F. Jos Van den Branden

Deputy-Archivist of the City of Antwerp

Drukkerij J.-E. Buschmann, Rijnpoortvest, Antwerp, 1883

Translated by Michael Lomax, 2018

© Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project.

JVDPPP Note: Van den Branden’s biographical notice on Jordaens is often cited. It remains important owing to the extensive documentation he found in the Antwerp archives. Until now it has never been published in English, only in Dutch, so has not received the wide audience it deserves. It should be noted that Van den Branden refers to Jordaens as ‘Jacob’ throughout. This is a 19th century Dutch version of his name, Jacques, which he did not use nor was he called in the 17th century. It is of course recommended that readers also consult more recent literature. On the whole, however, this comprehensive notice, though infused with a late 19th century art historical slant, has successfully stood the test of time.

Painter-diplomat Balthazar Gerbier was absolutely right when, on 2 June, he wrote from Brussels to London: “Sr. Peeter Rubens is deceased three dayes past, so as Jordaens remaynes ye prime painter here”. Jacob Jordaens was another genial Antwerpenaar, right out of the people’s heart.

His father Jacob Jordaens was a “serge seller”, who, from his marriage on 2 September 1590 in our main church to Barbara van Wolschaten, had lived in the little house “Het Paradijs”, then Hoogstraat no. 13. It was there that our future painter came into the world, to be baptized the following day in Antwerp’s main church. The boy had another two little brothers and eight little sisters, half of whom, however, did not survive long. Our Jacob was a good pupil at school; but then, not yet 14 years old, he declared that he wanted to become a painter. Father Jordaens found the choice a far from bad one. He traded, among other things, in linen canvas, and his son could decorate this with water colours, if he succeeded in becoming a decorative painter. The canvas would then be worth ten times as much, given the heavy demand at the time for painted linen canvas as wall hangings for people who lacked the wherewithal to purchase expensive carpets or very expensive gilded leather.

The permission for the young man to become a painter was therefore gladly given, and in autumn 1607 our Jacob was taken by his father to the studio of Adam van Noort. The wise master quickly discovered the exceptional ability of the sapling placed in his care. He immediately made the apprentice his favourite and soon also his house friend. This latter favour had the effect of stretching Jordaens’ apprenticeship for an exceptionally long period. Master van Noort had an attractive daughter, one of those magnificent, lively women, of the type the painters of those times all dreamed of. Although four summers older than our Jacob, he fell head of heels in love with her. The plump young lady, named Catharina, possessed all the gifts that Jordaens demanded in his wife. She was exceptionally beautiful: her brilliant gaze testified to a warm spirit and a cheerful disposition; she possessed all the qualities to please the man of her choice as a housewife and mother.

Jordaens’ apprenticeship for an exceptionally long period. Master van Noort had an attractive daughter, one of those magnificent, lively women, of the type the painters of those times all dreamed of. Although four summers older than our Jacob, he fell head of heels in love with her. The plump young lady, named Catharina, possessed all the gifts that Jordaens demanded in his wife. She was exceptionally beautiful: her brilliant gaze testified to a warm spirit and a cheerful disposition; she possessed all the qualities to please the man of her choice as a housewife and mother.

After playing apprentice for more than eight years, Jordaens finally left Van Noort’s studio, but taking his master’s daughter with him as his bride. On 15 May 1616, the marriage of the two charming lovers was blessed in the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwenkerk, with Simon Jordaens, the bridegroom’s uncle, along with his father-in-law, acting as witnesses to this religious ceremony. The young couple took up house in the Hoogstraat, in a large rear house with an open yard and entrance through the gate, to the south of the house of a merchant, Nicolaas Bacx, now number 43. This large dwelling pleased our marrieds so well that they already purchased it on 15 January 1618. As they were, however, not yet very well-off, father Adam van Noort took, on the 3rd March of the same year, some mortgages totalling 2,000 guilders on the purchased property. On 16 June 1617, the pretty Catharina gave her fortunate husband a daughter, Elisabeth. On 2 July 1625, she enriched him with a son, baptized Jacob like his father, and who would also become a painter, and on 23 October 1629 their last offspring, Anna Catharina, was baptized. Jordaens’ family was not large, but no less happy for that.

