Joost Vander Auwera

This article by Jan Van Damme on panel makers and their marks was first published in Flemish in 1990 in the ‘Jaarboek’ of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp (see this page for the original article in Flemish). It is well deserving a translation into English in order to make it accessible to a wider audience of scholars and art lovers. We are grateful to the author as well as to Prof. Dr. Manfred Sellink, General Director of the Antwerp museum, for their support in giving us permission to publish it a second time in this way, including some addenda and corrigenda.

In fact, although dating from almost thirty years ago, Van Damme’s contribution remains as ground breaking as it was then and the most authoritative article on the subject . Moreover, it illustrates in an exemplary way the effectiveness of that sort of multidisciplinary approach that is also key to the Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project. Indeed, Van Damme has a hands-on approach to the artwork as a material object: he studies it with the eye of a detective, looking for those minute details on the backside of the wooden support that only such material study on the spot can reveal. And he combines this painstaking analysis with a wide-ranged and in-depth study of primary archival sources to which he has direct access as a native speaker.

This publication – just as this evolving website – is continuously in progress with all the potential for further updating that a digital context is offering. In fact, what is translated here is the corpus of the text, containing the general overview of the trade and its historic disputes and regulations, followed by the biographical data on panel makers active in Antwerp and their marks, followed by the annex with the regulation of 11 December 1617.

By returning to the primary sources in the archives, several additions and corrections could be made by the JVDPPPP Archival Fellows Ingrid Moortgat and Piet Bakker whereas the recent renumbering of some public archival sources could also be taken into account. This supplementary evidence has changed the original number of the footnotes. To distinguish these from the original article, they are marked in the text in bold.

They have also conducted further research into the panel makers whose marks JVDPPP have discovered on the back of panel paintings by Van Dyck and Jordaens: Guilliam Aertssen, Michiel Vriendt, Guilliam Gabron, Sanctus Gabron (a mark first identified by Drs. Justin Davies in December 2016) and Michiel Claessens. Their biographical timelines can be found here. They contain important new information and provide further evidence of the close-knit nature of Antwerp’s artistic milieu.

Since 1990, the ownership of many panels containing marks which Van Damme listed under each individual panel maker has changed. Therefore, at this stage, it was not workable to update systematically their current localisation. We therefore prefer to refer to the original article instead of translating this data. And this is also the case for the images from the 1990s of artworks whose current whereabouts are unknown. On the other hand, the rapid evolution of photographic technology during the last 30 years and our research travels to see Jordaens and Van Dyck panels in real, have permitted us to replace in some instances the older and less precise documenting of panel makers marks through rubbing, with more detailed and clearer digital images. Those images are inserted alongside the name of the individual panel maker.

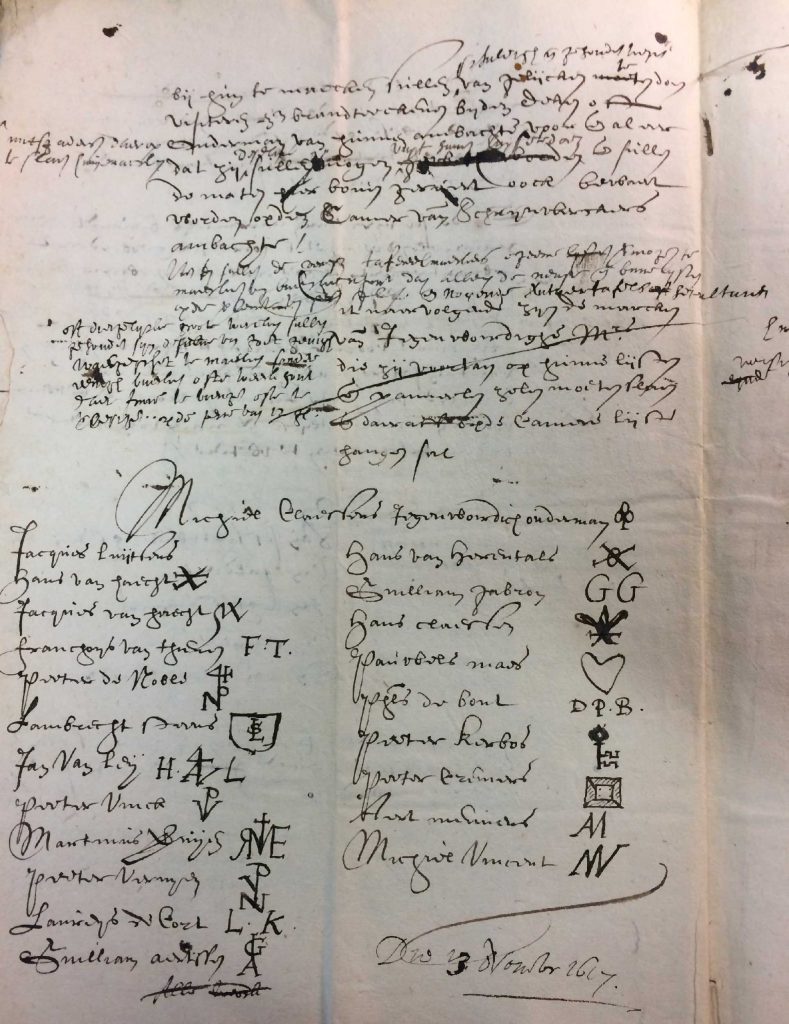

We also publish the first time in any language the full text of the panel maker’s petition of 13 November 1617 which was referred to in footnote 8 by Jan Van Damme. We publish photos of the original documents, its transcription and translation into English next to it. This procedure will permit the scholar to return always to the original source and hopefully also to appreciate the painstaking work that has been done to stay as close as possible in this translation to the intricate meaning of each term, be it general or technical in nature, and both in the modern and the 17th century Flemish language.

Masters

Unidentified masters

How to cite: Van Damme, Jan. “The Antwerp panel-makers and their marks.” In Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project. Updated by Ingrid Moortgat and Piet Bakker, edited by Joost Vander Auwera, with an introduction, and Justin Davies. Translated by Michael Lomax.

http://jordaensvandyck.org/article/the-antwerp-panel-makers-and-their-marks/ (accessed 10 March 2026)

J. Van Damme

‘Audio etiam, Antwerpiae, & alibi, ubi fracta per sectarios Altaria, iterum, Deô nobis propitiô, erecta sunt, rariores in Alteribus poni Statuseas Sanctorum: crebriores verò depictas Tabulas; idque non aliam ob causam, quàm plus artificii dicatur esse in illis Picturis, quàm in Statuis’ 1, wrote Johannes Molanus2 in 1594, pointing correctly to an unmistakeable evolution which, although starting earlier, fundamentally changed the appearance of many church interiors in the wake of the iconoclast storm. The St. Anna Altarpiece (1509) and the Pieta (1508-1511) by Quinten Metsijs suffice as illustrious examples. Exemplary is the redecoration of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw church in Antwerp following the fire which ravaged it is 1533, including the Fall of the Angels by Frans Floris (1554)3. Even before the iconoclast storm of 1566, the once so important production of carved altarpieces in Antwerp had passed its peak.

