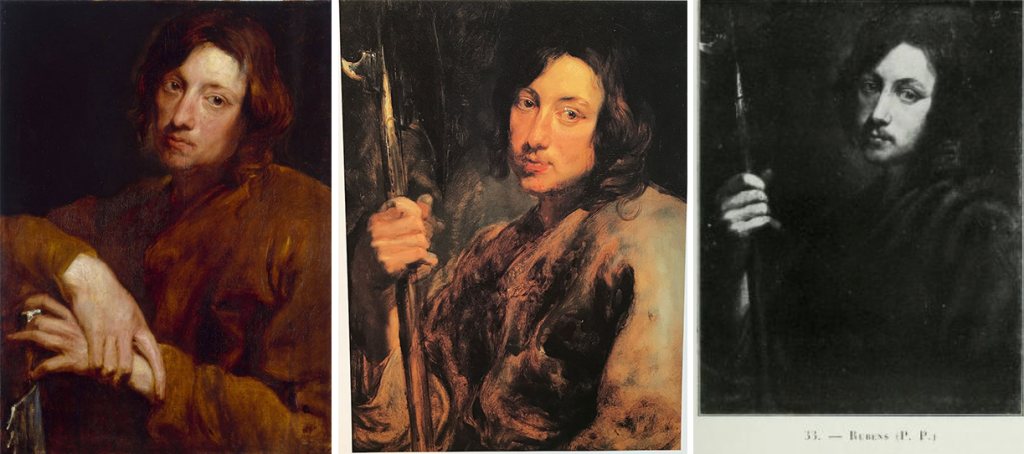

Almost 100 years later Gustav Glück’s ‘The Early Work of Van Dyck’ remains an important contribution to the art historical literature on Van Dyck. It was published in Vienna in 1924, at which time Glück (1871 – 1952) was the Director of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, a position he held from 1916 to 1931. It is a surprisingly difficult pamphlet to find and is now published online for the first time. Its online publication has allowed us to add images of 35 paintings cited by Glück, as opposed to the eight that were included in the original publication. Only two of the attributions since the publication of the 1924 article have changed and these changes are highlighted in the present text. The rare original copy used for this online edition is located in the library of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, NAL 33. NN Box III, by kind permission.

Justin Davies & James Innes-Mulraine

Editors’ notes: Revisions and updates, excepting minor grammatical or linguistic amendments, are contained in square brackets in the main body of the text, and also provided through the addition of endnotes. The paintings illustrated are published with their current locations.

The original text is available for download as a scanned document (PDF file).

How to cite: Glück, Gustav “The Early Work of Van Dyck” In Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project. Edited and updated, with an introduction, by Justin Davies and James Innes-Mulraine

http://jordaensvandyck.org/article/gustav-gluck-the-early-work-of-van-dyck/ (accessed 18 December 2025)

Gustav Glück, Anton Schroll and Co (Vienna), 1924,

edited and updated, with an introduction, by Justin Davies and James Innes-Mulraine (2019)

The artistic development of Anthony Van Dyck in his youth puts before us one of the most difficult, yet one of the most interesting problems. His early maturity is a phenomenon in the history of painting. We find him working independently at the age of sixteen;1 this does not however sound so very extraordinary, when we consider that, as a child of eleven, the artist became a pupil of Hendrik van Balen, a mannerist in the style of that period. The pictures, which this most highly gifted youth painted during the seven years, from 1615 to about 1622, differ so greatly, that they have been subject to various misinterpretations. Wilhelm Bode, with his incomparable gift of intuition, was the first, here as in many other cases, to discover the course which we should adopt in our researches. Bode was hardly ever mistaken in making an attribution, yet he was at first unable to do more than bring light into the matter in a general way. A more intimate perusal of the subject ought to give us a clearer insight into Van Dyck’s development in the first, and perhaps most important, period of his activity. It is essential for us to recognize that Van Dyck was no imitator but, from the very first, an artist with a strong personality, and a strong will of his own. He owed a great deal, perhaps most of his art, to Rubens, yet what Van Dyck gave to the world of art of his own accord is by no means as unimportant, as was generally supposed.

In face of the great number of Van Dyck’s works of these seven years, and of their great variety, it is no wonder that even experienced scholars have become confused. One of the most fatal errors, made in this respect, is the attribution to Van Dyck of a painting in the Galleria Corsini in Rome, a St Sebastian [fig. 1].

