but also the residence of Van Dyck where, among other things, she admired a room of top quality paintings. The Queen Mother’s learned secretary, Pierre de la Serre, called the works the artistic jewels of Titian, taking the copies by Antoon van Dyck to be original paintings by the Venetian master. On the occasion of this honour-bestowing visit, our painter painted her Majesty’s portrait. De la Serre found this work more magnificent and complete than the best portraits by the greatest masters of the Queen Mother. He himself found it so surprisingly beautiful, that he could not help comparing the image of his mistress with Apelles’ painting of Helen. At the same time he permitted himself a very flattering comparison between the great Venetian master and our portrait painter. He said “Without flattery I can assert that Mr Van Dyck will shortly share the glory of fame with Titian. Because, just as that excellent painter was the jewel of his century, so this one will be the wonder of his.” This free-flowing praise, which this French historian waved in Van Dyck’s direction, witnesses the heights to which our artist’s glory had risen here.

His fame had also sounded again overseas. The Earl of Arundel, now Minister of England, renewed his attempts to get our master to London. For the account of an English nobleman, Endymion Porter, via a certain Mr Perry, a painting had been ordered from Antoon as a present for King Charles I. The fine work was speedily completed and paid for with 72 pounds sterling. Accompanied with a Spanish letter, Van Dyck had sent it to London on 5 December 1629. Thus, while Rubens was still at the English court, the King received Van Dyck’s painting, presenting the love affair of Armida and Renaldo. After this, his Majesty was shown the Portrait of Nicolaas Lanier, master of the Court chapel, and this other work made the British king an admirer of Van Dyck’s talent. Balthazar Gerbier, England’s ambassador to the Court of Brussels, also purchased a painting by Antoon van Dyck, the Holy Virgin with Saint Catherine, which he also sent in early 1632 to his Majesty. However, our painter hastened to inform his artist-colleague, Joris Geldorp, in London, that this work was not original. Gerbier was very angry at this news, which was so embarrassing for him, and which he called false. The sly diplomat assured everyone, high and low, that he had had no intention of cheating his King, maintaining that Van Dyck had wanted, preferably, to bring the portraits of Isabella and Marie de Medicis to London as proofs of his talent, but that he was unable to gain permission for this. Gerbier also brought in a painting retoucher as a witness to support the genuine nature of the suspect painting, maintaining it to be finer than the peer work that the Antwerp master had produced for the Northern Netherlands. He even asserted that Rubens had challenged Van Dyck to produce a more magnificent painting than the one that he refused to recognize as his own. According to Gerbier, Van Dyck was taking his revenge because he had not succeeded in having him invited speedily enough to the Court of London, and he was now disavowing his own work, as he was no longer minded to come to England. Our painter decided, nevertheless, from that moment, to undertake the overseas journey. He informed Gerbier of this, forcing him to write on 13 March 1632 from Brussels to his King: “Van Dyck is here, with the information that he has decided to go to England. He maintains that he is very badly disposed towards me, as the babbler Geldorp appears to have written that I had orders to speak to Van Dyck in your Majesty’s name and had kept this secret. Whereupon your Majesty imposed on me that I had no account to give to anyone, which I also maintain.”

To take his ship, Antoon travelled to the Northern Netherlands. According to verbal tradition, and also the writing of Dutch painter Arnold Houbraken, who lived from 1660 to 1719, Van Dyck had decided to visit his artist colleague and fellow-countryman Frans Hals on this journey, whom he had heard widely praised as the most competent of portrait painters. He boarded the tow barge and travelled to Haarlem. As the two famous portrait-painters had never seen each other, either in image or live, they did not recognize each other on their first meeting. When the loose and carefree Hals saw this pretty nobleman with feathered hat, velvet mantle, lace collar and cuffs turned back onto his satin doublet, his hands proudly gloved and his silk hose in wide-necked spurred boots enter his humble studio, he was totally confounded. Cap in hand, he asked to what he owed the honour of such a distinguished visit. Van Dyck, without revealing his identity, asked whether he was the Hals who could paint a portrait both excellently and quickly. The Haarlem painter bowed, and Antoon ordered him to make his portrait, quickly and well, as he needed to travel instantly. Without tarrying, Hals placed himself in front of an easel. He sketched and brushed, tested and tempered, and within half an hour requested the nobleman to stand and see whether the portrait pleased him. Surprised by such dexterity, Antoon approached and was amazed at this image, conjured onto the panel with such a masterly hand and so quickly. Recovering from his amazement, he declared informally; “But if it’s that simple, I’ll attempt to paint your portrait.” He picked up a canvas, placed it on the easel, and bade Hals sit for him. The latter smiled compassionately but set himself down happily as a model in the heavy Spanish leather armchair. However, on seeing the young lord remove his gloves from his fine hands and pick up palette and brush, Hals quickly realized that these fingers were not handling artists’ tools for the first time. The initially so off-hand nobleman was now staring at him with an inspired gaze. He watched him mix the colours unhesitatingly and, as it were, brandish his brushes like rapiers. He was even more surprised when all of a sudden it was announced “It’s ready”. Hals jumped out of the chair to the easel. On seeing his excellent portrait, the words escaped him “You are Van Dyck, because no one else can paint like that!”, and the two greatest portrait painters fell into each other’s arms.