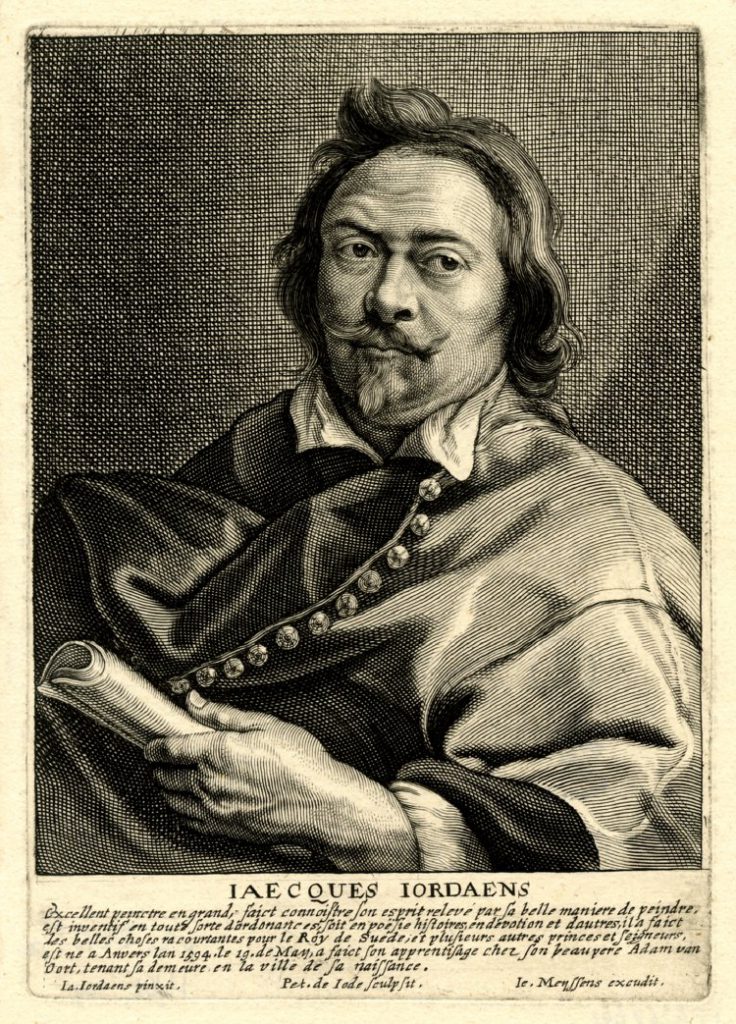

In the same year as his marriage, our artist registered with the St Luke’s Guild as a free master “water painter”. This title, meaning water colour painter, might sound strange for a colourist like Jordaens; but it testifies that our so famous painter exercised the humble profession for which his father intended for him at the outset. In the accounts of the St Luke’s guild, his acceptance as a free master is therefore indicated “Jacques Jordaens, painter, linen merchant’s son”. It is with distemper than he delivered the first proofs of his talent; but in 1620 he was already painting patterns for tapestries, and at the earliest opportunity he would have used a palette, as behoves a true painter. It is asserted that after this time Jordaens took up studies again under Rubens. Ready proofs, however, exist to the contrary. Under Jordaens’ image, engraved during his lifetime from a self-portrait by his artist friend Peter de Jode II, only his father-in-law is mentioned as the master who trained him as a painter. And in truth, Van Noort undoubtedly possessed the qualities that could develop a youthful talent into a successful painter. Moreover, according to the records (Liggere) of the St Luke’s Guild, Jordaens himself received in his studio, in 1620, 1621 and 1623, four apprentices, whom he was required to instruct for three years. In 1626, Rubens, now a widower and a diplomat, left our city, from which he was almost constantly absent for a period of four years. With the return of the great master, Jordaens still received saplings, including the gifted Johan Boeckhorst. The Liggere mention a total of sixteen, but he had many more. On 11 August 1641, we find six in his studio, not one of whom is indicated in the Liggere. These young artists, “all learning the art of painting in the house of Signor Jacques Jordaens” were named: Jan de Bruyn, twenty-one years old; Hendrik Wildens, twenty years old; Hendrik Kerstens, twenty years old; Daniël Verbraken, nineteen years old; Jan Baptist Huybrechts, nineteen years old; and Jan Baptist van den Broeck, eighteen years old.

That Jordaens was so sought after as a master should cause no surprise. Although the city of Rubens had a whole flock of excellent painters, Jordaens was the most original in the choice and development of his subjects. He was the most powerful of our colourists, and it remains significant that he, whose palette even exceeded that of Rubens in richness, never left the fatherland. Jordaens worked in all fields of painting. His greatest glory he harvested from his life-size paintings, recording the life and morals of his day so impressively, naturally and magnificently, as to have remained unequalled. The subjects chosen by the master were taken from Flemish domestic life and from our popular sayings. In particular he delighted in portraying a scene from the well-known Feast of the Three Kings. Which Antwerp burgher does not remember the tasteful and joyful celebration of the Day of the Three Kings, in which straws are drawn and the lot indicates who will wear the paper crown, and who will play the roles of chamberlain, taster, butler, musician, messenger or fool, whilst eating tastefully, conversing spiritly and singly blithely, and each time The King Drinks, the company jubilantly responding with clinking glasses. This joyful hour has struck Jordaens’ life-loving soul, and he transposed it both realistically and magnificently onto the canvas. In the warm chamber, with its brown-wooden panelled ceiling and gilt-leather walls, he depicted, at the richly-laden table, the straight-backed heavy old man, the strong man and the flirtatious young man, next to the charming maiden and the sturdy woman, on whose large bosom a half-naked infant is thrashing about. All these figures were depicted directly from life. The master was an enemy of all sought-for forms of beauty, of all artificiality. He painted faithfully what he saw: the old men negligent, bent, in poor health; the young women busy, healthy and temptingly attractive; the men robust, exuberant, at times wild; everyone in their full character, with the appropriate gestures, with the true expression of their moods on their expressive faces. If the company is grouped somewhat confusedly, the impression is all the more natural. In the bustle of such a lush feast, there may have been little room to move, but there was unrepressed life. Jordaens’ scenes could be rough, but also extraordinarily powerful. With broad, easy brushstrokes he painted warmly, tenderly, powerfully, harmonically, flooding his lusty revellers with a glowing light that makes everything sparkle, imparting ringing life even to the dark backgrounds and heavy shadows. The master’s foremost Festivals of the Three Kings are in the museums of Paris, Vienna, Braunschweig, Kassel, Munich and Lille.

