Ludwig Burchard, ‘The Early Work of Jacob Jordaens’, first published as ‘Jugendwerke von Jacob Jordaens’, Jahrbuch der Preussischen Kunstsammlungen, XLIX, 1928, pp. 207-18, translated by Beelingwa, edited and updated by Joost Vander Auwera, Justin Davies, James Innes-Mulraine, with an introduction by Joost Vander Auwera.

How to cite: Burchard, Ludwig “The Early Work of Jacob Jordaens” In Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project. Edited and updated by Joost Vander Auwera, Justin Davies, James Innes-Mulraine, with an introduction by Joost Vander Auwera

http://jordaensvandyck.org/article/the-early-work-of-jacob-jordaens-by-ludwig-burchard/ (accessed 12 March 2026)

Dr. Joost Vander Auwera

The youthful work of a painter is often the part of his or her oeuvre which is most difficult for art historians and admirers to grasp, as a young artist moves quickly from style to style before finding an artistic identity of his or her own.

This is certainly the case with Jacques Jordaens (1593 – 1678), as was rightly remarked by the great Jordaens scholar the late Roger – A. d’Hulst in his seminal 1982 monograph on the master. a On the other hand, it is often that art historical discoveries from youthful periods can still be made, and where unpublished artworks that remained under the radar of a more established later style can still pop up: the case of Rembrandt is a telling example of that exciting phenomenon.

This 1928 article by the reputed Rubens scholar Ludwig Burchard, b originally published in German, was the first on the formative years of Jordaens after Paul Buschmann and Max Rooses laid the foundations of modern Jordaens research with Buschmann’s monographic exhibition on the master in 1905 and Max Rooses’s 1906 Jordaens monograph.c It would be more than two decades later before d’Hulst could complement Buchard’s findings in several articles in which he tried to establish a more precise chronological order for the growing corpus of the artist’s youthful works.d It is a testament to Burchard’s connoisseurship that all studies on the young Jordaens that have followed this important 1928 article have complemented rather than corrected Burchard’s groundbreaking scholarship. It is with great pleasure that we have translated the article from the original German in order to make it accessible for the widest possible audience. We have also incorporated 29 colour images of the paintings mentioned in the text. The 1928 article contained only nine black and white images. At the same time, we have traced all the paintings and their locations in 2020, nearly 100 years later.e

It may seem surprising that a Rubens specialist like Ludwig Burchard showed some particular interest into Jordaens but one should not forget that back in 1928 the precise borderlines between the oeuvres of Rubens and Jordaens were not yet as clear-cut as they are today. For example, Jordaens’ Christ and Nicodemus was acquired by the Brussels museum in 1906 as a Rubens – only one year after Buschmann’s exhibition and the same year as Rooses’ monograph. Another telling case of the lack of familiarity in those days with Jordaens’ youthful hand, discussed here in detail by Burchard when rightly attributing that early painting to the master, is the Holy Family in the same museum, which had been attributed to Abraham Janssen and then to Pieter van Mol.f

Moreover, one of Burchard’s very last articles, completed posthumously by his son Wolfgang, focused on the distinction between the style of Jordaens’ and Rubens’ study heads.g

But even nowadays, progress is possible in studying the early Jordaens and is of a particular scholarly interest as many more precise answers for that period can be found through multidisciplinary research. Moreover, this field of research is a domain where the Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project makes a difference through its systematic and comparative study of Jordaens’ panel paintings worldwide and by its interdisciplinary character, delivered by dendrochronology, and by analysing the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke brand marks for quality control (introduced by ordinance in December 1617, in the midst of Jordaens’ youthful career), panel makers’ marks and panel makers’ biographies on the basis of primary archival sources, which are indicative points of reference for putting the quickly evolving production of Jordaens in a more precise chronological order.

Last but not least – and here the circle with Rubens scholar Burchard is complete – the Jordaens van Dyck Panel Paintings Project, by studying Van Dyck and Jordaens in parallel and by doing so through physical examination and multisidisciplinary research, is uncovering more and more indications that both youthful artists established more direct and more intricate connections to the emerging Rubens studio than has previously been considered. Therefore, the story does not end here. It only just begins to venture into new and uncharted waters.