Our Antwerp master’s stay in Holland was short. Still within a month of leaving his fatherland, he was already in London, since, from 1 April 1632, Edward Norgate, the Earl of Arundel’s art collector, received 15 shillings a day from the King for feeding Signor Antonio van Dyck and his servants. Charles I was, however, concerned to provide our painter with better accommodation. In his diary he wrote: “To speak with Inigo Jones about a house for Van Dyck.” The above-mentioned person was the King’s architect, and his Majesty quickly had the pleasure of offering his new painter two dwellings: a winter dwelling in Blackfriars, and a country residence in Eltham, in the county of Kent. England’s king found much pleasure in his energetic, well-mannered and talented painter. He had him paint his portrait repeatedly, and the queen and her children also often had their portraits painted. Many times, the King would leave his palace in Whitehall, and travel along the Thames on his barge to visit Van Dyck. He would then spend hours in the artist’s house, watching him conjure with his paintbrushes, or listening to his wise advice on art matters. The King granted Van Dyck the title of “special painter in ordinary to his Majesty”, with an annual wage of 200 pounds sterling, while everything that he painted for the Court was paid separately. Our Antwerp master had been hardly three months in London and Charles I already wanted to knight him. This took place on 5 July 1632 in St James’ Palace, where the Court was gathered. After the King had knighted his leading painter, he also presented him with a gold chain and medallion, in which was set the regal portrait in a circle of diamonds.

The highest distinction with which in those days one could honour an artist was truly earned by Antoon van Dyck, recognized throughout Europe as the king of portrait painters. Presenting human beings was a favourite occupation of our painter from the start. Already aged just 14 we saw him deliver a successful Portrait of an Old Man. The Twelve Apostles, which as a youth he painted on panels at his own initiative, were nothing else than the portraits of his living art friends, like Peter de Jode, whom he adroitly enrobed in historic mantles. Further we see Van Dyck, throughout his life, wherever he visited, appear as the celebrated painter of the portraits of kings, courtiers, magistrates, noblewomen and artists. The person who brought Antoon to portrait painting can be seen in our Sint-Jacobskerk, in the superb portraits of Hendrik van Balen and his wife, painted by this, Van Dyck’s first master. Following Rubens’ example, the young portrait painter began to draw more broadly, to loosen his brushstroke and to colour more powerfully; but fortunately it was not long before he realized that this way of working was not in his nature. The dominant Rubens influenced Antoon primarily as a painter of historical scenes. Van Dyck’s Drunken Silenus, which we saw him paint prior to his direct relationship with the great master, was nonetheless conceived and executed in a Rubensian spirit. It is also easy to see that this creation is not a work of Van Dyck’s own inspiration. It is broadly drawn, powerfully and glowingly coloured; however the shapes, pose and expression, as well as the colour, light and shadow, are unnatural and exaggerated, because the hugeness, the rich fleshy colours and the light effects did not suit our dreamy and poetic Antoon. When Van Dyck entered Rubens’ service to complete paintings of our Jesuit church, he appears to have abandoned even more of his own artistic character. The brushwork of the large church paintings exercised for a long time a fateful influence on Van Dyck’s much simpler, modest way of designing and on his finer brushwork. Many of his history paintings remind us, if not so much in composition and grouping, nonetheless in the figures, strong colours and flamboyant brushwork, of Rubens, who conquered and crazed the young master’s soft heart through his creative power, his natural depiction and powerful, broad painting.