A very well-known saying that Jordaens also liked putting onto canvas was that As the Old Sing, the Young Pipe,[1] in which, sitting comfortably at a richly set table, everyone from grandparents to children at the breast sing and pipe. As this subject was less complicated and calmer, the composition was also simpler and more comfortable, the shapes more delicate and the colouring just as fresh, magnificent and harmonious. His best work based on this saying is owned by Mr de Pret-Thuret in Antwerp. Other versions by Jordaens of As the Old Sing, the Young Pipe are conserved in the Duke of Arenberg’s gallery in Brussels, in the Louvre in Paris and in the museums of Dresden and Berlin.

Starting from another popular saying, Jordaens censured men with two faces, in his presentations of Peasant Blowing Hot and Cold at the Satyr’s Table. This is a subject that he evidently put to canvas with pleasure, as examples are conserved in the museums of Brussels, Kassel, Munich, Saint Petersburg and London.

That Jordaens was an excellent portraitist is already proved in his moral scenes, which in fact can be seen as groups of family portraits painted from life. His real talent as a portraitist is clearly visible in his splendid depiction of naval hero Michiel de Ruyter, which hangs resplendent and full of character in the Louvre. In the Uffizi Gallery in Florence hangs the portrait of Jacob Jordaens, painted masterfully by himself. Equally splendid is the picture of his wife, Catharina van Noort, whom he presented as a sturdy maid with a parrot, and of which the English Lord Darnley owns the original and Earl Fitzwilliam a repeat. The Kassel museum exhibits a Group of Portraits, deemed incorrectly to be the individual members of his own family. The Madrid museum also conserves a Group of Family Portraits in a Courtyard and Two Singers with a Clarinet Player painted by Jordaens. Resplendent in the museum of Valenciennes is a canvas by him with two very sweet Children’s Portraits. In Saint Petersburg are various of his individual portraits. Dresden owns, from his hand, the servant of our St Luke’s Guild, Abraham Grapheus; Braunschweig, A Bearded Male Head; Rouen, an Old Man, and our own Antwerp museum the Portrait of a Lady, and in private collections in our city one can admire other excellent Portraits, which we owe to Jordaens’ brush.

In religious paintings, Jordaens did not attain the heights that he achieved in the above-mentioned areas. To excel in sacred history, he lacked the essential quality: uplifting of the soul or inner religious feeling. At times he glorified the Saviour with a pleasant form and impressive appearance, but his treatment of the saints was often far from respectful. He, who in his popular painting created so many dainty female figures, painted in his church works much coarser figures. One of Jordaens’ most prominent religious pictures is the Last Supper, which he produced for our Augustijnenkerk and which is now displayed in our museum. In the Christ we still discover a degree of divine worth, but not only Judas has an exaggeratedly repugnant being, but also the good and wise apostles, the announcers of peace and love between people, turn under Jordaens’ brush into coarse, everyday fellows, or rather Hercules, inculcating fear rather than respect. Lacking uplifting of soul and depth of feeling, Jordaens tried to make his creations awe-inspiring through their physical size. For this reason he treated his sacred subjects almost as if bragging about his art, and to the free flourish of his bold and powerful brush he sacrificed nobility of form. In his church paintings he also makes the least wise use of the richness of his palette. The former watercolour painter now dipped his brushes at times so deeply in the strongest hues of his oil paints as if to blind the spectator. At times, he played marvellously with the most opposing colours, at other times, on dark backgrounds and in heavy shadows, he extinguished the exaggeratedly powerful colours of his grossly folded draperies and the almost glowing flesh colours of his huge by the brightness of his always warm and magnificent light. In his colouring and his lighting, Jordaens was always sublime, poetic; but otherwise he remained a proponent of painting people simply as they were. For this reason, his best religious paintings were those closest to real life.

The Louvre owns a large canvas of his Christ Driving the Sellers out of the Temple: with well-captured characteristics and types of usurers and saleswomen fleeing in natural haste with their goods and animals from the stick of the indignant Saviour. In our Antwerp museum hangs an Adoration of the Shepherds by the master, in which everything is presented naturally, simply and cosily. This was also one of Jordaens’ favourite subjects. We find his Adorations of the Shepherds in the Lichtenstein Gallery in Vienna, and in the museums of Frankfurt, Braunschweig and Mainz. Our city also has, by Jordaens, in the Terninck school, a Christ on the Cross and in the beguinage church, a Deposition, which can be included among the master’s best church paintings. Our Sint Jacobskerk owns a Saint Carolus Borromeus in Prayer for the Plague Sufferers of Milan, the Augustijnenkerk the Martyrdom of Saint Apollonia; the Sint Pauluskerk a Crucifixion, and our museum the Burial of Christ and the Nuns of the Charitable Hospital. In the Saint Nicolaaskerk in Dixmuide hangs a superb Adoration of the Magi, signed I. IORDAENS 1644. Jordaens painted for our churches and monasteries a number of paintings, which since the French occupation have gone missing or have remained in France. Thus we find in the museums in Lille, Christ and the Pharisees; in Rennes The Woman Taken in Adultery; in Lyon Mary’s Visit to Elizabeth and Christ’s Birth; in Marseille The Miraculous Catch of Fishes; in Rouen Jesus at the Home of Mary and Martha, and in the Eglise Saint-André in Bordeaux, the Crucifixion. Others of his church paintings, conserved in museums, are: in Brussels Saint Martin Healing a Possessed Man, marked I. IORDAENS FECIT A; 1630, in Ghent, Saint Ambrose and the Adulteress; in Tournai, a Calvary; in Paris, The Last Judgement, signed I. IOR. DEC 1653, and the Four Evangelists; in Dresden, the Search for Christ’s Body in the Grave, and the Presentation in the Temple; in Main,z Jesus among the Doctors and the Last Supper, in the Galerie Schleissheim near Munich, the Twelve Year-Old Christ in the Temple, the Holy Family and a Saint Jerome; in Braunschweig, Christ with the Disciples at Emmaus and the Crowning of St Joseph; in Copenhagen, Jesus Blessing the Children; in Madrid, the Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine, Jesus and St John as children next to a fountain, and in London, the Holy Family.