Ludwig Burchard

Current knowledge of the early years of Jacob Jordaens can be best and most succinctly described with the sentence from Thieme’s General Dictionary of Artists, ‘1617 saw the first definitely datable piece from his hand (Crucifixion in St Paul’s church, Antwerp), 1618 the first with a written date (Adoration of the Shepherds in the Museum of Stockholm)’.1 Attempts to confirm other pieces by Jordaens, which could have been produced in 1617 or even earlier, have so far been lacking, if you ignore the failed attempt by Oldenbourg,2 who wanted to attribute Let the little children come to Me (formerly in the Pauwels-Allard Collection) to Jordaens whilst he was still an apprentice to Van Noort (Fig. 1).3

The starting point of the search, which will be described below, is the magnificent and very distinctive representation of the Holy Family (Fig. 2), which was displayed as a new acquisition in the Brussels museum in 1925 and which, when I saw the piece in the summer of 1925, was spontaneously recognisable as a piece by Jordaens, whereby on further reflection, the assumption necessarily took ground, that this had to be an exceptionally early work by Jordaens, surprising as it was in many ways.

A comparison with other pieces by the master proved my first idea to be right. In a short time, a partial match was established with another piece generally recognised to be by Jordaens. And when there was then a second match, the way seemed clear for me to successfully search for other pieces from Jordaens’ early work.

The biographical data do not stand in the way of wanting to prove pieces by Jordaens prior to the year 1618. In 1618, when Jordaens painted the Stockholm Adoration, the artist was already the owner of a piece of land. In the preceding year, on 26 June 1617, he had his first child baptised, after marrying Catharina Van Noort, the daughter of his teacher, on 15 May 1616. And he first decided on the marriage after he, in 1615, at the age of 22, became a free master in the Painters’ Guild in Antwerp. The painter, who was aged 25 in 1618, created the much-admired Adoration of the Shepherds and emerged (probably in 1617) with the even more amazing Crucifixion in the St Paul’s church of Antwerp (Fig. 3) and must have achieved something considerable since he obtained his mastership in 1615, reaching a preliminary high point with the Stockholm Adoration. Even if, for some of the pieces dealt with here, proof has been strictly provided over time that they are by Jordaens and were painted in his early life, even then the series of works presented below may only make up a part of what Jordaens created between 1615 and 1618.

The following overview foregoes presenting the pieces in the suspected order of their creation; it rather begins with pieces that are attributed to the authorship of Jordaens based on comparison, followed by pieces which seem, to me at least, to be no less surely by Jordaens, but of which I currently have no clear evidence.

1. Holy Family with Elizabeth and the infant St. John the Baptist (Fig. 2), full-size, canvas, glued to wood [Editorial note – no longer], 115 x 113 cm, Brussels Museum, No. 965. – According to the Brussels catalogue (second edition, 1927), purchased in 1925 from Max Rothschild, London (The Sackville Gallery).

The piece hung in the Brussels Museum, following its purchase in 1925 with the designation “Flemish School, 17th century”. Not until 1927 did an attribution merge, albeit to Abraham Janssens, and with this name it first appeared in the museum’s 1927 catalogue. In 1926, Édouard Michel had suggested Pieter van Mol as the author of the picture with no certainty regarding this name (Beaux-Arts, 1926, p. 45-46, illustrated). The same author returned to this hypothesis again in his well-informed and instructive book on the Flemish paintings in the Louvre (1927, p.79). Subsequent literature concerning the Brussels painting is unknown to me.

At the beginning of this article it has already been mentioned that the authorship of Jordaens, which was obvious to me the first time I saw the piece, has subsequently been proven as two motifs in this painting recur in other works by Jordaens.

The first match to reveal itself concerns the head of Saint Joseph. This old man’s head, which reminds us of the scenes of Chronos, with the flowing white beard and head hair, has doubtless been carefully studied from a living model in terms of form and lighting.

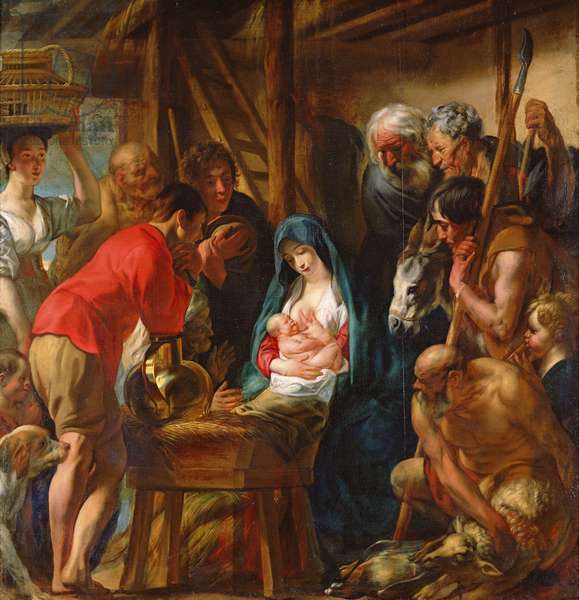

This head of Saint Joseph can be seen quite identically in an Adoration of the Shepherds, with half-figures (Fig. 4), which is conserved in the Brunswick Museum (No. 116. On oak, 125 x 97cm).