Fortunately, our gifted young man was able to rescue much of his natural inborn quality. Possessing more poetic feeling than wealth of imagination, he therefore abandoned the large creations to paint simple, but heart-moving scenes. He left behind the great master’s huge and powerful approach and went looking for nobility of form and traits, beauty of pose and attitude, and the appropriate expression that reflects the entire soul. In his choice of colours and in his brushwork the same conversion took place. The strong and boastful palette was wisely tempered and made milder; the tones became gentler, the tints more digestible and fused into a natural and enchanting use of colour. His touch became smoother, his brushwork at times so detailed and fine, just as his master Van Balen had preached to him. When Van Dyck travelled to Italy, he was a world-famous master, celebrated everywhere on his art journey, and afforded the honour of painting the portraits of eminent and famous people. These portraits, done during his travels in Italy, are counted among the artist’s best creations. The Venetian masters, whom Van Dyck so deeply admired, exercised an influence on him, but without in any way reforming him. The study of their magnificent creations confirmed his own artistic convictions, and gave the stamp of completeness to his exquisite works. The sensitive and softly brilliant Veronese strengthened his tendency to depict soul-moving scenes with sombre, poetic backgrounds, gave a silver sheen to his already bright colours and added life to his translucent shadows; while the splendid and truth-loving Tiziano gave further warmth to his magnificent light, gilded his beautiful use of colours and added even more natural worthiness to his exquisite figures. In this nobility of conception, in the simple yet noble depictions of his portraits, Van Dyck outdid his predecessors, contemporaries and successors. The tendency to exalt people and things lay in his nature. He himself had, so to speak, an inborn coquetry, which delighted in increasing the pleasantness of beings and forms with rich adornment. He behaved always so nobly, and knew how to distinguish himself in such a way that in the highest circles he was not only tolerated, but even sought after. The most brilliant statesmen, all who were noble and well-off, were proud to take their place in front of the noble artist’s easel; because to have one’s portrait painted by him was to obtain undying fame. The wise painter possessed the secret of having the spirit, the disposition, the entire character of his models radiates in the glistening eyes, the telling facial expressions, lively gestures and natural attitudes of the precisely representing and yet nobility-giving pictures, that he conjured up on canvas with his marvellous palette.

His most famous masterpieces in this area include: the horseback portraits of Giovanni Paolo Balbi and the Marquis of Spinola, in Genoa; Charles I of England and the Marquess of Aytona in the Louvre; King Charles on horseback and Cardinal Bentivoglio in Florence; Thomas of Savoy in Turin; some twenty royal and other portraits in the Van Dyck Room of Windsor Castle, resplendent among them the horseback portrait of Charles I and the portraits of the King and the Queen, Lady Venetia Digby, the Duchess of Richmond, the Royal Children, and Buckingham’s two young sons. Other magnificent portraits in London are Frans Snijders, Philips le Roy and his spouse, Margaret Lemon, the noble poets Thomas Killigrew and Thomas Carew, along with others; in Dresden, Martin Ryckaert and the Children of Charles I; in Vienna, at the Galerie Lichtenstein, Maria Louisa de Tassis and a Cleric of the same family, and in the Belvedere, a Young General in shining armour; in Braunschweig, Lord Stafford; in Madrid, David Ryckaert II, Count Hendrik van Bergh, and the organist of Antwerp’s main church, Hendrik Liberti; in The Hague, painter Quinten Simons; in Brussels, in the King’s Gallery, sculptor Frans Duquesnoy and animal painter Pauwel de Vos, and in Antwerp, in the collection of Mr Ed. Kums: Marten Pepijn. Among all the other art-lovers of our city, we find no excellent portraits by Antoon van Dyck: The Antwerp museum itself owns just three portraits by him: a charming nobleman’s Child, Bishop Joannes Malderus, painted in Rubens’ broad-brush approach, and prelate Caesar Alexander Scaglia, excellently painted in Van Dyck’s own style. The portraits by our famous painter are not, however, scarce. In England, almost every noble family owns one or more family portraits, rendered immortal by the Antwerp master. More than two hundred portraits are exhibited as having been painted by Van Dyck. Further excellent portraits by him are also found in the museums of Madrid, Kassel, Munich, Vienna, Dresden, Braunschweig, Saint Petersburg, Paris, Bordeaux, Florence, Rome, Genoa, Turin, ‘s Gravenhage and Amsterdam.