Works by Jordaens on older historical subjects are not numerous, but in this field he left one major masterpiece, which is exhibited in the Madrid museum. This is a Judgement of Salomon, which is outstanding not only for the magnificence of its colouring, but also the beauty of the drawing. Dresden has in its museum a Diogenes by Jordaens, with the philosopher searching with a lantern at midday in the market of Athens for a man, and the Prodigal Son at the pigs’ trough, a repeat copy of which by Jordaens hangs in the museum in Lille.

As a painter of symbolic works, Jordaens similarly produced a superb work. This is his signed canvas in the Oranjezaal of the Huis ten Bosch. People who did not value his scenes of daily life at the full value considered this, unjustly, as his very best work. Be this as it may, it remains a major masterpiece, one of the most imaginative compositions, rendered magnificent by the superb colour and the very powerful lighting. It was painted in 1652, at the expense of Amalia van Solms, who wanted to extol her late husband. It depicts the Triumphal Entry of Prince Frederik Hendrik of Orange, carried in a golden carriage drawn by four white horses, and surrounded by mythological and symbolic figures, warriors and people. Above this most splendid item in the Oranjezaal, Jordaens painted another remarkable work, depicting Time mowing down Slander and Vice, while bony Death smashes Jealousy’s throat. The Brussels museum has two superb symbolic works by our master: Fertility and Earthly Vanity.

For designing his mythological pictures, Jordaens took the grand master Rubens as an example. At times he copied his work, as with his Drunken Silenus with the Bacchantes and Satyrs in the Dresden museum, and Venus and Cupid Concealed in the Grotto, in the museum of The Hague. In this area, Jordaens equalled Rubens’s example in richness of colour and fleshiness, but was at times less fastidious and tidy with his shapes. Magnificent and famous is his Jupiter Fed by the Goat Amalthea, in the Louvre, with the goat being milked by a naked woman in the presence of a satyr. Equally famous is Jordaens’ Education of Bacchus from the museum in Kassel and Meleager and Atalanta in the museum in Madrid. Displayed there also are Homage to Pomona and Diana Bathing with a background of superb buildings. Conserved in other museums are: in Amsterdam, a Satyr, sitting against a tree and playing the flute to a goat, two sheep and a ram; in The Hague, a Forest God with Nymph; in Dresden, Ariadne Surrounded by Fauns, Satyrs and Baccantes, Silenus with Drinking Bowl Filling a Bacchante, and a Satyr with Fruit Basket next to a Maid; in Kassel, a Bacchanale; in the Galerie Schleissheim, a Drunken Silenus with Satyrs; in Vienna, in the Belvedere, Jupiter as a Guest of Phileon and Baucis, and in the Galerie Lichtenstein, The Drunken Silenus, Satyrs, one of whom is pressing grapes next to a female panther with her young, and Mercury and Argus; in Stockholm, The Sleeping Chamber of King Candaulus; in Saint Petersburg, Argus Dozing Off; in Florence, Venus with Mirror Surrounded by the Three Graces and Neptune bringing a horse out of the earth, while Galathea embraces Cupid in a triumphal chariot; in Rennes, Nymphs and Satyrs, and in Lyon, a Drunken Silenus. In these mythological pictures, Jordaens at times painted excellent landscapes and from time to time an attractive building; he placed pretty flowers and fruits in his bacchantes’ hands; he enriched his canvases with attractive domestic animals or cattle, and from time to time painted proud horses and superb wild animals.

In various foreign museums and in private collections in our and other cities, are further artworks by Jordaens. However, we believe that we have already mentioned sufficient to confirm that he was both a diligent and excellent master.

Even if the tapestries made to his patterns no longer exist, we have to point to some of his masterworks in this area. The applause he gained for his popular scenes enabled him to have similar works woven in tapestry form. On 22 September 1644, our painter committed to Frans van Cophem, Jan Dordijs and Boudewijn van Beveren to provide them with patterns for a “chamber tapestry, with figures, viz. certain chosen Sayings, which he, Signor Jordaens shall consider suitable, at 8 guilders each”. In those days there hung, in Antwerp, in the chambers of Signor Carlo Vinck, superb tapestries including gold thread, depicting Large Horses, based on the patterns of Jacob Jordaens. These patterns were sent on 5 July 1651 by Antwerp tapestry merchant Frans Smit as samples to Hamburg with the following description: “Item two paper patterns of Actions of Horses, painted by Jordaens, the one eight rolls in size and the other nine rolls, for six hundred guilders each”. Another Antwerp merchant, Jan de Backer, was jealous of these awesome wall decorations. On 18 November 1654, he too ordered from Brussels tapestry makers Hendrik Reydams and Everaard Leyniers “a chamber of fine tapestry, Brussels work, of seven pieces, six ells deep, of Large Horses, based on the pattern painted by Jordaens, containing in total three hundred and sixty ells, of similar virtue as a chamber, made after the same pattern, and delivered to Signor Carlo Vinck on 30 July 1652.” However, this work would be without gold thread, and the price was set at 16 guilders per square ell.