That the shift to painted altarpieces did not benefit the woodcarvers is obvious, but their suppliers, including the bakmakers, literally ‘basin-makers’ or ‘tray-makers’, who produced the frames or ‘hutches’ for the carved depictions, were also quick to suffer the effects. From around 1500 the bakmakers had offered their services, as specialist craftsmen, to woodcarvers not wishing or unable to produce themselves the hutches in which their groups of figures were set up. With the expiry of demand for carved altarpieces a new field of work lay open. Painters continued to call on the bakmakers for supplying them with wooden panels, or in the terminology of the time ‘taferelen’ (tableaux), and frames. Prior to that, the bakmakers had already delivered panels and frames for the painted wings of carved altarpieces. That we are talking about the same professionals is clearly visible from the records of the Antwerp Guild of St Luke. Bastiaen van Hove was registered in 1543 as master bakmaker but is mentioned two years later as a tableau-maker. Peeter van Haecht and Franchois Staefmaker were registered in 1543 and 1545 respectively as master bakmakers and mentioned in 1554 and 1551 as tableau-makers. Geert Jansen did his apprenticeship in 1551 with a bakmaker and was received into the guild ten years later as a tableau-maker (tafereelmaker).4

The activity of the tableau-maker, often called also a panel-maker (paneelmaker) and later frame-maker (lijstmaker)5, was obviously not limited to the preparing of panels and frames for large altarpieces. The increasing success of genre painting provided an additional market for their products. It is precisely in this genre painting and its increasing success, thanks to the blossoming art trade, that the future of the Antwerp tableau-makers lay. At the start of the seventeenth century art production in Antwerp had reached such proportions that no less than some twenty tableau-makers’ workshops were able to ply their trade there.

It is perhaps the increasing number of and the ever growing demand for panels that gave rise to a perceived need for a better organization of the profession. The fifteenth-century regulations on quality control and the marking of the altarpiece hutches with the castle and hands from the Antwerp city coat of arms had been taken over with little ado6, but this was apparently felt to be insufficient. Additionally, for tableau-makers, neither the apprenticeship period or the ‘masterpiece’ requirements for gaining master status had so far been established. To provide this, the Antwerp tableau-makers petitioned on 13 November 1617 the magistrates to regulate their profession by means of an ordinance.7 As a consequence of this, on 11 December of the same year a regulation was issued that follows to the letter the proposals set out in their craft’s petition (rekwest).8

One of the most important articles in the new ordinance required each master, from then on, to mark his panels and frames with a personal mark; comparable with the master mark of a silversmith or tinsmith, before having them approved by the craft and ‘whitened’ (i.e. gessoed). Twenty-one tableau-makers placed on the petition of 13 November 1617 the mark that they proposed using from then on (fig. 1). That this list considerably simplifies the identification of the masters whose marks are found on panels is self-evident. But neither does it resolve all identification problems. Not only have a number of marks on the list until now not been found on any panels, but vice versa a number of marks do not appear in the list or do so only in variants. The 1617 list is therefore incomplete, and this and for various reasons. First of all it mentions only masters from the Guild of St Luke, whereas the Antwerp joiners (schrijnwerkers) were also permitted to produce panels.9 The origin of this right of the joiners to deliver panels is already included in an ordinance of 1477. This stated that woodcarvers who were unable or unwilling to produce themselves the hutches for their altarpieces had to use free masters from the joiners’ craft.10 In their statute (keure) of 1497 the joiners had this agreement confirmed explicitly once again11 and in 1510 the craft took woodcarver Geerde Teerlinck to court from not adhering to it.12 When then in 1617 the tableau-makers presented their petition, the joiners’ craft reacted promptly with the request to grant them also a regulation in this respect.13 As a result the city magistrates granted them on 11 December 1617 an ordinance identical to that of the tableau-makers within the Guild of St Luke14 (annexe).

It appears unlikely, however, that before that the joiners also frequently supplied altarpiece panels. We do have the example of Cornelis Boom, who in 1567 restored the panel and frame of the altar of the Guild of the Young Crossbow in Antwerp’s Onze-Lieve-Vrouw church.15 When, however, in 1568 joiner Matheussen Halbeeck received the commission for a new altar of St Martin in the same church, the panel was outsourced to tableau-maker Gheeraerde de Vreese (or Vriese)16 , who in the same year also supplied the panel for the Adoration of the Shepherds by Frans Floris in the gardeners’ altar. The altar itself was from the hand of joiner Antoni Boshof.17 Daniël Arents, who in 1585-87 delivered parts for the haberdashers’ altar and produced the panel for it18, was known as a joiner but was also a member of the St Luke’s Guild as a frame-maker.19 Sebastiaen ‘de scrynwercker’ (joiner), who in 1586 produced the woodwork and the panel of the schoolmasters’ and soap-boilers’ altar in the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw church20, is perhaps identical with joiner Sebastiaen van Halen who doubled as a tableau-maker.21

Otmaar van Ommen, who in 1587 supplied a panel for the cannoners’ altar and the hutch with doors and panel for the St Antony’s altar, also in 1593-94 enlarged the panel of the St Ivo’s chapel in the Sint-Jakobskerk and narrowed the altar table of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-Lofkapel in the present cathedral. In 1604 he delivered an altar table for the high altar in the church of Temse and in 1609 another for that of Nieuwkerken. The panel for the memorial to Jan Moretus and Martina Plantin (1611-12) in Antwerp cathedral also comes from his workshop. Van Ommen, who was to make his name as a joiner, was however also registered with the St Luke’s Guild as a wood and antique ornament carver.22 The well-known chronicler Godevaert van Haecht and his son Peter were both joiners and tableau-makers.23 Hans van Beemen, alias van Herentals, was a master in both trades24 and Michiel and Franchois Gast too were both joiners and members of the St Luke’s Guild.25 The above list serves only to demonstrate that the joiner in practice was not a tableau-maker. If in practice joiners had also been tableau-makers, not so many would have felt the need to acquire a masters’ status also in the St Luke’s Guild, with all the associated costs. Also striking is the extreme rarity of mentions of panels or painting frames in the estate inventories of joiners.26 Additionally, in 1621, in a dispute between the ebony-workers’ corporation (natie) and the St Luke’s Guild, the Antwerp magistrates’ bench expressly ordered that the former should become masters in the joiners’ craft unless they produced solely ebony frames. In that case they would fall under the guild27, a decision that would have been pretty illogical if the joiners had produced frames for paintings as well. The accounts of the joiners’ craft for 1608-09 do not mention tableau-makers either28, and there is also the testimony of tableau-maker Guilliam Gabron who in 1662, then aged seventy-five, declared that he knew no single example of a colleague who had learned his trade among the joiners.29

Despite all this, one should not automatically assume that marks not appearing in the 1617 list belonged to tableau-makers who only later joined the group of masters in the St Luke’s Guild. The records mention more masters before or in 1617 than appear in the list. Missing in the latter are the names of Peeter de Backere, Hans Goossens, Thomas van Oudendyck, Peter Sevens and Peter van Hellegaert (or Hullegaerde).30 The name of Jacques Luytsens appears on the list but his mark is missing.