Amidst his triumph at England’s court, Van Dyck in no way forgot his fatherland. In March 1634 we find him back in his city of birth. On the 28th of that month he purchased a bond of 125 Rhenish guilders on the Manor of Steen, which would become Rubens’ property the following year. The following November, England’s leading painter appeared at the Court of Brussels, where he painted our new governor, Prince-Cardinal Don Fernando.[20] A letter from the Antwerp city secretary Philips van Valkenisse to the deputies of our city in Brussels tells us the Antoon van Dyck was still in our capital city on 16 December 1634. The Antwerp government, which was busy preparing to receive the new governor, asked in this letter “to send as soon as possible a copy of the portrait of the Prince Cardinal, recently done by Van Dyck, currently living at ‘t Paradijs, behind the city hall; in order to use it, in different ways, for triumphal arches, for plays, this being far better than the copies of the paintings already present here, which were made in Spain a few years back by painter Ribbens”. The adroit portrait painter fulfilled his fellow-citizens’ desires: but, when they also requested a portrait of Her Highness Isabella by him, he demanded such a large sum for the same that our Magistraat wrote, on 13 January 1635, that “the price was very excessive” and that instead they would use the copy of a portrait of our late Governess sent from Milan. While Van Dyck was living behind the Brussels City Hall in Het Paradijs, he painted an extended painting, presenting the Magistraat of the Capital City in twenty full-length life-sized paintings.[21] After that, he painted, in Antwerp, a superb Nativity, which is still admired today in the main church in Dendermonde.

Van Dyck had now reached the summit of his glory. The extraordinary honour shown to him by the British king had made him as great and immortal as Rubens in the eyes of our population. Everywhere people admired his paintings, many of which enjoyed the distinction of been committed to plate by our most famous engravers. Antoon himself also handled the etching needle with mastery. His still known and much sought-after etchings are: Tiziano and his lover; Christ crowned with thorns, along with the portraits: Jan Breughel I, Peter Breughel II, Anton Cornelissen, Antoon van Dyck, Desiderius Erasmus, Frans Francken I, Joos de Momper, Adam van Noort, Pauwel du Pont, Philips le Roy, Jan Snellinck, Frans Snijders, Joost Sustermans, Antoon van Triest, Lucas Vorsterman, Pauwel de Vos, Willem de Vos, Jan de Wael and Jan van den Wouwer. These depictions were engraved so painting-like, lively, light and exquisite, that they are still considered some of the best results of the art of etching.[22] While Van Dyck was still in Italy, we already saw him produce portraits of his fellow-artists. On returning to his fatherland, he increased the series considerably and since his stay in England he had added depictions of learned men, statesmen and noblemen, so that the number of his collected portraits climbed to eighty. Most of these creations he sketched on panels, in grisaille or with bistre; others he drew on paper, after which he washed them in India ink. Almost all our best engravers engraved the finest images from these models, which Antoon van Dyck then had printed and published by Antwerp art seller Marten van den Enden.

Before returning to England, Van Dyck received the highest artist’s distinction in his city of birth: the governors of the Schilders-Kamer inscribed him as an Honorary Dean on the list of the governors of the Guild of St Luke. This public mark of homage had been shown also to Rubens, but to no other artist. Our most excellent painters, like Jacob Jordaens, called the honoured man “also the famous and very highly considered artist Antonie Van Dyck”, while others of his admirers named him here the “Chevalier van Dyck”.