The painting in Brunswick is generally recognised to be a piece by Jordaens. This is beyond all doubt when compared with the signed variant in Stockholm (from 1618, Fig. 5).

Evidently, Jordaens used a different head study for the Stockholm variant of Saint Joseph compared with the one used for the Braunschweig variant (and likewise for the repetition by his own hand of the Stockholm painting, formerly with Prince Lichnowsky in Kuchelna, Schlesien [Editorial note: now in the Mauritshuis, Fig. 6]).

For this, Jordaens used the head study, which we have now met twice4 for a third time and again as Saint Joseph at least a decade later, in the Adoration of the Shepherds (with full-length figures) in the Six Collection in Amsterdam [Editorial note: now in the Louvre, Fig. 7].The inference is obvious. After Jordaens presented a Joseph on two generally recognised pieces, which also reappears on the Holy Family under discussion, we have to get accustomed to the idea that Jordaens and no-one else is the painter behind this Brussels Holy Family.

The inference is obvious. After Jordaens presented a Joseph on two generally recognised pieces, which also reappears on the Holy Family under discussion, we have to get accustomed to the idea that Jordaens and no-one else is the painter behind this Brussels Holy Family.

I realised later on that there is another match linking the Brussels paintings with one of the main pieces by Jordaens. However, this match is not easy to recognise at first sight and is therefore even more convincing.

Here is not the place to discuss again the details of this huge altarpiece by a youthful Jordaens The Tribute Money [Editorial note – now titled Christ’s charge to Peter, Fig. 8), a discussion which began decades ago and an attribution to Jordaens has long been decided thanks to Henri Hymans (Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1905, II, 249) and F. M. Haberditzl (Jahrbuch der Wiener Kunstsammlungen XXVII 186f.).5

This canvas, measuring 216 by 243 cm with ten life-size figures, which was donated as a show piece to the Sint-Jacobskerk in Antwerp by the collector Antoine van Camp in 1844, includes a figure crouching on the ground in such an unusual position that it must have been painted by using a detailed study after a life model. A glance at Figures 1 and 3 should be enough for it to be clear how extensively the boy John in the Brussels Holy Family and the crouching figure in Christ’s charge to Peter match!

As to this picture, Max Rooses mentioned a characteristic that is telling for the whole group of paintings discussed here and therefore should be reproduced in so many words, ‘Ten apostles are gathered around Christ on the shoreline. Peter, a venerable old man, completely naked, brings in a fish caught by him. The apostle has warm yellow skin with blue-like dark shadows; a second fisherman is sickly pale also with even darker shadows, a third is bronzed by the sun and wind. The clothing is bright but not quite full of colour. The heads show a strange strength – with the exception of Christ’s head, which is captivatingly beautiful; the apostles are working men, rough, healthy, but without anything ignoble. The lighting effect is important: the sun breaks through the heavily overcast sky, the full glow covers the scene, warming and illuminating, without letting anything shine. The shadows are thrown in broad masses, with the whole painting and arrangement being as broad. All the characteristics of a strong hand adding bold and mild colours and light are combined here’.6

Let us return to the Brussels Holy Family, where we also find the contrasting of “sun-bronzed” and “sickly pale” figures. The dark red-brown of both older people, Joseph and Elisabeth, explains itself. However, the contrast between Mary and Jesus on the one hand and John on the other is noteworthy. While the boy Jesus exhibits the same cold white flesh tones, which is also how Mary is represented, the young John, although intended to be roughly the same age as Jesus, is depicted with dark tanned skin, with this being particularly noticeable as both are entwined in the same group. Later, Jordaens, although not to such a significant degree, distinguished, using different skin colours, between men and women and between noble and less noble figures and thus sought to offer colouristic variety. However, here and in the whole group of paintings, with which we are concerned, this art, which originated from the Mannerism of the late 16th century (such as Spranger and Bloemaert), is pushed to the extreme to such an extent that only the acceptance of a very early origin of this Holy Family can explain a sympathising with the formulae of the dying Mannerism.