Jordaens was also a talented etcher. In addition, his paintings were transferred to plate by our leading engravers. As if carried on the wings of the wind, Jordaens’ artistic fame spread everywhere. Commissions arrived not only from the widow of the Dutch stadhouder, but also from the kings of England and Sweden. Along with Rubens and Van Dyck, Jordaens was the Antwerp painter who earned the most applause and whose talent had to be rewarded the most generously. Our artist himself set this pay quite moderately. On 23 February 1644, he declared to have been away from home for three days on a journey to Brussels, and charges for this disturbance “twenty guilders a day for his artistic painting”. For food during the journey he charges 4 guilders 16 stuivers a day. In fact he generally earned double what he charged here. This appears in a commission that he carried out for The Hague. On 21 April 1648, Johan Philips Silvercroon came to Antwerp, for himself and on behalf of Hendrik Hondius, resident in ́́́΄s Gravenhage, to commission a total of thirty-five paintings from Jacob Jordaens. The subjects of these were to be determined in a memorandum by the commissioning parties and the artist. The canvases were to be 3 ells and 1 ½ quarters wide and 4 ½ ells and half a quarter high and to be foreshortened, suggesting that these were ceiling pieces. According to the notarial deed, our artist was required “to paint the paintings partly himself and partly have them done by others, as most convenient for him Jordaens. And the work painted by others he was to overpaint in such a way that it would be taken to be Signor Jordaens’ own work and accordingly to place his name and signature under it.”

All thirty-five elongated paintings were to be completed “within a year and no later than 1 May thereafter”. They were to be delivered in The Hague to the above-mentioned Silvercroon and Hondius, who would pay 80 Flemish pounds for each item, or 2,800 Flemish pounds for the complete series. Converted into guilders, this amounts to 16,800 guilders, which Jordaens was to receive for a single year’s work. In this way, he earned just over 46 guilders a day. To produce thirty-five large paintings in a single year shows how inventive a composer and skilful a brush-wielder Jordaens must have been. As we have shown, measures were taken, however, to ensure that he himself painted the important works. This was also very necessary. Jordaens worked à la Rubens in his own way. He too found fellow-workers among his pupils whom he had transfer his sketches onto canvas, after which he would, with the final brushstrokes, impress his own characteristic stamp on them. Through our investigations we have been able to recognize how our painter at time produced his works. On 25 August 1648, he himself says that the five paintings he sold two years earlier to Signor Martinus van Langenhoven “were painted, repainted and altered entirely by his own hand”. He admits to having previously treated the same objects; but as they were ordered, so he would paint them again. To save time, he had copies made of these first designs, which he improved where he was displeased with them, and added to them where he deemed necessary. In this way, he says “he has changed them, and painted, overpainted and repainted all with his own hand, in such a way that he Jordaens considers them to have been done by him, as good as his other ordinary works, viz. As the Old Men Sang and Candaulus. The Argus and the Vulcan he began from the start.”

If, in his ripe age, our artist was able to accumulate wealth, at the beginning of his career his income was nonetheless low. We find this confirmed as follows. Jordaens was appointed Dean by the following decision of our Magistraat (city government): “Committed and ordered Jacques Jordaens to be Dean of Saint Luke’s Guild in this city, subject to the proper oath, and that for the present year. Actum in Collegio 28 Septembris anno 1621.” The then resigning dean had placed the guild heavily into debt. It had been expected that the city government would approve an increase in the income; however, as we saw, this proposal was rejected on 12 February 1621. As a result, it would be impossible for the new dean to cover the expenditures already incurred with the low income. As Jordaens himself was not well-to-do at the time, he opposed running into debt in this way. He went to the Magistraat and explained verbally why he wished to be spared the deanship. Our lawmakers were not, however, accustomed to rescinding a decision that had already been taken. Jordaens from his side insisted on the impossibility of governing the Painters’ Chamber without the requested increase in income. Seeing that the Gentlemen were unwilling to give way, he left the College, without taking the required oath. The extent to which this impertinence embittered our Burgomasters and Aldermen is shown by their following decision: “Again orders Jacques Jordaens, within twenty-four hours of the delivery of this summons, to come and take the oath as Dean of the Guild of Saint Luke, in this city, on pain of one hundred guilders, to be paid as per the old custom. Actum in Collegio 30 Septembris 1621.” As soon as our painter had received a copy of this harsh warning, he grabbed a pen and repeated in writing that he was unable to take responsibility for debts incurred by others. He was prepared to undertake the service of dean, and also to cover the expenses incurred during his deanship; but that, to avoid any misunderstanding at a later date, requested a declaration from the Magistraat that he was making the oath solely under this condition. On 1 October 1621, the City accepted this proposal, and from then on Jacob Jordaens fulfilled the role of co-dean, until 10 September of the following year, when suddenly Antoon Goetkind was appointed Senior Dean and Abraham Goyvaerts Co-Dean.