This theory, first proclaimed by Max Rooses (L’Oeuvre de Rubens, II, 1888, p. 350), was accepted by Emil Schaeffer (Klassiker der Kunst, XIII, 1909, p. 431) and finally upheld by as remarkable a scholar as Rudolf Oldenbourg (Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst, IX 1914/5, p. 234), whose premature death meant a great loss to history of Art. According to our personal opinion, we are in no way justified in placing this unusual painting in any relation to Van Dyck’s artistic development. The classical, eclectic spirit of this painting, especially of the chief figure (the “Herculean body” reminded even Oldenbourg of Rubens) is sufficient proof against the authorship of Van Dyck, and speaks strongly for that of Rubens. In spite of pronounced light and shade, the light coming from one side, the entire painting is kept in the rather light tones, characteristic for the manner of Rubens’ last years in Italy.

This is also true of the soft modelling of the figures (the angel at the right reminds us of the Susanna in the Galleria Borghese [fig. 2]), of the dark landscape with its blunt bluish-green, as well as of the customary representation of angels in various ages.

Oldenbourg is quite right in recognizing the breast-plate standing at the left of the Saint, as an implement from Rubens’ studio. Yet it is difficult to follow his argument, when he regards this as a counter proof against Rubens’ authorship. This breast-plate occurs in a painting, a St George, in the Prado in Madrid, which Oldenbourg himself (Klassiker der Kunst, V, 1921, 4th edition, p. 22) dates about 1607 to 1608, and which consequently must have been painted in Italy [fig. 3]; it recurs in the “Lion-Hunt” of the Munich Pinakothek [fig. 4] and in the “Erection of the Cross” in the Cathedral of Antwerp [fig. 5], compositions painted by Rubens after his return from Italy. Rubens may easily have brought this breast-plate home from Italy, for it is not likely that the master, who was then already a court painter, and generally had an apprentice to accompany him, should have travelled only with a portmanteau.

This breast-plate, studies of which may have existed, seems an undeniable proof of the authorship of Rubens, which is also evident from the style. We therefore adhere to the traditional opinion, accepted by Wilhelm Bode (in Burckhardt’s Cicerone), and Franz Martin Haberditzl (Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen, Vienna, XXX, 1912, p. 259) which has led us to place this painting chronologically among the pictures painted by Rubens in Italy (Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen, Vienna, XXXIII, 1915, p. 12).

The error of making Van Dyck responsible for this St. Sebastian is also emphasised by a comparison with the young artist’s authenticated paintings of the same subject. These are much further removed from the painting in the Corsini Gallery than the powerful, lonely figure in Rubens’ well-known picture in the Museum in Berlin [fig. 6].

There are two versions of St Sebastian by Van Dyck in the Pinakothek; the one, slightly larger, was probably painted after Van Dyck’s first and shorter Italian trip (about 1622-1623) [fig. 7]; 2 the other, was doubtless painted later, during his longer visit to Italy (about 1625) [fig. 8].3 [See the editorial endnotes regarding the present art historical opinion that Van Dyck left for in Italy in 1621 and did not return to Antwerp until 1627].

In both these compositions, Van Dyck tells the story from a new point of view. We see the preparations for the martyrdom of the Saint, who is still unhurt and being tied to a tree by soldiers. This interpretation of St. Sebastian might be described as a “languishing young martyr”; in contrast to the Rubens painting of the Corsini Gallery, where the nude figure with the huge body and a comparatively small head, appears strongly influenced by classical models. Another later painting by Van Dyck (about 1630) in the Eremitage at [Saint] Petersburg, (E. Schaeffer, as above, p.101) [fig. 9] depicts the Saint as an even more elegant figure.

The subject is the same as that of the painting in Rome, angels are freeing the Saint from his bonds and from the arrows, yet what a contrast between the sentimental pathos of the one, and the monumental force of the other picture. The painting in [Saint] Petersburg forms a bridge to a series of imitations – some coarse, some more insipid – which were productions of the later school of Rubens. They all describe the same subject; two angels ministering to the Saint. There are examples, wrongly under the name of Van Dyck, in the Louvre in Paris, (No. 1964, E. Schaeffer, as above, p. 99; by an artist like Jan Thomas) [fig. 10] [Ed. update: this painting is now given to Van Dyck, see S. J. Barnes et. al, Van Dyck, A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, Yale University Press, 2004, III. 52, pp. 286-7] and in the Parish Church at Schelle (E. Schaeffer, as above, p. 100; very closely related to Gillis Backereel, and with reason disputed by F. M. Haberditzl in Kunstgeschichtliche Anzeigen, 1909, p. 63) [fig. 11] [Ed. update: This painting is now given to Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert, see A. Heinrich, Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert (1613/14-1654), Ein Flämischer Nachfolger Van Dycks, Brepols, 2003, I, A. 33, pp. 197-9, II, Abb. 55, p. 522].