Still fully in line with the recognition of Mannerism, is the wavy meandering of light and shadows which also cover the bodies in their entirety. Cast shadows, which can be found on the neck of the boy Jesus and on the right arm of John, announce from afar the “Carravaggism” which reaches a high point for Jordaens in 1618 in the abrupt chiaroscuro of the Stockholm Adoration.

The Brussels Holy Family radiates a brightness and colourfulness that Jordaens never subsequently aspired to. Mary’s hair is as straw-blond as the overturned bird cage and competes with the silky white hair of the elderly Joseph, with the pearly white flesh tones of Mary and Jesus and with the bleached linen of the children’s clothing. The brown-grey stone pedestal is heightened with white highlights with the fur of the light grey cats reflected in the light. The blue-grey sky is overplayed with white. The sap green sleeves of Elizabeth are also heightened with white with Mary’s red dress being broken to a silky white.

And along with the brightness of the images, there is also the colourfulness of the local colours. Next to the red of Mary’s dress is the blue of her coat and the heliotrope of her coat lining (a piece of the overturned coat in question appears to the left of the stone base). Golden yellow lights up Joseph’s coat and the flickering Glory of Jesus. And all this colourfulness seems to be summarised again in Mary’s plate-like head covering, a disc wrapped in stripes in blue, bluish pink, golden yellow and lemon-white (this headdress again evokes memories of a Bloemaert).

The objects only take up a small amount of space and are entirely in the shadows, such as the vine branches which wind around a ladder-like construction and are depicted in brownish sap green.

One more tangible feature should be highlighted. While Rubens, by whom this Holy Family may have been inspired, at the same time distinguished between and opposes cold blue and warm red for the structure of the flesh tones, the bright bodies in the Brussels picture consistently present a mixture, which gives a dazzling purple-grey, which both in its result and principle of colour-mixture is leaning unmistakably towards the colouristic conceptions of late Mannerism. Purple and heliotrope, the colours typically preferred by the last Mannerists, therefore also recur many times in the local colours in the painting, as grey purple in Elizabeth’s cape, as heliotrope in Mary’s coat and as pure lilac in the stripes of the champagne-coloured cloth covering the head and shoulders of Elizabeth.

It follows from the above that I would like to believe that the Brussels Holy Family is definitely a piece by Jacob Jordaens and is one of his earliest pieces.

2. The Good Samaritan. On canvas, 185 by 171 cm, in the possession of Prince Sanguszko in Podorze (Galicia) [Editorial note: now in the Louvre, Abu Dhabi, Fig. 9]. In 1899 it was shown at the Van Dyck exhibition in Antwerp and was unchallenged as a piece by the young Van Dyck until Rudolf Oldenbourg removed the piece from Van Dyck’s catalogue and tentatively proposed that it be attributed to Jordaens.7 I believe, without seeing the painting with my own eyes, that Oldenbourg was quite right and that the painter of this apparently highly-characterful piece should indeed be attributed to Jordaens with certainty. Again, there is a picture that is definitely by Jordaens which can be compared with this and the attribution to Jordaens can be substantiated with a partial match.

In the Warsaw Museum, there is life-size Holy Kinship with Angels (on canvas, 109 by 223cm, [Editorial note, now titled Holy Family with St John, his Parents and Angels, the painting is on panel, Fig. 10), on which the artist must have placed special value since he has signed it in a very detailed way.8 On the stick on which the holy Joseph leans, it reads: I. JORDAENS INVENTOR ET DEPINGEBAT. Also, I would like to believe that this picture was created before 1618 despite the significant convergence towards Rubens, which is already unmistakably evident. But what matters here most is that the Samaritan with his head covered with a turban (Fig. 8) is obviously painted from the same model as the bare head of the Zacharias in the Warsaw piece (Fig. 9) with a single difference, that Zacharias is viewed from above and the Samaritan is viewed from below. The powerful view from below suggests, along with other features, that the “Good Samaritan” belongs to Jordaens’ early work, so between 1615 and 1618.

3. The Good Samaritan (Fig. 11). Washed pen drawing, 23.5 x 20cm, in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne (Inv. L. B. 1435). Considered to be a preliminary study to the piece at Prince Sanguszko’s for a long time (e.g. in Lionel Cust, Van Dyck, 1900, p.11) The inscription “A. V. DYCK” is apocryphal. There is nothing in the way of this study claiming that this piece, which still lacks accompanying figures at the sides, was painted by the same hand as the larger piece.