In the past the marks of another kind were frequently incorrectly interpreted as those of tableau-makers. Most of these involve the so-called plant-like motif that on closer inspection turns out to be a badly struck or partly shaved away fortress mark (fig. 2). Nor should a strange variant of the fortress mark (fig. 3) be viewed incorrectly as a panel-makers’ mark. In other cases it is a letter A (fig. 4).31 Seeing, however, that this mark frequently occurs together with the fortress mark and a panel-maker’s mark, another significance needs to be attached to it. This meaning is unclear. At least one example is known of a branded letter B (fig. 5), which can suggest that these are year letters. However, a regulation on this subject is unknown.

Other interpretation problems arise from the fact that a number of marks on the 1617 list have been found on panels solely in variant forms. For example Lambrecht I Steens gave his intertwined initials in a little shield as his mark. The panels known to us until now show the initials without the little shield (figs. 1 and 6). Franchois van Thienen gave in 1617 the initials FT, while until now only panels with FVT are known. Guilliam Gabron recorded the initials GG. Panels show only the variant G+G (figs 1 and 7). A possible explanation for these deviations is to be found in the distance in time between the rekwest and the execution of the ordinance. Their occurrence pleads in favour of the opinion that the marks on the 1617 list were not previously in use. Another fact pointing in the same direction is that none of the marked panels known to us can manifestly be dated earlier.32 Apart from the mark itself, it appeared that the method of marking was not established from the outset. The ordinance itself did not give the least indication, and while most marks were carved out with a gouge or struck with a cold marking-iron, at least one master initially placed his mark in red chalk (fig. 8). After that he used a gouge and cut his mark in at least two different ways (figs. 9 and 10).

From the above it would appear that 11 December 1617, or indeed probably 13 November of that year, can serve as a terminus post quem for paintings carrying a personal tableau-maker’s mark. In a number of cases and on condition that no son or widow took over the master’s workshop along with his mark33, the date of death of the master in question also gives an approximate terminus ante quem, approximate because an undefined period of time that could pass between the manufacture and marking of a panel and the painting of the same. One can assume that most panels were painted almost immediately. Lucas Floquet, a free painter but above all paintings merchant, and art dealer Gaspar Antheunis both went as far (1628) as to employ a master tableau-maker permanently because, as Floquet maintained, the tableau-makers were unable to deliver his orders fast enough34, let alone have major stocks available.

The ensuing dispute with the tableau-maker’s natie is also important for the interpretation of the tableau-makers’ marks by the light it sheds on the role and organization of the art trade. It illustrates the role of the art dealer as an organizer of art production. Visibly the tableau-maker did not always deliver directly to the painters but often also to merchants who first took the panels to the whitener to have them gessoed35 and only then made them available to the artist. Other sources confirm this. In this way in 1614 merchants Lucas Floquet, Guillaume Wittenbrood and Hans Goyvaerts still owed Michiel Claessens money for panels he had delivered. In 1638 it was Michiel vander Haghen and again Guillaume Wittenbrood.36 It should be pointed out that tableau-makers also at times operated as paintings merchants. Hans van Haecht entitled himself, inter alia, as ‘marchant de painctures’ already in 1616, that is before the master’s marks were introduced.37 It is perhaps in such circumstances that an explanation can be found for the fact that his mark has until now not been found on panels. Also the marks of Jacques van Haecht, Peeter de Noble, Jan van Leij(den), Peeter Vinck, Martinus and Peeter Vernyen, Hans Claessens, Pauwels Maes, Peeter Kerbos, Peeter Cremers and Aert Mennens have not until now been found. However, other explanations are also possible. One needs to bear in mind that several tableau-makers who placed their marks on the 1617 list died already shortly after and also that until now only a very limited number of paintings have been examined for the presence of marks. In addition, a large number of marks have gone lost in the processes of restoration, cradling or transfer onto canvas.

From the above it is clear that, for a further study of tableau-makers’ marks, the biographies of the various masters are essential. The biographies that follow are in most cases only the first rudiments of such.

Michiel and Hans Claessens

Michiel Claessens, the brother of artist Artus Claessens, worked from 1590 to 1637, dying on 5 September that year.38 A Michiel Claes, frame-maker, was in 1615 mentioned in the guild records as a master’s son. In all probability this was a scribal error and it was Michiel’s son Hans who became master.39 Hans died in 1622-23.40 His mark is not known.

Marked panels 41 (see list in original Dutch text)

Jacques Luytsens

Jacques Luytsens, whose name clearly appears on the 1617 list of marks, did not record a mark. This may be because, having become a master already in 1573, he was himself no longer active. His death duty is recorded as having been paid in the accounts of the 1619-20 accounting year.42

Hans and Jacques Van Haecht

Hans (1557-1621) and Jacques (? – 1638) Van Haecht came from a well-known family of painters, tableau-makers, joiners and art dealers. Hans was the son of joiner, tableau-maker and art dealer Peeter van Haecht and the brother of Godevaert II, tableau-maker, art dealer and chronicler.43 Although known primarily as an art dealer, his accounts remain, according to which he delivered panels. He also worked on the haberdashers’ altar in the Antwerp Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk (1603) and on the high altar in the St. Jakobskerk (1605).44 He made several deliveries to P.P. Rubens.45 Despite this his marks have until now not been found.

The same applies to his nephew Jacques Van Haecht, the son of tableau-maker Jan Van Haecht. He died in 1638, but already in around 1624 moved to Amsterdam.46 Of him it is known that prior to this he in effect delivered panels.47

Franchoys van Thienen

Details on Franchoys van Thienen are particularly scarce. Apart from the fact that he became a master in 1602 and in 1610 took on an apprentice48, all that is known of him is that in 1616-17 he lived in the Everdijstraat.49 The mark that he gave in 1617 (FT) is known until now only in the variant FvT.