Shortly after Jordaens had refused to serve as Senior Dean, his artistic fame became established, and his financial position improved substantially. On 16 June 1633, he shared his parents’ estate with his brother Izaäk, his sister Anna[2], the wife of Zacharias de Vriese, and his sisters Magdalena and Elisabeth, both beguines. From the inheritance he obtained, on 18 March 1634, his birth house “het Paradijs”, and on 10 March of the following year he purchased a further two houses on the Verversrui. On 11 October 1639, Jordaens also purchased from merchant Nicolaas Bacx the large house “de Halle van Lier of Turnhoutsche Halle” at Hoogstraat 43, in front of the rear house that he was living in. He then had both front and rear houses demolished to build there, to his own plans, a residence worthy of the palaces that Floris and Rubens had erected for themselves. In undertaking his building work, Jordaens encountered much unpleasantness from his neighbours, the merchants Melchior Oostering and Frans Rijssels. The legal battle over party walls and provision of light lasted from 1640 to 1649. In the meantime, the masons were hard at work; because on the west wall of the inner courtyard a memorial stone was to be placed mentioning the year 1641. Of the proud bluestone gables, which Jordaens erected in the Flemish building style of his day, only two remain in the large square inner courtyard. These are the rear wall of the dwelling and the front wall of the master’s large studio building, both of which were committed to engravings and witness to both Jordaens’ artistic taste and his wealth.[3] On the inside, he decorated his large halls and numerous rooms with sculpture, tapestries and tasteful furniture. For the two back rooms to the south giving onto the courtyard, he produced ceiling paintings, presenting: The Twelve Apostles, The Twelve Signs of the Zodiac, Suzanna with the Elders, Olympus, the Offering to Apollo, a Muscular Man in the Clouds with a naked Woman on his Shoulders, a Dying Child whose thread of life is being severed by an Angel, a Venus with the God of Love, Cupid fleeing a naked Woman, Little Gods of Love with Flower Garlands and Little Gods of Love with Fruit Garlands.[4]

Jordaens, the fêted creator of so many a large and magnificent painting, was also physically the man to live in such a proud and colossal building. Look at his portrait, painted by himself and engraved by Peter de Jode II. He demands respect, with his magnificent, sturdy head with its rough hair, which appear to be carelessly put in place with the fingers. Under his large forehead sparkle eyes in the spirited brightness of which it would be difficult to mirror oneself for any length of time. His broad-winged nose and his tightly closed mouth, above which the rough hair moustaches are drawn upwards, testify to determination. Just one of his hands is visible: but their strongly developed joints show that Jordaens could as well have wielded a smith’s hammer as a paintbrush. His broad shoulders are covered, into his short and fleshy neck, by a wildly folded coat. Were he to open this, one would see a pair of muscular arms which could, if necessary, enforce respect. Jordaens’ disposition matched his appearance. On one occasion, his physical strength and boldness served him well: the wife of silversmith Van Mael was enraged against the Jordaens family, although the latter declared that she “never knew Van Maels or his wife and had never exchanged words – good or bad – with the same”. At around one o’clock on Saturday 26 July 1642, this Mrs Van Mael was leaning over her under-door in the Hofstraat, when Jordaens’ wife passed. Without the latter saying or doing anything amiss to anyone, Mrs Van Mael began scolding and threatening her. The fact that she did not immediately attack her was because she was not totally recovered after childbirth. But she shouted at Jordaens’ wife “Wait till I’m free, and I’ll catch you and give you a pair of black eyes and a thick nose!”. Two days later, she indeed appeared in the Hoogstraat to execute her threat. It was like a regular attack on Jordaens’ family and dwelling. The violent act must have been carried out with forethought, because the silversmith’s incensed wife came at dusk, supported by various male persons. As was then the custom in Antwerp on summer evenings, Mrs Jordaens was sitting peacefully in front of her gate chatting with her daughter Elisabeth, her sisters Anna and Elisabeth van Noort, the fifty-year-old Perijne Caesen and the sixty-year-old Anna van den Bogaert. There came all of a sudden Mrs Van Mael with her husband and his assistants. She placed her newly-born child on the ground, grabbed a knife, and shouted: “Here the whores are sitting. I’ll cut their faces to pieces.” Mrs Jordaens sprang up, fled indoors with her sisters and closed the door tight. Unfortunately, in their haste, Jordaens’ daughter was shut outside. She was heard shouting for help, amidst the scolding and threats of the attackers. Mother Jordaens realized the terrible situation. Undeterred, she opened the door again and shot outside to bring her daughter out of danger. She succeeded, but at the same time the furious silversmith’s wife jumped inside the house “shouting and screaming: I’ll cut her neck off”, the which horrible cry was repeated by Van Mael, who was following his other half. In this frightful moment, Jordaens came hurrying to the rescue, and his physical strength provided protection against the danger threatening him and his family members. As the armed Van Mael continued to shout to the outside that he would “wait for and kill Jordaens and the members of his family”, our artist submitted a written complaint about this act of violence to the Magistraat. Already on 30 July 1642, the city government placed the matter into the hands of the public prosecutor, and in the meantime Van Mael and his wife were forbidden “to say or do anything amiss against Jacques Jordaens, his wife or family in any manner, directly or indirectly, or to enter their house, on pain of any measure as may at the time be deemed appropriate in the circumstances.”