Strange to say there is another painting in a well-known gallery, under the right name – always in view, and yet unnoticed – which shows us how Van Dyck interpreted the legend of St. Sebastian at the very period into which Oldenbourg placed the Rubens painting, and before the origin of the famous series of the Apostles. This is a large canvas, not very well preserved, in the Louvre in Paris (No. 1981) [fig. 12]. The subject is identical with that of the two pictures in Munich. Yet there is a great difference in the style, the Paris painting being a much earlier work. It is impossible to doubt the authorship of Van Dyck. The composition is quite in the energetic, passionate manner of his early years. We see the Saint as a muscular youth, with strong, almost coarse forms, nude except for a white loin-cloth, leaning against the trunk of an oak. He is gazing at the spectator with a sad countenance. His right hand is already tied to the tree; his left hand, hanging down, is being entwined with ropes by an old man, who steps forward energetically. Behind this half naked old man, we see a thief catcher, looking at the Saint with wrathfully distorted features, and brandishing a pair of arrows in his hand. Further to the right, today greatly cut off by the edge of the frame, there is a soldier on a fine white horse. At the left, a fourth soldier is occupied with Sebastian’s clothes; beside him there is a very lively dog.

This painting, broad and almost sketchy in the handling, corresponds in various details with several known paintings of Van Dyck’s early period. The head of the Saint reminds us slightly of the young artist’s own features; it is even more like the head of a youth, which recurs in two series of Apostles, one in the Dresden Gallery as Simon [fig. 13], and another as Lord Spencer’s in Althorp as St. Matthew [fig. 14] (a copy of the latter was sold at the Sedelmeyer auction in Paris 1907, No.33) [fig. 15].

The wrathful soldier behind the old man appears as Judas Thaddeus in exactly the same pose, only looking upwards instead of sideways, in a painting in the Louvre (wrongly as St. Joseph; reproduced by E. Schaeffer, as above, p.5) [fig. 16].

Originally there must have been more of the beautiful white horse in the picture, a considerable strip of canvas having apparently been cut off at the right margin. There is a wonderful study for this horse in the Christ Church Library at Oxford (reproduced, Tancred Borenius’ Catalogue of this Collection, No.323) [fig. 17].

Finally, we find the same dog, as in the foreground, on the left of this painting, in the same attitude, in Van Dyck’s version of a St. Ambrose in the National Gallery in London; the latter must be a study for a large picture in the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum, also executed by Van Dyck [fig. 18].

We see how, in accordance with his usual habit, Van Dyck used studies for the St. Sebastian of the Louvre, which he had also used for others of his early works.

A considerable number of history paintings by the young Van Dyck are similar in the style to the St. Sebastian of the Louvre. We mention these in the probable sequence of their origin; a “Drunken Silenus” [fig. 19] and a “Crucifixion of St. Peter” [fig. 20] in the Museum at Brussels; a “Dead Christ” in the old Pinakothek in Munich [fig. 21] [Ed. update: this painting is now given to the Circle of Rubens, see M. Neumeister et al., exh. cat., Van Dyck, Gemälde von Anthonis van Dyck, Alte Pinakothek/Hirmer, 2019, p. 43, ill.], “Samson and Delila” in the Gallery of Dulwich [fig. 22], a “St. Jerome” in the Liechtenstein Gallery in the Vienna [fig. 23], “Christ carrying the cross” in the Church of St. Paul in Antwerp [fig. 24], and finally an “Entry of Christ into Jerusalem” at Mr. Rudolf Kohtz’ in Berlin (repr. By E. Schaeffer, as above, p.40) [fig. 25]. We know the last of these paintings from reproductions only.