Marked panels (see original Dutch text)

Peeter de Noble

Peeter de Noble became a master in 1604 and thereafter trained at least six apprentices in the profession.50 On 19 November 1618 he still called himself expressly a tableau-maker and but later mostly joiner, as when selling a hereditary annuity (erfrente) in 161951 and on delivering a carved frame for the high altar in the church of Edegem or on the occasion of a restoration of the St. Antonius altar in the same church, in 1617-18 and 1631-32 respectively.52

Lambrecht I and II and Jaspar Steens

The mark that Lambrecht I Steens recorded in 1617, albeit with the omission of the little shield around the initials, is one of those that occurs regularly (figs. 1 and 6). That fact that this is a variant is no reason to assume that what we have here is the mark of Lambrecht II, master in 1640-41.53 It occurs regularly on panels that are clearly older, including of two oil sketches by P.P. Rubens from 1620.54

Lambrecht II died in 1650-51, the year in which Jaspar became a master.55 The latter may have used the initials G(aspar) S as a mark.56

Marked panels (see original Dutch text)

Jan van Leij(den)

Jan van Leij is perhaps to be identified with Jan van Leyden, apprenticed as a ‘laeymaker van spiegellen’ (mirror frame marker) in 1579, and who became a master under the name of Hans van Leyen in 1588.57 The 1617 list gives the first name Jan, but the mark contains the initial H(ans) and L(eyden).

Peeter I Vinck acquired his master’s status in 1609 as a whitewood frame maker, i.e. he specialized in making frames in whitewood and not in oak, which is perhaps the reason why his mark in not found on panels. He died in 1617-18.58

Peeter II Vinck also specialized in frame-making. He was registered as a new master ebony frame-maker in 1626-27.59

Peter and Martinus Vernyen

The figure of Peter Vernyen is little documented. As ‘gelaesscryver’ (writer on glass) of this name became a master in 1568 as a master’s son.60 Possibly it was his son who is mentioned in 1616 as living on the Lombardenvest and as a ‘lijstmaker int weeck’ (softwood frame-maker) by profession.61 The same Peter Vernyen ‘softwood frame-maker’ was involved in the purchase of a house in 1625.62 The fact that he specialized in delivering frames in cheap softwood perhaps explains why his mark has to date not been found. Examples of Martinus Vernyen’s mark are equally unknown. In the records of the St. Luke’s Guild he is mentioned as a ‘decorator’ (stoffeerder) (1612) or softwood frame maker’ (1617-17).63

Laureys de Cort

A Laureys de Cort became a master in the St. Luke’s Guild in 1609. The records do not mention on this occasion any profession.64 In the administrative records maintained by Jan Moretus as dean of the guild (1616-17) he is mentioned, however, as a frame-maker65, just as in the inventory on decease of Antwerp artist F. I. de Leen (1612).66 On purchasing a house in 1611 he refers to himself nonetheless as a tableau-maker.67 His initials L.K. have not so far been found on panels.68

For a biographical timeline on Guilliam Aertssen, click here.

Guilliam Aertsen was accepted into the guild as a master frame-maker and tableau-maker in 1612.69 In 1624 he appears again as the assessor of all wood and tools in the workshop of Michiel Claessens.70 Three years later he was permanently employed by painter and art dealer Gaspar Antheunis.71 In 1638 he was possibly still alive.72

The mark that Guilliam Aertssen recorded in 1617 does not appear on panels. But a considerable number of panels carry a mark that, despite the fact that is deviates considerably, can be viewed as a variant (figs. 1 and 9). Inter alia it appears various times on frames and panels from the ensemble in the winter room of Rosenborg castle in Copenhagen, an ensemble that was assembled, at least in part, in the first years following the issuance of the regulation on marks.73 On one occasion it occurs in combination with the mark of Hans Van Herentals († 1624)74 and none of the other initials of the tableau-makers who acquired master status between 1617 and 1624 can with any evidence be associated with the mark in question.

Marked panels (see list in Dutch text)

Hans van Herentals

The identification of Hans van Herentals is not unproblematic. In 1596 an apprentice tableau-maker of this name was registered in the workshop of Hans Van Haecht. He obtained master status in 1598 and as such took an apprentice in 1619-20.75 In 1597 the joiner’s craft took Hans van Herentals to court, accusing him, as an unfree joiner’s servant of undertaking joinery for the account of the same Hans Van Haecht.76 This tells us with near certainty that this tableau-maker is identical with the joiner Hans van Beeman alias van Herentals who on 20 December 1607 together with his wife appeared before an Antwerp notary.77 Hans van Beeman possibly came from Herentals. In any event he had family living there.78 On 4 December 1618 his last will and testament was enacted in Antwerp and as profession he gave there indeed that of tableau-maker.79 Hans van Beem(en), tableau-maker, died on 1 September 1624 in his house in the Sleutelstraat.80 He is not to be confused with joiner Hans Hoevers (Soeners, Soeniers, Hoeners, Houvers etc.) who in 1596 proved, with certification from the aldermen of Herentals, that he had done his apprentice years as a joiner there and did not need to repeat them in Antwerp.81 He too used the alias Van Herentals.82 Hans Hoevers alias Van Herentals died at the end of February 1626.83

Hans Hoevers and Hans van Beeman must have known each other well. The accounts of the joiners’ craft for 1608-09 mention both of them with a workshop with eight servants and one apprentice.84 During the 1615-16 year of office they were both together dean of the craft85, and at Hans van Beeman’s death Hans Hoevers appears to have still owed him money.86

Marked panels (see list in Dutch text)

For a biographical timeline on Guilliam Gabron, click here.

Guilliam was the son of Jan Gabron, old clothes buyer and paintings merchant.87 From his marriage with Magdalena Cossiers nine children were born, among them painters Guilliam and Antoon. Their daughter Anna-Maria married the well-known carver Artus Quellin.88 Guilliam Gabron acquired his master’s status as a tableau-maker in 1609. In 1616-17 and 1619-20 he was still training apprentices.89 Of his activity as a tableau-maker all that is known from the archives is that painter Daniel Christiaenssen at his death in 1621 still owed him five guilders and seventeen stuivers for panels delivered.90 Guilliam Gabron’s mark, a variant of the one that he recorded on the list (figs. 1 and 7), is often encountered on panels. This frequency can be due both to the importance of Gabron’s workshop and to the fact that remained active for an exceptionally long time. As late as 1662, then aged over seventy-five, he testified to the training of a tableau-maker.91

Marked panels (see list in Dutch text)

Pauwels Maes

All that is known of Pauwels Maes is that he acquired his master’s status in 1614 and that the death duty for his wife was paid in 1616 or 1617.92

Philips (Filips), Melchior and Franchois De Bout (De Bont, De Baut or Debbout)