Still in 1635, the fêted master must have crossed the sea; because on 6 January 1636 he declares that he is living in London, from where once again he grants a notarized power of attorney to his sister, the Antwerp beguine Suzanna van Dyck. In England’s capital, the king of portrait painters again took up his earlier illustrious social position, and again harvested the most brilliant applause. King Charles I, his illustrious spouse and their noble offspring came and sat again for the Court Painter, to have their portraits painted repeatedly by him. For one of the paintings done at that time, the King Hunting, the famous masterpiece now resplendent in the Louvre, Van Dyck charged the sum of 200 pounds sterling, but the sum was reduced by half by his Majesty, or better by his treasurer. The leading courtiers also vied with one another to be portrayed on canvas by Van Dyck. In the beginning, the master took a lot of trouble to make true works of art of all the portraits commissioned from him, seeking to sound out the characters of his aristocratic models by close company with them. He even invited them to his festive table, to observe their facial features, gestures and attitudes in a relaxed setting. Only then did he pick up his brushes, with which he successfully translated their images so closely and with so much character. The rush of English noblepersons wishing to be portrayed by Van Dyck became so great, however, that the excellent artist had to use a means unworthy of him to fulfil all the commissions. Jabach, one of Van Dyck’s friends who was painted three times by him, related that, for people wishing to have him paint their portrait, master Antoon set in advance the date and hour at which they were to come and sit for him. Van Dyck painted just one hour at a particular painting. As soon as his watch informed him that the time was up, he arose and bowed, as if politely to dismiss the customer. A new guest was immediately ushered in. While the artist modestly received him, the room servant placed another canvas on the easel, cleaned the master’s brushes, and handed him a fresh palette, upon which the regular work began over again. In the first sitting, the essence was captured and the attitude given and sketched. In a quarter of an hour master Antoon drew, on grey paper with white and black chalk, the bodily shape and clothes. Based on these drawings and the clothes, which he asked to borrow, his co-workers and apprentices completed the portrait to the stage that the master needed only to touch them up, while finishing the face to life, after which the hands were painted from those of hired models. In this way, Van Dyck personally spent on some of these portraits, adding all the hours together, no more than a single day. Various painters appear to have assisted him in producing portraits in this way. Those mentioned in this connection include Jan de Reyn from Dunkirk, who had travelled with Van Dyck from Antwerp to London; David Beck from Delft, who had been with the master since his youth, and also Englishmen James Gandy and William Dobson. To these we can also add the Antwerpenaars Peter Bom II, who, according to his own statement, worked for many years with Van Dyck, and Jan Baptist Jaspers, who immediately after master Antoon’s death returned to Antwerp and registered with the Guild of St Luke as a free painter.

It is easy to understand that Van Dyck, with all these assistants and the way he was now working, must have earned large sums of money. However, the court painter spent money as easily as he earned it. The pleasure-loving and carefree artist lived like a born English knight. In playful pleasures and reckless expenditure, he did not intend to be less extravagant than the money-squandering nobility around the like-minded King Charles I. The coquettish and pomp-loving Antwerpenaar constantly adorned himself with such magnificence and taste that the proudest dandies envied him and the most charming ladies admired him. Although still a bachelor, he maintained six footmen and horses and coaches. He himself kept a company of musicians, which rendered his house pleasant with sweet-sounding arias and songs. In his proud and opulently furnished house he gathered everyone elevated in the nobility and everything excellent in the arts and sciences. In particular, towards the beautiful women and exercisers of the dramatic arts the famous master showed himself extremely attentive and generous. To his charming lady friends, his talented fellow-artists and his aristocratic admirers he gave such brilliant feasts, that these were soon spoken of at court.

On a certain day, when the King was sitting for him, while the Earl of Arundel, then Grand Intendant of the Palace, was speaking to him about the country’s finances, Charles I asked his painter: “And you, sir knight, do you know what it is to need three or four thousand pounds sterling?” To which Van Dyck replied “Yes, Sire, a man who keeps his house open for his friends and his purse for his mistresses, quickly sees the bottom of his money chest.” More than his money chest, which was always refilled, Van Dyck’s health suffered from his excessive work, his large-scale carousels and his deeply-felt love affairs, which followed each other in quick succession. To the god of love he sacrificed in particular a considerable portion of his essential life force. He fell head over heels in love with Milady Catherine Wetton, the young widow of Lord Stanhope, who caused our artist much soul-pain, she herself being crazed on Lord Carey Raleigh. Antoon had already conjured up this goddess of his dreams several times on canvas, but she did not long reward him with love and loyalty. To avenge himself of her frivolous approach, the disconsolate lover broke with her by asking an excessive price for one of her depictions, that he threatened to sell otherwise to the highest bidder.