In this way one could add an example of the drawing style of the young Jordaens. Other examples of how Jordaens liked to draw in his early years seem to remain unknown up until now.

4. Holy Family (Fig. 12). On oak, 112 x 94 cm. In the collection of Ralph H. Booth in Detroit, Mich. (previously in the P. Bottenwieser Gallery in Berlin) [Editorial note: now in the Detroit Institute of Arts]. For this piece that is strikingly beautiful in some of its parts, there are no clear partial matches with pieces generally considered to be by Jordaens. However, I believe that the authorship cannot really be questioned, especially when considering the Brussels Holy Family (Fig. 2).

Some colour information may support the evidence from the illustration. The brightness and colourfulness are not quite as vivid as in the Brussels painting. However, here too, the powerful local colours collide directly with each other, e.g. Mary’s garb: the madder-red of her bodice and the green of her coat roughly depict the same tone as the red-green of a fresh fig. There is also a third tone which can be seen on the shoulder of the inside of the coat where it is folded-over, a madder-pink with yellow hues. Mary’s headscarf is blue-grey as is the coat of Saint Anne.

And again, the Mannerist preference for colourful stripes! Aside from the thin red marking of the coral necklace around the neck of the child and the colourful stripes on the headscarf of Saint Anne, one should point to the way the child’s wrap alternates between salmon red and white stripes. The flickering aureole over the heads of Mary and Jesus is similar to the light above the head of the boy Jesus in the Brussels picture. In addition, the refraction of the local colour through the white light recurs, which is particularly noticeable on Mary’s red bodice. Finally, there is the approach to the carnations. Again, only weak attempts have been made in the transition from light to produce blue, red and brown shadows in clearly separated stages. The cold blue tones do not appear everywhere – as with Rubens – just in the right places, in the transition from light to semi-shade, but flicker into the bright light and give the carnations a restless disquiet, instead of a quiet life as with Rubens. Particularly difficult for the artist is modelling in the shadows. Where Rubens contented himself with a free form transparent brown, which draws the gaze of the viewer, to complete the shadowy body parts at will, the young Jordaens torments himself, when depicting the child’s head for example, which is in the shadows, using a combination of cold and warm colours to model it throughout, whereby a murky red-grey exists next to a dirty green-grey. However, this child’s head is not a measure of the skill that Jordaens had in his early years. He seemingly had no study modelled on a living model that he could use in his composition at this point. He tried to create the child’s head from the stock of his artistic imagination and it has not really been successful since at that time his strength was apparently based more on observation than his gift of imagination. So here, I believe it can also be concluded that we are looking at an early piece by Jordaens which is probably closer to 1615 than 1618.

5. Holy Family. Bust. (Fig. 13). On oak, 66 x 48.5 cm. Privately owned in Reval (the piece was submitted to the Kaiser Friedrich Museum for assessment in March 1927) [Editorial note: now in the Kadriorg Art Museum, Tallinn].

The painting most close to it is the Holy Family with St John, his Parents and Angels in Warsaw (Fig. 10). The great brightness of the Reval piece, which sets aside almost all shadows and barely makes use of cast shadows, pleads for an even earlier date than the Warsaw picture. The brightness and colourfulness are really extraordinary. The colourful reflections in Mary’s headscarf are very finely observed. Mary’s face depicts a girlish tenderness and tautness, which is very similar to the corresponding heads by Rubens. The same applies to the head of Saint Joseph as was said of the child’s head in the Detroit piece (Fig. 12): it is apparently painted from memory and thus fails substantially more in the sense of a traditional Mannerism as the heads of Mary and Jesus have clearly been depicted based on a living model.

6. Holy Family. (Fig. 14). Bust. On oak, 62.5 x 49.5cm. Berlin, in the possession of the author (purchased in March 1928, previously at the Dr. Benedict art gallery in Berlin) [Editorial note: current whereabouts unknown. It was sold at Christie’s, London, 18 April 1997, lot 55]. The painting corresponds to the Holy Family in Reval (Fig. 13) largely and in general; in specific details it differs from the Reval variant in virtually every brushstroke. The composition is somewhat larger framed; the apple’s stalk is not depicted over Joseph’s hand. The flickering yellow light over Mary’s head resembles in every detail the nimbuses in the Brussels (Fig. 2) and Warsaw (Fig. 10) paintings. Autograph variants, with only slight differences, should not surprise us in the work of the young Jordaens when considering that there exist three exemplars of the “Adoration of the Shepherds” (in Braunschweig [Fig. 4], Stockholm [Fig. 5] and formerly in Kuchelna [Fig. 6]).