Whether the public prosecutor’s office avenged the desecrated dwelling or the dishonoured Jordaens family, we have been unable to discover. Nor have we been able to track down the real reason why our painter and his family members were set upon so violently. That the reason lay in his changed and much talked-of change of confession cannot be confirmed. The fact is that Jordaens was in relations with the Protestant Northern Low Countries long before receiving the major commission from The Hague. Already on 25 September 1632 he had confirmed the identity of his sister-in-law Elisabeth van Noort, the young daughter, “who requested passage in order to travel to Holland, in conformity with the passport of Her Majesty of 29 June 1632 last, obtained by Adam van Noort, for himself, his wife, son-in-law and the above-mentioned young daughter”. Thus, from that date Jacob Jordaens had a laissez-passer to travel to Holland. He also made use of it on various occasions. It is certainly in this way that he came to favour the house of Orange in terms of nationality and religion. Nor was he alone. While at the end of the 16th century, following the closing of the River Scheldt and the ban on Reformed worship, more than half of the population of Antwerp had decamped; in the 17th century our city was still swarming with Protestants or Holland-minded people. Their number was so large that, in 1622, with the Orange army approaching, the defence of the city’s five land gates was taken from the citizen watches and entrusted to the religious of the male monasteries and the Jesuit paters; while on higher orders Walloon soldiers replaced our citizen watches for guarding the Slijkpoort. Then again secret preaching sessions were held, attended by hundreds of men. In the night of 24 December 1624, all the streets were closed off by soldiers and the houses searched to seize the weapons which could have been taken up to unite the Low Countries which were then falling apart. In 1625, new conspiracies were discovered, and eighty Reformed families were forced into exile. On 9 August 1629, the city government deemed it necessary to forbid, on pain of death “making scandalous proposals against the Holy Church or His Majesty”. On 5 September, it requested permission from Her Highness to be allowed to banish from the city “persons who are notoriously heretic and turbulent”. On 24 October, she ordered that only good Catholics be included in the city watch, and, on 20 December of the following year, Mr Willem Bolognino, pastor of our Sint Joriskerk, was honoured with 100 guilders for dedicating to the Gentlemen of the Magistraat his work “Clear repudiation of the supposed ancient nature of the Calvinistic faith”. The entire neighbourhood in which Jordaens lived was, in 1635, suspected of Protestantism and of pro-Holland feeling, so as to be openly scolded for this from the pulpit. Jordaens declared himself, at least publicly, not a Catholic only years later. One of the visitors to his studio was the then well-known prelate Caesar Alexander Scaglia. This zealot of the Roman Mother Church would certainly not have stood on a confidential footing with any enemy of the faith, and he remained favourable towards Jordaens. It is true that, when Scaglia died on 21 May 1641, our painter was still working on five paintings for him. Articles 18 and 19 of the Treaty of Munster gave the reformers in our country a place of burial and they were permitted to exercise their religious confession “with due decency”. However, this agreement between our monarch and the States of the United Netherlands was, at least for our natives, quickly violated. Jordaens appears now also to have come under suspicion for being overly involved in matters of state or conscience. If our suspicion is unfounded, we do not understand why on 23 July 1649 he “maintained, swore and affirmed, by oath and of his own free will amicably to God and his Saints, that it is true, that he, last May, was in Brussels, with his son, for no other purpose than to pay the report money for the proceedings he had against Franchois Rijssels.” Up to six years after that, Jordaens continued to work for the Catholic places of worship.

The painting of Saint Carolus Borromeus, in our Sint Jacobskerk, carries, alongside his signature, also the figures 1655. On 5 May of that year, a placard of the King ordered the strict persecution of the “ministers and preachers of the pretended reformed religion” who came here to spread “their heresies” in clandestine gatherings, while our compatriots attending the sermons were to be treated “with full rigour”. At that stage, Jordaens broke openly and courageously with the church in which he had been baptized and married. Also, the reformers were now so embittered by the persecution they had suffered that they plucked up the courage to disseminate their fundamental principles in print within the Antwerp city walls. This fact caused a great commotion. On 25 August 1655, the College of Aldermen decided that “given that certain books with a geuze-catechism have been disseminated in this city, we order that one hundred guilders be given to the person denouncing the author of this deed”. The next day, this Judas wage was announced by public placard. Whether it was this bait that brought the disseminator of this geuze-catechism into the claws of the court is not recorded. However, the public prosecutor’s office includes in the receipts in its book of accounts from 1651-1658, on folio XI, this significant item: “For the fact that painter Jordaens had written certain scandalous writings, satisfecit 200 pounds and 15 shillings.”

This heavy fine did not bring our painter to repentance. On 16 December 1660, he gave an oath, as witness, in the Protestant manner, not on the Saints, but solely on God.[5] Although condemned as the author of “scandalous writings”, Jordaens did not forfeit the respect of his art colleagues, as he remained constantly in close and good relations with the Guild of Saint Luke. On 14 August 1665, he donated to the Painters’ Chamber another three ceiling pieces, which now hang in our museum. These are: the winged horse Pegasus, whinnying away from Parnassus, Commerce and Industry, which protect the Fine Arts and Human Law based on Divine Law and marked ARTI PICTORIAE IACOBUS IORDAENS DONABAT. On the latter elongated canvas stand Aaron and Moses with the stone tablets, on which Jordaens wrote these words: “Interrogate your brothers justly and judge equally your brother and the stranger. You shall not act unjustly. In court, do not reject the person of the poor, nor be affected by the impression of the mighty. Give judgement justly to your fellow being.” When these artworks were attached to the ceiling of the Painters’ Chamber, they emptied there with “Mr Jordaens” a good cup of wine. Thereafter, the generous artist was honoured with a silver lamp with bowl worth 336 guilders, while verses of effusive praise were read to him.