‘Flips Debout, the whitener and frame-maker’ was accepted in 1604 as a ‘wine master’93 into the St Luke’s Guild.94 He died in 1625, leaving two sons: Melchior, 21 years old and Franchois I, then about 14. A third son Jeronimus died after his parents but before the estate inventory could be drawn up.95 Philips’ workshop was clearly taken over by Melchior. To this end the latter became a master as a ‘whitener and frame-maker’ in 1625-2696 and in 1627 purchased Franchois’ half of the parental house, the Cromhoudt in the St.-Anthonisstraat.97 Given that Melchior acquired his master’s status only in 1625/26, his mark obviously does not appear in the 1617 list. Until now it has not been possible to identify him in any other way. It is true that a panel attributed to Sebastiaen Stoskopff, who after 1619 must have lived, inter alia, in the Netherlands, carries a mark consisting of the interlinked letters M and B (in mirror image). Melchior died around June 1658, leaving three children: Franchois II, Elisabeth and Nicolaes.98 In the same year the Cromhoudt was sold to tableau-maker Peter Coen.99 Franchois II had already acquired his master’s status a few years earlier, in 1655-56, as a frame-maker in the St. Luke’s Guild.100 The mark of Philips De Bout, as shown in the 1617 list (D P.B.) is found nowhere. But the mark DFB occurs repeatedly, including on a work of A. Adriaenssen (1587-1661) dated 1647, i.e. before Franchois the younger became a master.101 Perhaps this was therefore the mark of Franchois I De Bout.102

Panels marked ‘MB’ (see list in Dutch text)

Peter II Kerbos

Peter II Kerbos, frame-maker and son of Peter I, mirror case maker and tabernacle-maker, was accepted as a master into the St. Luke’s Guild in 1608. He died shortly after October 1626.103

Peter I and II Cremers

Peter I Cremers acquired his master’s status as a (mirror)case-maker in 1596.104 The mark in the list has to be his, as tableau-maker Peter II Cremers became a master only in 1625-26.105

Aert Mennens

Aert Mennens learned his trade from Peter de Noble (1605) and himself acquired master’s status in 1614.106 He died in 1620.107 As a profession that of frame-maker is always given.

Michiel Vrient

In 1605 Michiel Vrient was registered as an apprentice in the workshop of tableau-maker Robijn Pulinck. Ten years later he acquired his master’s status, after which he taught the trade to several apprentices.108 The fact that Michiel Vriendt ran a successful workshop can be read not only from the relative wealth that appears in his estate inventory, drawn up in 1637.109 Numerous accounts and other archival data110 show this, as does the frequency with which his mark is found. After the master’s death his widow continued the workshop for about a year, together with Michiel’s brother Nicolaes. In 1638, however, the enterprise was liquidated.111

Marked panels (see list in Dutch text)

Nicolaes Vrient

Following Michiel Vrient’s death on 10 August 1637 and the liquidation of his workshop in 1638, his brother Nicolaes set up his own workshop, for which he himself acquired master’s status as a tableau-maker.112 Among other things he delivered frames mentioned in the inventory of decease of painter and art dealer Jan Snellinck (1639)113 and also glued a panel for the chapel of the Antwerp Wine Taverners (1671-72).114 For the Venerabel Chapel in the St. Jacobskerk he glued a panel (1672-73).115 Only in 1676-77 did the St. Luke’s Guild note his death duty.116 On many panels one finds a mark that looks very similar to that of Michiel Vrient, but consisting of the letters N and V, the initials of his brother Nicolaes. None of these paintings appears to be dated outside the period in which Nicolaes was working.

Marked panels (see list in Dutch text)

Ambrosius Engelants

Panels sometimes exhibit the interlaced initials A and E (fig. 13), a mark that does not appear in the December 1617 list. The records of the Antwerp St. Luke’s Guild point to two tableau-makers whose names correspond to these initials: Ambrosius Engelants (or Ingelant) and Adriaen van Eyckeloy. Van Eyckeloy started an apprenticeship with Lambrecht Steens in 1617-18117, but apparently never got as far as master. Ambrosius Engelants, on the other hand, acquired master’s status in 1625.118 A few years later he worked in the permanent employ of painter and paintings merchant Lucas Floquet.119

Unidentified masters

One frequently encounters on panels six-pointed stars, cut with a gouge, the initials BND, VHB, and FH with a mark, consisting of three interwoven little circles or a little circle with inside it a little cross with wavy arms. The authors of these marks have until now not been identified.

MASTER WITH THE STAR (see here, and for other unidentified masters, the lists in the Dutch text)

MASTER WITH LITTLE CROSS IN A CIRCLE

Regulation governing the making and marking of frames and panels for the joiners’ [schrijnwerkers] trade. 11 December 1617

Copy

We, Hendrick van Varick, knight, viscount of Brussels, Lord of Bouwel, Olmen etc. bailiff of Antwerp and Marquess in the land of of Rijen, burgomasters, aldermen and council of the same city, declare and make known to all persons who shall see these letters or hear them read that as the deans, elders and ordinary keepers of the joiners’ trade of this city had notified us by a request that since time immemorial they have been permitted to make frames, panels, altars, sepulchres, mirror frames120 and similar works, although they have never been subordinate to the Guild of St Luke, and howbeit that it has also come to their notice that that the persons of the same guild, with them the elder of the panelmakers [tafereelmakers] had petitioned us that henceforth nobody should be permitted to let whiten panels and the like and take them out of his house which had not first and foremost been inspected and branded by the elder of their trade, along with other various points whereby their suppliants thought that there was a desire to make them subject to those of the guild of the a Saint Luke, with disturbance and ban on making panels and frames as previously, and petitioned us to be kept and maintained in their old possession and similarly that be enjoined on them by particular ordinance what had been ordained to the advantage and to the service of the trade of panelmakers, and also in order to obtain better and more steadfast work, being prepared to respect the same in a precise manner. Which petition we had placed in the hands of the commissaries with [literally: having received b ] instructions to draft and make the ordinance, which today is also issued by ourselves with regard to the panelmakers. The report having been heard and everything duly deliberated by the council, we have ordained and approved, as we ordain and approve by the present document that the following points concerning the making of frames and panels be maintained precisely by them on the pains set out below:

1. First of all that no joiners may allow any glued panels, large or small, to leave their houses, without the same being first and foremost inspected and branded by the dean of the same trade so that one may be sure that said panels do not contain sap wood or mould, or white or red worms, and this on pain of twelve guilders for every panel.

2. Idem if it happens that in visiting said panels the dean finds any containing sap wood or mould, white or red worms, the owner of said panels must without contradiction permit that these be broken immediately by said dean.

3. And should he find any panels that are not dry wood, these may not be branded by the same person.

4. Idem, from now on, every joiner shall be c obliged to place his mark on frames and panels made by him, on pain of three guilders.