7. Return of the Holy Family from Egypt. Canvas, 73 x 54 cm, sold by auction from the Chillingworth Collection in 1925. This was most correctly attributed to Jordaens in the auction catalogue (under no. 18, illustrated). [Editorial note: now in the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Fig. 15]. The image that we replicate here, or so we hope, affirms the correctness of the attribution and makes a dating from Jordaens’ early life (before 1618) plausible. This is based on the fact that most historical compositions from Jordaens’ early years – thinking of the piece in St. Jacob’s Church in Antwerp (Fig. 1) – place the concept of his painting under the overwhelming influence of Rubens. However, there is no question of a direct borrowing. How similar to Rubens this marvellous painting is, it may be marked by the circumstance that I, years ago, but only on the basis of a hasty acquaintance with photography and strengthened by the judgement of Paul Ganz, who today still attributes this “Return from Egypt” piece to Rubens, mistakenly believed this piece to be by Rubens (in a presentation on “Sketches of the young Rubens”, held on 6 October 1926 at the Berlin Art Historical Society). The date of origin may be well near to 1618.

8. So-called self-portrait. Life-size half-length figure, on canvas. Florence, Uffizi [Editorial note: now titled Portrait of a Young Man, Fig. 16]. In the Florentine collection of painters’ portraits, it has long been considered as a self-portrait of the young Jordaens. Max Rooses, whom one does not like to contradict in such matters, is believed to have denied that it represents Jordaens. However, it is unanimously agreed that the painting is by Jordaens and was painted in his early years. The exact dating of the picture – I would like to suggest it was shortly before 1618 – is complicated by a crust of dirty varnish and even more so due to overpainting, which is obviously not attributable to Jordaens. The listless drooping collar is impossible in his current form. Even from our small illustration, it is clear that the neck was once adorned with impressive ruffles with a bold high arch. One of the alleged copies cited by Rooses which could give some insight on this point and help with the dating is in a museum in Edinburgh but unfortunately, I have not seen it [Editorial note: Fig. 17, after Jacob Jordaens, Portrait of a Man, oil on canvas, 96.7 x 76 cm, National Galleries of Scotland].

Without going into more detail about the individual portraits and group portraits painted by Jordaens in his early years, so much can already be inferred by considering the Florentine portrait, that some biblical half-length figures on a dark background, which were previously, albeit reluctantly, attributed to Rubens, will emerge over time as being early pictures by Jordaens. For example, belonging to those is a half-length figure of the apostle Paul in the Dutch-English art trade and, notably, a three-quarter figure of the half-naked, half-clad in an animal skin, John the Baptist, whose grave and penetrating gaze is very similar to Rubens, but whose hands, aside from anything else, are unmistakably identical to the hands of the Florentine portraits.

9. Christ as a Gardener with the three Marys. Fig. 18. On oak, 106 x 90cm. Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum (purchased in 1928 from the Dr. Schäffer gallery in Berlin; previously in the Dutch-English art trade).

The painting, which also stands out due to its excellent condition, may well surpass all works, in terms of beauty and significance, which we have tried to attribute to Jordaens’ early work. That is why we kept its discussion until the end, so that everything that took place in the discussion of the early work of Jordaens does not need to be repeated as this piece speaks for itself as the best. We confidently hope that one day there will be external support for the attribution to Jordaens.