The Jordaens honoured in this way was still a member of the Reformed confession. Despite the royal ban, following the conclusion of the Treaty of Munster, a Calvinist parish had been founded in Antwerp, under the title of “the Brabant Mount of Olives”. Jordaens became a zealous member of this church, in the lap of which his beloved wife also died on 17 April 1659. His daughter Anna Catharina must similarly have belonged to the Reformed community, because she married the Jansenist “Lord and Master Johan Wierts, Councillor in the Council of Brabant in ‘s Gravenhage.”[6]

However, the existence of the Mount of Olives was forbidden by the king, and for this reason its members lived essentially as a “repressed community”.[7] The persons belonging to this institution kept this strictly secret. The only persons accorded access to their divine services were those of whose uprightness in matters of belief the others were convinced. A certain “Dutch Mary”, who had attended some of the meetings as a maid, fell away from the community and, to make things worse, entered the service of the choir dean of the main church. From this time onwards, the members of the Mount of Olives did not dare to meet in the same place twice in a row. In 1671, Jordaens, with his daughter Elisabeth and his two maids, took part in the “holy and venerable Communion Service” held in the house of one of his fellow confessionalists. On 14 December 1674, our painter, in turn, made the rooms of his superb residence available to his persecuted Calvinist-minded friends. From then onwards, several further meetings for divine service were held in Jordaens’ house. 16 June 1678 was the last time that he opened his door for them. On 18 October of the same year, the famous artist was affected by the terrible “sweating or Antwerp sickness”, and in the same night he died, together with his daughter Elisabeth. The bodily remains of both were taken over the Dutch border to the little Protestant church of Putte and buried there, under a single tombstone, with the commemorative inscription:

HERE LIES BURIED

JACQUES IORDAENS PAINTER,

DIED IN ANTWERP ON

18 OCTOBER A° 1678,

AND

THE HONOURABLE CATHARINA VAN OORT,

HIS WIFE DIED ON

17 APRIL A° MVI C LIX

AND

MISS ELISABETH IORDAENS,

HER DAUGHTER DIED ON

18 OCTOBER A° 1678.

CHRIST IS THE HOPE

OUR GLORY[8]

[1] The painting mentioned here ‘The Old Folks Sing, the Young Folks Chirp’ by Jacob Jordaens, was purchased at the beginning of 1883 for the Antwerp museum for 50,000 francs.

[2] When this Anna Jordaens died, on 25 May 1668, her estate included an attractive collection of paintings, including: a chimney-breast piece “The King Drinks by Mr Jacques Jordaens, a Fool in the manner of Mr Jordaens, and two items of painting in the manner of Mr Jordaens, the one a Paul and Barnabas and the other a Demitte”, (A Christ dying on the Cross).

[3] See the Historisch album der stad Antwerpen door Jos. Linning, met historische aanteekeningen door F.H. Mertens, Antwerp, 1868.

[4] The last eight canvases still belong to the owner of the Jordaens House, Mr Karel van der Linden-Rijmenans, who has transferred the works to his new dwelling at Mechelse Steenweg 70 in Antwerp.

[5] Juravit tantum per Deum. L. GALESLOOT: Un procès pour une vente de tableaux attributes à Antoine Van Dyck, in Annales de l’Académie d’Archéologie, Antwerp, 1868, p. 601.

[6] This born Antwerpenaar, who in 1640 studied at the University of Leuven, later became chancellor and subsequently president of the same Council of Brabant. He left as children of Anna Catharina: Lord and Master Joan Jacob Wierts, Member of the Council and Auditors’ Office of his Royal Majesty of Great Britain in ‘s Gravenhage, and Suzanna Catharina Wierts, who married, first Lord and Master Joan Andries van der Meulen, Lord of Nieucoop, a councillor of the Sovereign Council of Brabant and Dijkgraaf of the countries of Vianen, and subsequently Mr Anthonis Slicher, Councillor ordinaris in the Court of Holland, Zeeland and Vriesland.

These sole grandchildren of our painter were in this way persons of rank and also very wealthy. Only on 7 July 1708 did they sell, in Antwerp, the magnificent house of their maternal grandfather. And his remarkable collection of one hundred and eleven paintings, including forty-four from his own hand, was auctioned only on 22 March 1734 in ‘s Gravenhage.

[7] P. GÉNARD: Notice sur Jacques Jordaens (in Messages des sciences historiques), Ghent, 1852, p. 215

[8] In 1794, the little church of Putte was demolished by the French, and Jordaens’ tombstone broken into three pieces. In 1829, Antwerp merchant Frans Pauwelaert discovered the desecrated gravestone, the two main pieces of which, pulled out of the rubble, were placed together so that the entire inscription remained legible. A facsimile of this gravestone was then made, which appeared in 1833 in the Messager des sciences historiques with an article by Mr Norbert Cornelissen, who issued a call to repair the grave marker of our famous painter. In 1844, our city government requested permission from the Dutch government to repair Jordaens’ gravestone and to set up a memorial plaque to him in Putte. But already the following year, King Willem II had the gravestone reconstituted and surrounded with an iron railing. Today the tombstone is set up in a bluestone base with caryatids, painters’ equipment and laurels, above which sits a bronze bust of Jordaens. Carved into the base are the words “This memorial, set up by a commission of Belgians and Dutchmen, in memory of J. Jordaens, A. van Stalbemt and … from the contributions of the Antwerp municipal government and of mainly art lovers, was unveiled on 22 August 1877, during the festivities in Antwerp to mark the 300th anniversary of Rubens’ birth.”