In all these works, Van Dyck appears from a point of view quite foreign to the generally accepted opinion of his art. There is not a trace of the almost calligraphic elegance and the brilliant handling of his later paintings; yet there is also little, and only on the last-named paintings, of the energy and the determined manner of Rubens. Van Dyck’s paintings of this period, which we might call his uncouth or coarse style, are almost purely naturalistic. He is still far from the ideal of beauty, expressed in the noble heads and graceful figures of his later art; he does not avoid ugliness, if it helps to emphasize important characteristics. A careful study of nature is the young artist’s chief object. His figures are strong and muscular, almost clumsy; the hands, especially those of men, are fleshy and coarse; the types of the heads are broad, even square, generally not beautiful, but with marked features; the hair in streaks, as if it were damp. The landscapes are hardly more than broad, hasty sketches. A seemingly casual, quite unartificial, grouping of the figures brings out the naturalistic style of the composition. There is something unwieldy in the motions of the figures, which are often taking large strides, with their upper bodies leaning forward. The workmanship is broad and careless, the colouring light and clear, with a prevailance of a strong red. The contrasts of light and shade are not fully developed. Unlike the mannered style of those times, and of his first teacher, Van Dyck appears here as a realist, laying more stress on force then on beauty of form.

It is hard to say from where Van Dyck took this coarse style. Not from a mannerist like his first teacher, Hendrik van Balen. Nor can Rubens’ influence alone be the cause of this development. There is even a slight spirit of contradiction perceptible in his work, against the mannerists, as well as against the style of Rubens, who at that time was rather fond of idealisations. The young Van Dyck, whom history has been wont to describe as an imitator and follower, was aiming at an absolutely new style of his own. He was even ready to sacrifice a great deal that was pleasing to the eye, and to work in a manner opposed to the tastes of his public. He may have found some inspiration in the works of a group of artists, who had found their own style before Rubens’ return from Italy. These were the Naturalists, like Abraham Janssens, to name only one important representative; they saw the salvation of Netherlandish art in the following of Caravaggio, and were very late in acknowledging the supremacy of Rubens.

To these of Van Dyck’s paintings in his coarser style, we might add a “Crouching Satyr with a Flute”, in the Gallery of Count Nostitz in Prague, (No. 234; perhaps identical with “Een Sater met een fluyte, van Van Dyck”, in the estate of Jeremias Wildens 1653, Antwerpsch Archievenblad, XXI, p. 382), if the state of preservation of this painting permitted us to be positive of the authorship on Van Dyck.4 When we survey this group of paintings in the order in which we have mentioned them, we become aware of a very gradual evolution of the artist’s style. The influence of Rubens, at first scarcely noticeable, is quite clear only in the three last paintings; “Christ carrying the Cross” in the Church of St. Paul in Antwerp [fig. 24], “Samson and Delila” in Dulwich [fig. 22], and the “Entry into Jerusalem” at Mr. Kohtz’ in Berlin [fig. 25]. These paintings form a transition to the pictures painted in Rubens’s studio during the apprenticeship of Van Dyck, and during his collaboration on the large compositions of the head of this school.

It is most instructive to compare each of Van Dyck’s works of this period with his later versions of these same subjects. The first interpretation of a theme, which Van Dyck handled twice more later, is apparently the St. Jerome of the Liechtenstein Gallery in Vienna [fig. 23]. The manner of this work is powerful, yet purely realistic, without any great force of imagination. While the workmanship is hasty, it becomes attractive through the breadth of the handling. The Saint is depicted writing; his head is ugly, his body almost hunch-backed; the bright clear red of the cloak is the only correspondence of this canvas, painted in 1616, with the artist’s later versions. Far more profound in the whole conception is a “St. Jerome with an Angel holding his Pen”, in the Museum in Stockholm; the old man is lost in thought, the figures of the Saint and angel are more beautiful; the work is inspired by a strong ideal. This picture was authentically painted while Van Dyck was living in the house of Rubens and we can imagine that this was at a period, when the younger artist was collaborating on the monumental compositions of the master’s, in about 1618 [fig. 26].

A few years later comes the St. Jerome of the Dresden Gallery, in which an old man with a noble head and figure, is looking upwards with a rapt expression. In the harmony of the whole composition, in the emotional, almost sentimental pathos of the figure, in the broad treatment of the landscape and in the finely blended values, we clearly recognise the influence of the Italian, chiefly the Venetian school. Therefore, the origin of this painting must have been after Van Dyck’s presumable first trip to Italy, about 1622.5 There is a similar contrast between Van Dyck’s two versions of a “Drunken Silenus”. The first of these compositions, in the Museum at Brussels, with heavy clumsy forms, is almost coarse in the workmanship; the second, in the Gallery of Dresden, with more delicate figures – see the fine hands with long fingers – and a most exquisite colour-scheme, must likewise have been painted after the first Italian journey, about 1622-1623 [fig. 28].6