5. And should one again find any panels whitened which have not been properly assessed, branded and signed, the same shall be confiscated, and should the dean find out the person who has had these whitened without previous visit, said person shall be fined twelve guilders mentioned above and the person whitening them also twelve guilders, whatever his quality, man or woman.

6. However, one understands that nobody shall be able to make any works of any kind involving panelmakers before first taking the major examination of the joiners’ trade and having passed free master, and not those who have only purchased the small or half trade, on pain of four Flemish pounds each time.

7. Idem and in order to prevent cheating from now on certain sizes of panels shall be brought to the chamber of the said trade and kept there, viz. the following measures:

The measures which are named ordinarily as a dozen pieces121

of twenty-six stuivers

of guilders

of eight stuivers

of stooters

and of the half stooter.

8. All this in order to guarantee that all panels would be made at their firm and appropriate quality and measure.

9. Item it is ordered that the joiners shall not be allowed to set to work and employ the labourers [servants] of the panelmakers just as the panelmakers may not sub-hire and set to work the labourers of the joiners, on pain of twelve guiders each time.

10. Idem said joiners shall not [!] be allowed to make frames from beechwood, d but only the noses and inner frames on pain of six guilders and with regard to altar tables, e graves or similar large works they shall be required to make the same from good straight-grained 122<= radially cut] oak without inserting and using any beech or softwood, on pain of twelve guilders.

11. And because it will happen daily that through inspecting and branding of panels the deans or elders will often be inconvenienced and for reasons of what is prescribed have to leave their houses often, so, in consideration of this they shall be granted for the inspecting and branding of every dozen panels, from a measure of twenty-six stuivers to one guilder measure inclusive, two stuivers, and from the measure of eight stuivers or lower of every dozen panels, one stuiver. And in so far as someone wants to have only three, four or five panels visited, the same may carry them to the dean’s house to have them inspected there and [that] shall in such cases be allowed, at a cost proportional to the above.

Wishing and ordering expressly that each of the keepers and the deans of the joiners now and in the future be required and held to and observe this present ordonnance in all its points and clauses and to have them followed on each point on pain of the fines described above, subject to us and our successors in office being able always to add, take away, interpret, increase, decrease and change such things as shall seem to us or to them well-advised or appropriate. With no evil intent, in knowledge of the truth we, said Henrick van Varick have placed our own seal, and we above-mentioned burgomasters, alderman and council, have had the business seal of this city appended to this document in the year of our Lord, as written, one thousand six hundred and seventeen, 11 days into the month of December, and was signed: G.v. Wens.

Archive: SAA [Stadsarchief Antwerpen = City Archives of Antwerp] G & A [Gilden & Ambachten = Guilds and Trades fund], [no.] 4335, folios 78 verso – 81 recto

Notes on transcription: a. Sic – b. After having written the first two characters of the term, without striking those through. – c.Repeated: be. – d.Written in the brabantine form as ‘bueckenhout’. – e. Struck through: and.

[1] Also I hear that, in Antwerp and elsewhere, where the altars broken by the sectarians are, God being propitious to us, erected again, statues of the saints are more rarely placed in the altars: more often we find instead painted boards, and this for no other reason than that more artifice is said to lie in these paintings than in statues.

[2] J. Molanus, De historia SS. Imaginum et Picturum. Pro vero sarum usu contra abusus. Libra Quator, Leuven, 1594, published and annotated by J.N. Paquot, Leuven, 1771, p 203.

[3] J. Van Brabant, Rampspoed en restauratie. Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis van de uitrusting en restauratie der Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal van Antwerpen, Antwerpen, 1974, passim.

[4] P. Rombouts en Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, Antwerpen-Den Haag, 1872, dl.1, p 144, 154, 156, 181, 182, 199 and 226.

[5] To avoid any confusion, we have strictly maintained these different terms throughout the translation of this text.

[6] It being understood that no separate marks were in use for woodwork and polychroming. In normal circumstances the panels exhibit the mark of the fortress with hands as a quality mark for the wood.

[7] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, GA # 4336 and 4346.

[8] The equivalent document for the St Lucas Guild was, as far as is known to us, not kept. That of the joiners exists in several copies. Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, GA # 4003, f°88v-91r; GA # 4334, f°60v-62v, GA # 4335, f°78v-81v, GA # 4575, nr 6.

[9] The joiners were no members of the guild of St. Lucas, as claimed by M. Schuster-Gawlowska, “Marques de corporations, poinçons d’atelier et autres marques apposées sur les supports de bois des tableaux et des retables sculptés flamands. Essai de documentation à partir des collections polonaises”, in Jaarboek van het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, 1989, p 218.

[10] Antwerpsch archievenblad, 30th of January 1477, 1r, 20, p 51-52. The regulation was repeated on the 15th of June and the 23th of July 1478, 1r, 21, p 75-76 and p 80-81.

[11] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, GA # 4335, f° 1r-6v, art 21.

[12] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, GA # 4335, f° 14v-16r and GA # 4869, f° 11v-13v.

[13] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, PK # 710, f° 32.

[14] See footnote 8.

[15] F. Prims, “Het altaar van den Jongen Handboog”, in Antwerpiënsia. Losse bijdragen tot de Antwerpsche geschiedenis, 12, 1938 (1939), p 323; H. Vlieghe, “Het altaar van de Jonge Handboog in de O.-L.-Vrouwkerk te Antwerpen”, in Album Amicorum J.G. Van Gelder, Den Haag, 1973, p 342-350.

[16] F. Prims, “Het altaar der wijntaverniers”, ”, in Antwerpiënsia. Losse bijdragen tot de Antwerpsche geschiedenis, 13, 1939 (1940), p 427-433; J. Van Brabant, Rampspoed en restauratie, p 38.

[17] F. Prims, “Het altaar van de hoveniers”, ”, in Antwerpiënsia. Losse bijdragen tot de Antwerpsche geschiedenis, 13, 1939 (1940), p 337-343; C. Van De Velde, “De Aanbidding der Herders van Frans Floris”, in Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, 1961, p 69; J. Vervaet, “Catalogus van de altaarstukken uit de Onze-Lieve-Vrouwkerk te Antwerpen en bewaard in het Koninklijk Museum”, in Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, 1976, p 209-211.

[18] E. Geudens, Het hoofdambacht der meerseniers, 4, Antwerpen, 1904, p 86.

[19] Daniël Arents, joiner from Dendermonde, became citizen of Antwerp on the 26th of July 1577. Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, V # 151, sub dato; Mentioned as Danel Arons in P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl. 1, p 286.

[20] E. Poffe, De gilde der Antwerpsche schoolmeesters van bij haar ontstaan tot aan hare afschaffing, Antwerpen, 1895, p 22.