Lady Venetia Digby also, the charming wife of his friend and protector Sir Kenelm Digby, was painted up to four times by Van Dyck, with so much predilection that he must have nursed more than pure admiration for her pretty forms. Once he painted her, on a large canvas, as Prudence, in a long white dress with coloured veil and a jewelled belt. Her pretty hand is stretched out towards two white doves, but a snake winds round her chubby arm. The charming lady is standing on a triumphal chariot, drawn by Deceit, Wrath, Jealousy and Love, blindfolded and with broken bow, strewn arrows and extinguished torch. Above the beauty’s head hovers a group of little singing angels, with the diadem of victory and a banderol inscribed with the words Nullum numen habes, si sit Prudentia[23]. When the attractive Venetia died suddenly, the love-struck Antoon portrayed her one last time, stretched out on her deathbed, with a faded rose next to her, and on the angelic being such a sweet expression as if she was just gently sleeping. Another brilliant woman, whom Van Dyck revered and frequently eternalized with his brush, was Margaret Lemon. However, this love also appears not to have been constant, and the fêted Court Painter sought, between the marble pillars of the Palace, among the ladies robed in lace and satin, once more new food for his unquenchable thirst for love.

Van Dyck’s health was now seriously damaged, and as a result his funds also began to dry up. To prevent his physical ruin and at the same time with the praiseworthy intention of lengthening his glorious life, his close friends, and also Charles I himself, advised him to bind himself in marriage. They spoke to him of a regular way of life, of quiet days, of new art glory and quiet domestic pleasures, and the broken forty-year old bachelor allowed himself to be persuaded. In 1639 he decided to take this important step, from which until then he had diffidently shrunk. His wife was the far from rich, yet aristocratic, Mary Ruthven, the loveliest and youngest companion of England’s queen. The premonition that marriage would occasion him disaster, which had so long weighed heavy on Antoon, confirmed itself. It was as if he sobered up from the long intoxication of love, once he realized all of a sudden that with his sensuous manner of life he had dimmed the lustre of his artistic fame. The constant overhasty painting of portraits to maintain his fortune disgusted him. He went looking for more valuable, greater work, which would enable him to display his full talent yet again. The walls of the King’s banqueting hall in Whitehall, for which Rubens had painted the ceilings, still remained to be decorated, and he proposed himself for completing this important task. The paintings were intended to present the history of the famous English Order of the Garter: the Founding of the Order by Edward III, the procession of the Knights in full regalia, the Solemnity of the Installation and the Feast of St George. These subjects pleased the King so much that he immediately had his Court Painter prepare the sketches. When, however, Van Dyck apprised him of the price he was asking for the artworks, the King, who already owed his painter five years’ pension, and was having difficulty coming by money, hesitated.

With the end of his bachelor life our painter’s lucky star truly disappeared. In 1640 the infamous Cromwell raised his head threateningly in England’s Parliament. The civil war started, and the peace-loving muse of art was forced to leave London. On 13 September 1640, Antoon van Dyck received a laissez-passer to move abroad with his wife. He passed through Holland, where he painted the portrait of poet Constantijn Huygens and his children, on a canvas with the caption Ecce Hereditas Domini Anno 1640, that is now in the museum of The Hague. From there our master travelled to his city of birth, where he could clasp his daughter Maria Theresia, his sisters Suzanna, Anna and Isabella, and some old artist colleagues to his breast.

In January 1641, Antoon Van Dyck arrived in Paris from Antwerp. He had learned that the French king intended to adorn the great gallery of the Palais du Louvre with paintings. With Rubens no longer alive, he arrived full of confidence to present his offer to carry out this major work. Unfortunately, Louis XIII invited Frenchman Nicolas Poussin to exhibit his painting talent in the Louvre, thereby disappointing for a second time our Fleming’s hope of undertaking a major work. The rejection must have deeply affected our sick and yet zealous painter. Maybe the crushing blow had thrown him onto his sickbed, as the proud artist nonetheless remained in the city that set so little store by his talent. There was no point now in returning to London. Charles I himself had to move on 19 March 1641 from his rebellious capital to York, and England’s queen now also arrived at the French court to seek refuge with the French king, her brother. Winter was approaching, and Van Dyck was still sick in the French capital. On 16 November 1641, being in Paris, he wrote to a statesman who had probably proposed to him to paint the portrait of Cardinal Richelieu. “I very much regret the misfortune of my indisposition, which makes me unable and unworthy of such a great distinction. I shall never demand greater honour than to serve his Excellency. Should my health recover, as I hope, than I will make a very special journey in order to receive his orders; I consider myself very obliged; and as my condition worsens from day to day, I am seeking to regain as fast as possible my house in England, for which I beseech you to provide me with a laissez-passer for me and five servants, my coach and four coachmen….” The requested passport came.