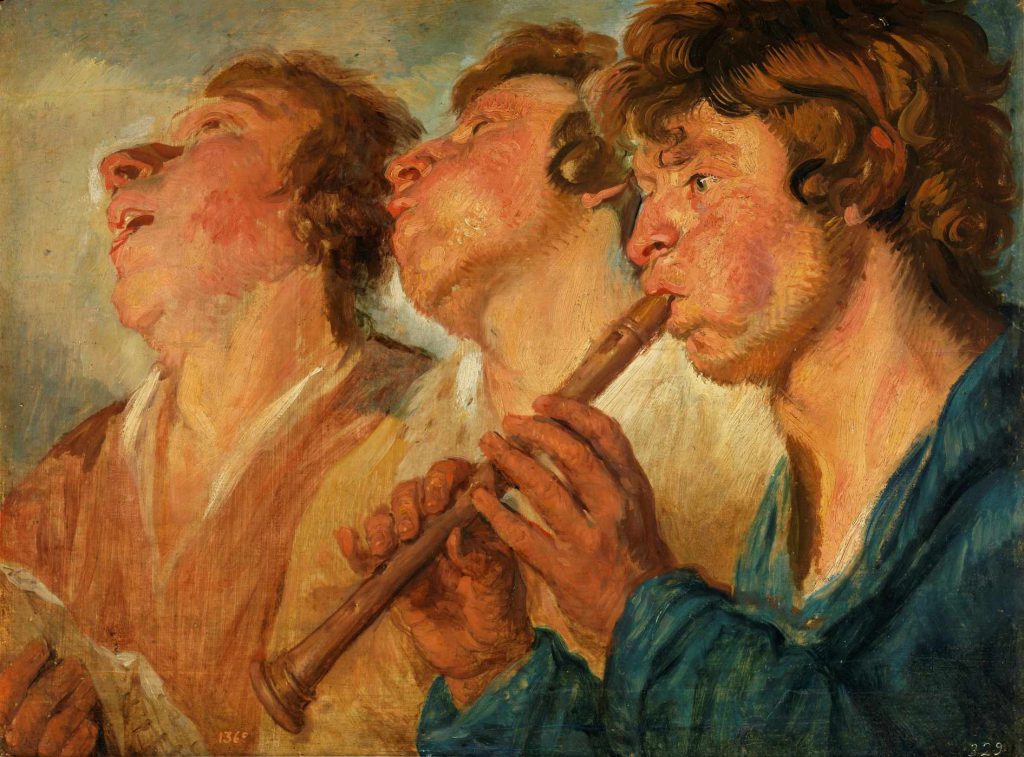

For the heads of the three Marys, studies of living models are assumed to have been used. Presumably, there was a panel painting showing these three heads next to each other. Such study pieces by Jordaens, which were then usually dismembered in later times into their individual parts (corresponding studies by Rubens met the same fate), are still to be found here and there; I refer here only to the picture with “three musicians” in the Prado (Fig. 19), to the one with “two women and a man” in Antwerp (Fig. 20), to the one with “three young women” in Hermannstadt [Editorial note: now in The National Museum of Art of Romania, Bucharest, Fig. 21].

In the picture in Hermannstadt, all three women are apparently based on one and the same female model. It appears that the study that we have to assume for the “Three Marys”, relates to one and the same model in three different poses; because only in this way can it be explained so naturally as to why the three female heads in the Berlin piece are sort of cut off from each other’s face in terms of age, form and expression. The head of Mary looking up in exaltation, seems to add at the very least one analogy to the pictures already recognised as being by Jordaens, as unmistakably reminiscent, in attitude and expression, of the head of the upwards-looking beardless fisherman who is attending on the right side the miracle of Christ’s charge to Peter (Fig. 8) with full faith and confidence.

The colouring and shaping of the mature and late Jordaens are often compared to the mild, chromatic and infinite unbroken colouring of autumn or with the cloudy and somewhat obscured colour of an evening twilight. His early work is bright like a summer’s day, outside, as bright as the noon, in the glistening sun. Then, around 1618, in his Caravaggesque period, he abandoned the ideals of his youth for a short time. As if he had tired of the sun and the dazzling colours, he withdrew to the darkness of a workshop which only allowed streaks of light to penetrate a high window. His works are essentially formless and black with plastic dominating colour, the safety of the drawing dominating the passion of bright colours. The carefree interplay gave way to strict self-discipline for a while. His work then begins to flow freely without the direction ever fundamentally changing again, without the rapid fluctuations of his beginnings but also without the effervescent and wild vigour.

a. R.-A. D’Hulst, Jordaens, Antwerp, 1982 – editions in Dutch (Mercatorfonds, Antwerp), French (Albin Michel, Paris), English (Sotheby’s, London) and German (KlettCotta, Stuttgart).

b. For Ludwig Burchard, see Lieneke Nijkamp, Koen Bulckens, Prisca Valkeneers, (eds.) Picturing Ludwig Burchard, 1886-1960, A Rubens Scholar in Art-Historiograph!cal Perspective, (London / Turnhout, 2015).

c. Paul Buschmann, Jacob Jordaens. Eene studie naar aanleiding van de tentoonstelling zijner werken ingericht te Antwerpen in MCMV (i.e. Jacob Jordaens. A study at the occasion of the exhibition of his works organised in Antwerp in 1905), Brussels, 1905; Max Rooses, Jordaens, Sa vie et ses oeuvres, Amsterdam-Antwerpen, 1906, (also an edition in English: J.M. Dent & C° – E.P. Dutton & C°, London-New York, 1908).).