[21] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 1329, f° 11r-13r, 24-04-1572; CERT # 38, f° 13v, 27-09-1577; N # 528, f° 11r-13r, 1586.

[22] J. Van Damme, Otmaer van Ommen en zijn nageslacht (in preparation).

[23] J. Van Roey, “Het Antwerpse geslacht Van Haecht (Verhaecht). Tafereelmakers, schilders, kunsthandelaars”, in Miscellanea Jozef Duverger. Bijdragen tot de kunstgeschiedenis der Nederlanden, Gent, 1968, dl. 1, p 27.

[24] See below.

[25] Franchois Gast was tasked in 1566-67 as a joiner with removing the cannoners’ altar from the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw church, out of fear of the iconoclasts. F. Prims, “Het altaar der kolveniers”, in Antwerpiënsia. Losse bijdragen tot de Antwerpsche geschiedenis, 13, 1939 (1940), p 304. He many times held important posts in the joiners’ craft: dean from 1549 to 1552, elder in 1553 and ‘busmeester’ (treasurer) in 1547. Michel Gast supplied in 1588 a bench for the dockworkers’ and cordwainers’ in the same church. J. Van Damme, Bijdrage tot de studie van de Antwerpse schrijnwerkers, hun ambacht en hun werk tijdens het corporatief stelstel, unpublished licentiate’s thesis, Leuven, 1985, dl. 2, p 109; P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl. 1, p 128, 292, 306 and 341.

[26] The only case known to us is that of Lenaert Clinckenborch who in 1614 left two frames and two doors of a painting; E. Duverger, Antwerpsche kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw, 1600-1617, vol.1, p 313-314. In the same workshop was also the master’s examination work of his son Abraham, as a master in the joiners’ craft since 1608-09; Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3364; and also precisely in 1614 registered in the St Luke’s Guild as a joiner; P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, [IM, correction] dl.2, p 505, 508 and 513.

[27] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, GA # 4335, f° 83v-86v.

[28] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3364.

[29] [IM, new reference] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, 7 # 6931.

[30] They do appear in the administrative records of Jan II Moretus as dean of the guild in 1616-17. Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), Uitgaven van de Maatschappij der Antwerpsche bibliophilen, 1, Antwerpen, 1878.

[31] See the lists below under nos 1, 9, 89, 90, 171-181, 186 and 241 and E. Van Damme, De polychromie van gotische houtsculptuur in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden. Materialen en technieken, Verhandelingen van de Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van België, 44, 35, Brussel, 1982, p 170-171.

[32] A church interior in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels (inv. no. 4487), carries in the foreground on a clearly depicted gravestone the date 1613. In our view this is not a date for the painting itself but relates solely to the gravestone. In a similar way the inscription on a woman’s portrait attributed to Cornelis de Vos ‘Aetatis suae 57 anno 1613’ cannot be seen as the date of execution of the portrait. Finally, on closer inspection, it turned out that the signature 16MR16 (M. Rijckaert) on a panel from the Museum Bredius in The Hague is not original (See list of marked panels nos. 9, 122 and 125).

[33] Antoinette Wiael, the widow of Hans van Haecht, painter, tableau-maker and paintings merchant († 1621), visibly continued her husband’s business after his death. The inventory drawn up at her death (1627) mentions inter alia, eighty unfinished panels in eight-stuiver size and thirty-six unfinished frames of the same size. E. Duverger, Antwerpsche kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw, 1600-1617, vol.3, p 30-62.

[34] KASKA, Oud Archief St. Lucasgilde, 99 83* and 103 81*; [IM, new reference] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, 7 # 538, 1623-1628.

[35] Proof is this is, in at least one case, the letter A which can be found by radiography under the whitening layer. H. Von Sonnenburg, l.c.

[36] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, WK # 482, f° 59r-73v [REMARK by JVDPPP: WK#482 should be N#3492, [unpaged] 20-11-1614] and WK#688, f° 220r-313r.

[37] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3450, f° 116r-118v, 16-06-1616

[38] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 359; dl.2, p 89; Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives,WK # 688, f° 220r. (REMARK by JVDPPP: Extensive archival research has not led to the confirmation of Van Damme’s assumption that Artus and Michiel were brothers. Nor was it possible to determine another family relationship between the two.)

[39] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 515 and 523; Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), p 18 mentions correctly: Hans Claessens, panel maker, son of Machil: at Vleminckvelt (1616-17).

[40] Death duty registered in P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 588.

[41] In making this and the following lists we have been able to count on the willing cooperation of J. Wadum (Copenhagen) and many others, too many to name, who have pointed out to us marks known to them. Within the framework of this contribution it was not possible, however, to check the validity of all the data that they submitted and even less that of the many ascriptions. These lists are therefore intended solely as basic material for further research.

[42] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 255 and 562; Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3357, 29-03-1661 (will); N # 3492, 20-11-1614 (appraiser of the goods in the inventory of panel maker Michiel Claessens) and SR # 354, f° 494r, 1578; SR # 366, f° 369 and 735v, 1581; SR # 380, f° 64r, 1584; SR # 439, f° 167, 1600; SR # 447, f° 48, 1602; SR # 451, f° 27, 1603, N # 1173, f° 174, 1583 (transactions real estate).

[43] See footnote 23.

[44] P. Visschers, Iets over Jacob Jonghelinck, metaelgieter en penningsnijder, Octavio van Veen, schilder, in de XVIe eeuw; en de gebroeders Collyns de Nole, beeldhouwers, in de XVe, XVIe en XVIIe eeuw, Antwerpen, 1853, p 45 en 47; P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 332-333. It is not clear whether Hans van Haecht in 1616, for the high altar of Hoboken church, simply delivered a panel or whether in his capacity of art dealer also provided a painting. W. Van Bladel, Acht eeuwen geschiedenis van de parochie Hoboken en van de Zwarte God, Hoboken, 1980, p 87, 93 and 97.

[45] A. Monballieu, “P.P. Rubens en het “Nachtmael” voor St. Winoksbergen (1611), een niet-uitgevoerd schilderij van de meester”, in Jaarboek Koninklijk Musuem voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, 1965, p 18. See also E. Duverger and H. Vlieghe, David Teniers der Aeltere. Ein vergessener Flämischer Nachfolger Adam Elsheimers, Utrecht, 1971, note 67.

[46] See footnote 23.

[47] E. Duverger, Antwerpsche kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw, 1600-1617, vol.1, p 252, 385 and 482.

[48] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 409, 466 and 469.

[49] Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), p 24.

[50] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 245, 433, 445, 456, 457 and 486.

[51] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3372, sub dato; SR # …, f° 491r.

[52] R. Van Passen, Geschiedenis van Edegem, [IM, correction] Edegem, 1974, p 363-364.