There is an even greater contrast between the St. Sebastian in the Louvre, which we have discussed at the outset, and the later versions of this subject in the Pinakothek in Munich. How graceful are the forms in the larger of the Munich canvases, painted about 1622-1623; what harmony in the composition, what profound sentiment in the expression, what depth and what softness in the values. The second of these paintings in the Pinakothek is similar to the Sebastian of the Louvre in the size, and in the quantity of figures; yet the manner of the painting is still further removed from the earlier work. We clearly recognise the style characteristic of Van Dyck’s second, long visit to Italy, and parallel to that of his Genoese portraits [fig. 29].7

In this same manner, there is a group of history paintings, which includes – to name only a few examples – a St. Magdalen in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam [fig. 30], the “Susanna” in the Munich Pinakothek [fig. 31], an “Incredulity of St. Thomas”, in the Eremitage in Petersburg [fig. 32], the “Four ages of Man” in the Museo Civico of Vicenza [fig. 33] , etc., and which culminates in a large altar-piece, the “Madonna of the Rosary” at Palermo [fig. 34].

To this group we must add another picture, which is of great interest to us, because it also represents a young saint. This is a St. John the Baptist, owned by William P. Fearon in New York [fig. 35]. A youth, almost naked, is seated in a landscape reading a book; the cross of twigs and the lamb at his feet are the characteristics of St. John the Baptist. The figure, with a dark red drapery covering the knees, stands out brilliantly from the powerful, sombre tones of the landscape, and the cloudy sky. The attitude of the figure, placed diagonally across the picture, gives great vivacity and force to this unusually charming composition. August L. Mayer called our attention to this painting, which was discovered by Mr Fearon. It is identical with a St. John the Baptist in the desert (“San Gio. Battista nel deserto”), described by Giovanni Pietro Bellori (Le Vite de Pittori, Scultori ed Architetti moderni, Rome 1728, p.157) as the property of Sir Kenelm Digby, who was a well-known personage at the court of Charles I of England, and whose portrait Van Dyck painted several times. This painting clearly shows the change which Van Dyck’s ideal of the young nude figure underwent, since the origin of the St. Sebastian of the Louvre. Unlike his former clumsy forms, we see the noble slender proportions, the long limbs and small heads, similar to the style of his Genoese portraits. There could be no greater contrast between two works by the same artist, and therefore we are forced to place the dates of these two paintings as far apart as possible. We are convinced that the St. John of Mr. Fearon’s was painted in Italy, about 1625. Perhaps Sir Kenelm Digby, then ambassador of the Queen of England at the court of Pope Urban VIII, brought this painting home to London, together with other pictures. There must have been a space of almost ten years, between the course, realistic St. Sebastian in the Louvre, painted not later than 1616, possibly even 1615, and this exquisite St. John, a painting already corresponding to the famous portraits painted by the master in Genoa.

1. The view that Van Dyck operated an independent studio from the age of 16 is now challenged. See Nora de Poorter in Susan J. Barnes, Nora De Poorter, Oliver Millar, Horst Vey, Van Dyck A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, Yale University Press, pp. 16, 67. Van Dyck was recorded as being a Master in the Guild of Saint Luke on 11 February 1618 age 18, see http://jordaensvandyck.org/archive/antonio-van-dyck-membership-fee-master-guild-11-february-1618/

2. Current art historical opinion is that a return by Van Dyck to Antwerp between 1621 and 1627 is unproven. Therefore, his Italian period is considered as 1621 to 1627. See Susan Barnes in Barnes et. al., op. cit., p. 145.

3. See endnote ii above regarding Van Dyck’s Italian period.

4. We have so far been unable to locate an image of this painting. It does not appear in either Emil Schaeffer, Klassiker der Kunst in Gesantausgaben, Dreizehnter Band, Van Dyck Des Meisters Gemälde in 537 Abbildungen, Stuttgart und Leipzig, 1909 nor Gustav Glück, Klassiker der Kunst in Gesantausgaben, Dreizehnter Band, Van Dyck Des Meisters Gemälde in 571 Abbildungen, Stuttgart und Berlin, 1931.

5. See endnote ii above regarding Van Dyck’s Italian period. The painting is currently considered to have been produced during Van Dyck’s first Antwerp period up to the latter months of 1621. See Barnes et. al, op. cit., no. I. 35, pp. 50-1, ill.

6. Also considered as first Antwerp period, ibid, no. I. 83, pp. 83-5, ill.

7. Also considered as first Antwerp period, ibid, no. I. 48, p. 65.