d. R.-A. D’Hulst, Jacob Jordaens. Schets van een chronologie zijner werken ontstaan vóór 1618 (i.e. Jacob Jordaens. Sketch of a chronology of his works created before 1618), in Gentse Bijdragen tot de Kunstgeschiedenis en de Oudheidkunde, XIV, 1953, pp. 89-138; Idem, Drie vroege schilderijen van Jacob Jordaens (i.e. Three early paintings by Jacob Jordaens), in Idem, XX, 1967, pp. 71-86.

e. In one case, the most recent auction at which it appeared.

f. Exhibited in the Brussels museum at its acquisition in 1925 as Flemish School 17th century; attributed to Abraham Janssen in the Brussels museum’s collection catalogue of 1927, p. 126, nr. 965; as Pieter van Mol in E. Michel, Pieter van Mol et ‘La pêche miraculeuse’ de l’église Saint-Jacques à Anvers, La Revue d’Art, XLV, 1928, pp. 138-139. For a more recent overview of literature on this painting, see the exhibition catalogue Hans Devisscher & Nora De Poorter (eds.), R.-A. D’Hulst, Nora De Poorter & Marc Vandenven, Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), vol. I: Schilderijen en Tapijten / Tableaux et Tapisseries, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp, 1993, cat. nr. A2

g. Ludwig Burchard and Wolfgang Burchard, Jordaens Head-Studies Wrongly Attributed to Rubens, in Bulletin Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique / Bulletin Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, IX, (1960), pp. 175-182.

1. K. Zoege von Manteuffel, Jordaens, Thieme-Becker XIX, 1926, p. 151.

2. Rudolf Oldenbourg, Die Flämische Malerei (Flemish Painting), Berlin 1918, S. 107 – F. M. Haberditzl, the first to dispute “Let the little children come to Me” being attributed to Adam van Noort (Jahrbuch der Wiener Kunstsammlungen XXVII, 1907-09, p. 179 f., Taf. XXX), was, in any case, careful enough not to simply attribute the piece to Jordaens but to situate it only in his direct circle. In the meantime, the issue of the authorship of “Let the little children come to Me” had settled itself. In 1927, Ms. G. Pauwels-Allard’s collection was prepared for auction and, when cleaning the piece, the monogram of Adam van Noort came to light (see Jean Decoen in the auction catalogue, Brussels, Giroux Gallery, 21/22 XI. 1927, under No. 53). The piece was purchased by the Brussels museum at the auction.

3. Another search in this respect, by François Benoit (Revue de l’art ancien et moderne, XXIII, 1908, No. 131, p. 87 ff) has justly never been taken seriously. Benoit has to be given credit to have recognised, simultaneously with Haberditzl, Jordaens’ hand in “Jesus at the house of Mary and Martha” at the Lille museum. However, his efforts to prove the Lille piece to be a very early piece by the artist failed. Haberditzl may have got it right when he (Jahrbuch Wien, loc. cit. p. 185) said of the Lille piece: “its date would be somewhat around 1630”. One should compare with Hans Kauffmann’s recent opinion in Festschrift für Friedländer, 1927, p. 206, note 22.

4. In addition, other head studies from the artist’s early work recur in the same sense in thematically-different pieces. The Mary in the Stockholm Adoration uses, which has already been observed several times, the head of the “Temptation of the Magdalene” (Lille, No. 427), which latter picture should therefore be dated to around 1617. The piece in Lille is still not as markedly Caravaggesque as the Adoration in Stockholm, it is more colourful, less black and white and therefore probably earlier than the Shepherds Adoration from 1618 in Stockholm. A relatively early dating of the piece in Lille was also supported by F. Benoit and P. Buschmann (Jordaens, 1915, p.63).

5. Without reservation, E. Heidrich (Vlämische Malerei, 1913, fig. 124) and R. Oldenbourg (Handbuch, 1918, p.107) are e.g. also in favour of Jordaens.

6. Rooses, Geschichte der Malerschule Antwerpens, translated by Franz Reber, 1889, p.144. The characteristics represented can be considered all the more unbiased as Rooses did not want to believe that Jordaens had a hand in The Tribute Money.

7. R. Oldenbourg, Die Flämische Malerei des XVII. Jahrhunderts, 1918, p.63.

8. W. Tatarkiewicz, Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst 1910, p. 256, fig. 8.