[53] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, dl.2, p 117 and 122.

[54] List of marked panels, nos. 58-59.

[55] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.2, p 215 and 220.

[56] One such mark has been indicated to us. We lack, however, the necessary data to include it here.

[57] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 270, 326, 379 and 488.

[58] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 452, 493, 531 and 547.

[59] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 638.

[60] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 236. See also p 303 and 355 as glazier. Probably he was the son of carver Peeter Vernyen, see Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, PK # 2930, p 44, 1542.

[61] Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), p 22.

[62] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3379, 3-11-1625.

[63] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 498, 500 and 531.

[64] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 455.

[65] Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), p 17.

[66] E. Duverger, Antwerpsche kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw, 1600-1617, vol.1, p 267.

[67] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3365, 22-06-1611.

[68] R. MARIJNISSEN, Schilderijen. Echt-fraude-vals, Brussels-Amsterdam, 1987, p. 67 gives though an illustration of a mark consisting of the initials L and H.

[69] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 484 and 488-489.

[70] See footnote 36. [IM, correction] In neither of the documents mentioned in footnote 36 Guilliam Aertssen appeared as assessor in the workshop of Michiel Claessens in 1624.

The actual document where Guilliam Aertssen was mentioned as an assessor (together with Jacques Lutsens) is the inventory of Michiel Claessens made by the notary Bartholomeus Van den Berghe in 1614. Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3492, 1614.

[71] KASKA, Oud Archief St. Lucasgilde, 99 83* and 103 81*; [IM, new reference] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, 7 # 538, 1623-1628.

[72] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, PK # 2920, p 37. [IM, addition, Van Damme refers to the notes of De Burbure. The archival document De Burbure refers to is V # 156.] Guilliam Aertssen was referred to in the Vierschaarboek. This court dealt with criminal cases and various disputes between indiviuals. Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, V # 156, 1636-1654..

[73] Statement of J. Wadum, Kopenhagen.

[74] List of marked panels, no. 111.

[75] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 395, 401 and 599.

[76] [IM, new reference] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, 7 # 966.

[77] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3363, sub dato. He should not be confused with the carpenter Hans van Beemen. See Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3366, 9-3-1612.

[78] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3374, 20-05-1620; N # 3378, 1624.

[79] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3372, sub dato.

[80] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3378, 1624. He lived there already in 1616-17. Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), p 20.

[81] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, GA # 4338. As Hans Soeners, alias Vleennickx, son of master carpenter Adriaen van Herentals.

[82] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, Processen supplement, 1648. He declared on this occasion that he was 37 years old. In 1613 he asserted, however that he was 41 years old. Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, GA # 4339.

[83] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, WK # 567, f° 190r-208v. Inventory of decease dd May 1628.

[84] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3364. Hans Hoener’s servants (knechten) included Peeter van Herentals.

[85] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, PK # 1342, f° 113.

[86] See footnote 79.

[87] [IM, correction] Guilliam Gabron (1586-1674) is the son of Hans Gabron († between 1623 and 1627) and his first wife Catharina Vermeulen. See the record of his baptism in the State Archives of Belgium on http://www.arch.be. State Archives of Belgium, parish Antwerp Onze-Lieve-Vrouw, certificates of baptism, 1580-1592.

[88] M. Rooses, Geschiedenis van de Antwerpsche schilderschool, dl.2, Gent-Antwerpen, 1880, p 127-128.

[89] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 455, 531 and 559.

[90] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, WK # 482, f° 67.

[91] [IM, new reference] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, 7 # 6931.

[92] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 505, 509, 532 and 677; Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), p 56.

[93] The son of an existing master. The name derives from the custom of existing masters’ sons being excused the heavy master’s entrance fee in return for paying for the wine at the entrance feast.

[94] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 426.

[95] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, WK # 543, f° 446r-484v (inventory on decease).

[96] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 625.

[97] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, SR # 583, f° 150r-151r. Already in 1616-17, Philips lived in the St. Anthonisstraat. Boek gehouden door Jan Moretus II, als deken der St Lucasgide (1616-1617), p 20.

[98] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, WK # 932, f° 89r-102v.

[99] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, SR # 751, f° 399v-401r.

[100] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.2, p 268 and 293. See also Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 354, 1626 (will) and PK # 2924, p 60, 1643.

[101] List of marked panels, nos 132 and 134.

[102] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 273, 287, 303, 339, 368 and 448; E. Duverger, Antwerpsche kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw, 1600-1617, vol.1, p 83, 84 and 147; Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3369, 19-06-1615 and SR # 358, f° 31r, 1579.

[103] The last will and testament of Peeter Kerbos Peeterssone, then an invalid, was drawn up on that date. Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, N # 3511, sub dato. This means that it was not for Peeter I that death duty was paid in 1626-27 as suggested in the printed edition of the ‘Liggeren’. P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 638.

[104] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 385 and 399.

[105] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 625, 632 and 662.

[106] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 433, 505, 509 and 570.

[107] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, WK # 482, f° 1r-15v (inventory on decease dd. April 1621).

[108] A. Gepts, “Tafereelmaker Michiel Vriendt, leverancier van Rubens”, in Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, 1954-60, p 83-87; E. Duverger, “Vrindt Michiel”, in Nationaal biografisch woordenboek, 7, Brussel, 1977, kol. 1030-1036.

[109] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, WK # 695, f° 152r-167v (inventory on decease).

[110] See footnote 108; H. Leemans, De Sint-Gummaruskerk te Lier, Antwerpen-Utrecht, 1972, p 300.

[111] E. Duverger, “Vrindt Michiel”, in Nationaal biografisch woordenboek, 7, Brussel, 1977, kol. 1030-1036.

[112] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.1, p 426. Nicolaes is therefore not Michiel’s son, as maintained by M. Schuster-Gawlowska, “Marques de corporations, poinçons d’atelier et autres marques apposées sur les supports de bois des tableaux et des retables sculptés flamands. Essai de documentation à partir des collections polonaises”, in Jaarboek van het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, 1989, p 225, footnote 45.

[113] A. Monballieu, “Aantekeningen bij de schilderijeninventaris van het sterfhuis van Jan Snellinck”, in Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, 1976, p 253.

[114] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, PK # 2920, p 282.

[115] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, PK # 3066, p 22.

[116] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.2, p 456.

[117] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.2, p 544.

[118] P. Rombouts and Th. Van Lerius, De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche St. Lucasgilde, dl.2, p 611.

[119] KASKA, Oud Archief St. Lucasgilde, 99 83* and 103 81*; [IM, new reference] Felixarchief / Antwerp City Archives, 7 # 538, 1623-1628.

[120] The term “spiegelcassen” can also mean: mirror cabinets

[121] i.e. serial work.

[122] i.e. serial work.