With a heavy heart and the pallor of death on his cheeks, our wretched master drove to the nearest seaport, to sail from there to London. Anyone who now saw our worn-out, hopeless artist, and had previously known his lively gaze, his healthy and laughing face, his round neck and puffed-out breast, would have recoiled at the sight of his matte eyes, sunken into the hollow jaws of the bony being, hanging on the now fleshless neck over the fallen-in breast. Scarcely was our invalid carried over the banks of the Thames than he discovered the absence of almost all his artist companions and aristocratic friends, who had fled with the bursting out of the revolution. Already the head, painted by him, of his powerful protector, the minister Lord Strafford, had rolled in front of executioner’s feet. The loneliness and the turbulent days in which the unemployed artist now lived contributed much to further undermining his damaged health.

While he was lying on his sickbed, his wife gave birth, on 1 December 1641, to a daughter, who was named Justina Anna. Three days later the languishing father enacted his last will and testament in the English language. In it he named himself Sir Anthonio van Dyck, born in Antwerp in Brabant, and declared that he was sick in body, but healthy in mind. He entrusted his soul to almighty God and his body to St Paul’s Cathedral in London. All his gold and belongings, that were in Antwerp, except for two letters of credit for 4,000 pounds sterling, he left to his sister Suzanna van Dyck, on condition that she raise his young daughter, Maria Theresia Van Dyck. To his other sister, Isabella van Dyck, he bequeathed an annual income of 250 guilders. All his other possessions, his paintings, letters and papers, with everything that the King of England and others owed him, was to be divided equally between his wife and his legal daughter, recently born in London. To the poor of St Paul’s Church and to the poor of his parish of Blackfriars he left three pounds sterling each, and to each of his footmen and maids twenty shillings. His wife, Mary Ruthven, Mistress Catharine Cowley and Master Aurelius de Meghen, who all stood by his sickbed, were appointed executors of his last will. To the latter he gave 15 pounds sterling, to Catharine Cowley he gave an income of 10 pounds for four years, after which she was to receive 18 pounds a year as the guardian of his daughter, until the latter reached the age of eighteen.

The serious state in which the still so young Van Dyck found himself left a painful impression on his many acquaintances and in particular on the admirers of his unmatched talent. The King, now returned from Scotland, brought his doctor to visit the court painter on his death bed, promising 300 pounds sterling to anyone who could rescue him from death. Arnold Houbraken maintains that various trustworthy persons in London told him of the wondrous attempts made to save the famous Antwerp master’s life. A cow was slaughtered, its entrails quickly removed and the sick man then sewn naked inside it, to warm his blood to enliven the life spirits. It appeared however “that Van Dyck had singed himself on the flame of Cupid’s torch and that the assistants, in cooling this fire, had also extinguished his life fire, so that there was no way of warming him.” With the bitterness of winter, the cooling of the blood increased, and the king of portrait painters died on 9 December 1641, aged just forty-two years, eight months and seventeen days.

Van Dyck’s legal daughter, just eight days old at his premature death, nonetheless inherited a part of her world-famous father’s art wealth. The girl had an ill-fated childhood. Her mother quickly remarried Sir Richard Pryse, but died in early 1645. On 28 April of that year, beguine Suzanna van Dyck gave power-of-attorney, in front of the aldermen of Antwerp, to “Mr Jan Hooff, widower, previously living at the house of the late Antonio van Dyck, her brother, to take possession of and manage, in her name, the possessions falling to Justina van Dyck, aged three years and a half, following the death and absence of her father and mother.” The good aunt requested the appointed person to settle accounts with the stepfather, and to bring up the child under his oversight, or to send the child to her. On 24 November 1649, the aunt enacted a will, in which she kindly remembered Antoon Van Dyck’s bastard daughter. If however “Justina van Dyck, the legal daughter of the above-mentioned late Mr Antoon, living in England were, for the sake of religion, to take up her abode in this country, and were for this reason to be frustrated of her means which she has in England, then she too should receive consideration”. As the orphan did not come over, her uncle, Waltmanus van Dyck, pastor at Minderhout, travelled at the end of September 1654 to London, to fetch his late brother’s daughter. However, in November that year he returned alone, the reason being that Justina van Dyck had, the previous year, when just twelve years old, married Sir John Baptist Stepney of Prendergast, third Baronet of this name in the county of Pembroke.